Nicholas of Cusa (Nikolaus Cryfftz or Krebs in German, then Nicolaus Cusanus in Latin, 1401-1464) “Christian Neoplatonic framework to construct his own synthesis of inherited ideas”.

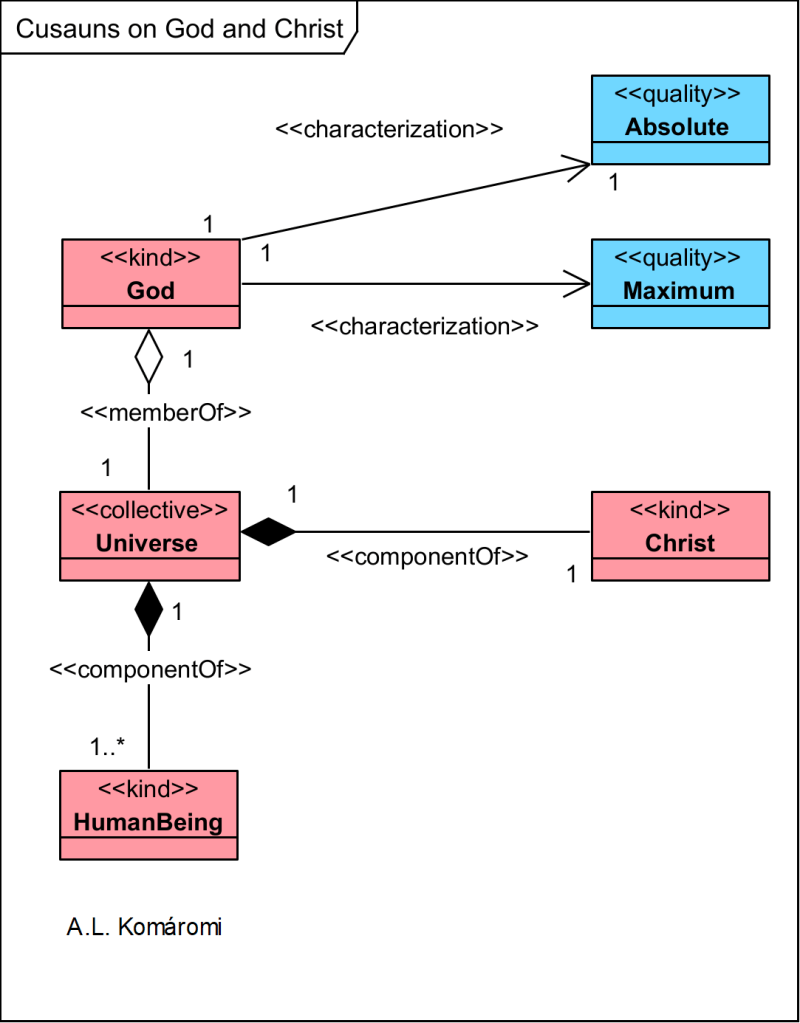

- Cusanus addresses the four categorical realities traditionally found in Christian thought: God, the natural universe, Christ and human beings.

- God is absolute and maximum.

The following OntoUML diagram shows Cusanus model of God:

| Class | Description | Relation |

|---|---|---|

| God | “Nicholas of Cusa’s most complete set of proposals about what is real occurs in his best-known work of 1440, De docta ignorantia: On Learned Ignorance. Here Cusanus addresses the four categorical realities traditionally found in Christian thought: God, the natural universe, Christ and human beings. […] Nicholas begins with a single trope or symbol to lay out the parallels between his teachings in the three books, that of the “maximum.” God is the absolute Maximum; the universe is a created image of God, the “contracted” or restricted maximum. […] “Absolute” is used in its etymological sense of “free from” (ab-solutus) to characterize God’s infinity. As absolute maximum God is both unlimited and transcendent, unreachable by human conceptions that measure the limited or contracted realm of more and less.” | |

| Absolute | “Absolute” is used in its etymological sense of “free from” (ab-solutus) to characterize God’s infinity. As absolute maximum God is both unlimited and transcendent, unreachable by human conceptions that measure the limited or contracted realm of more and less. Once Cusanus conceptualizes human knowing as measuring, he proposes that our knowledge also cannot measure exactly the essence of any limited thing. A fortiori, when it comes to the unlimited God, Nicholas asserts that “there is no proportion between finite and infinite.” The infinite God remains beyond our ken. Human efforts to understand the depth and implications of this assertion are what will render our ignorance “learn-ed.” | characterizes God |

| Maximum | “Nicholas begins with a single trope or symbol to lay out the parallels between his teachings in the three books, that of the “maximum.” God is the absolute Maximum; the universe is a created image of God, the “contracted” or restricted maximum.” | characterizes God |

| Universe | “Here Cusanus addresses the four categorical realities traditionally found in Christian thought: God, the natural universe, Christ and human beings.” | member of God |

| Christ | “Here Cusanus addresses the four categorical realities traditionally found in Christian thought: God, the natural universe, Christ and human beings. […] God is the absolute Maximum; the universe is a created image of God, the “contracted” or restricted maximum. Christ unites the first two as the Maximum at once absolute-and-contracted.” | component of Universe |

| HumanBeing | “Here Cusanus addresses the four categorical realities traditionally found in Christian thought: God, the natural universe, Christ and human beings.” | component of Universe |

Sources

- Miller, Clyde Lee, “Cusanus, Nicolaus [Nicolas of Cusa]“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 2023/2/28