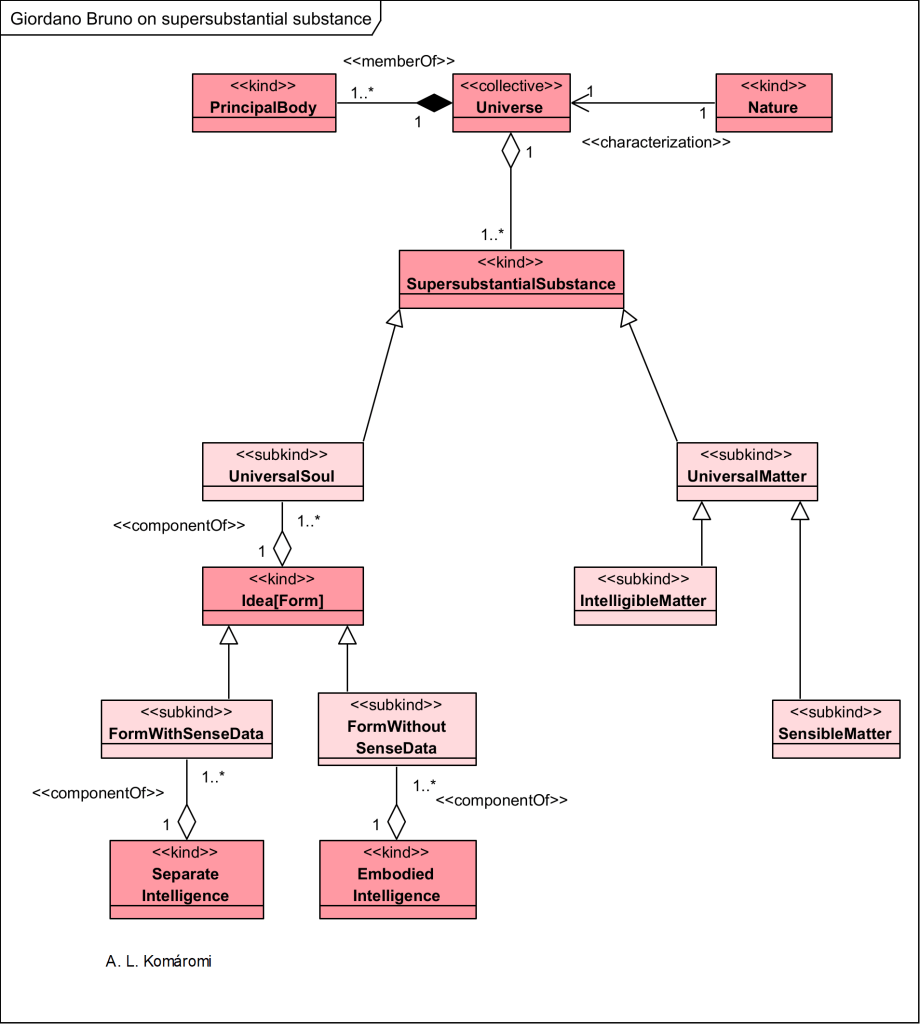

Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) analyzed the structure of the relation between the universal soul and universal matter existing in the realm of universal (principal) bodies:

- Principal bodies are members of the Universe, characterized by nature.

- The Universe aggregates supersubstantial substance.

- Supersubstantial substance can universal soul and universal matter.

- Intelligible matter and sensible matter are subkinds of supersubstantial substance.

- Idea[Form] is component of the universal soul, and has form with sense data and form without sense data as subkinds.

- Form with sense data is component of the separate intelligence.

- Form without sense data is component of the embodied intelligence.

The following OntoUML diagram shows Bruno’s model of the universal soul and universal matter.

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | “Bruno’s Platonic interpretation of God’s exitus accounts for his celebrated dictum “Nature is God in things” (BOI II, 354; BOL I.2, 151; I.4, 101). Nicholas of Cusa probably inspired the formula. In a work that Bruno knew, Nicholas identified Plato’s World Soul with Aristotle’s concept of Nature, before concluding that “the World Soul or Nature was no less than God operating in all things” (The Layman: On the Mind, XIII.145). Bruno’s comments on God and Nature independently of the dictum agree with this sense. “God determined and ordered; Nature executed and produced” (BOL I.3, 136; similarly BOI II, 660). Nature was the Universal Soul/Intellect acting as the efficient cause (see Section 4) “within natural things” (BOI I, 598; BOL II.2, 176). It was the act of generation that “divided” matter (BOI II, 147), operating within it non-discursively, unlike art, as Ficino (Platonic Theology, IV.1) had observed, which operated discursively on material from without (BOI I, 680–682: BOL I.2, 312). The idea that plants and animals were the “living effects of Nature”, that “Nature was God in things”, had led the ancient Egyptians to worship images of the gods in the form of animals. Each living thing, in addition to its intrinsic being, incorporated something divine from the gods “according to its capacity and measure” (BOI II, 354–355). The “Egyptian” inspiration for Bruno’s comments in this instance was a passage in Ficino’s paraphrase of On the Mysteries of the Egyptians (VII.1-3) in which Iamblichus distinguished God as the cause of generation, Nature, from God in himself “ | characterizes Universe |

| Universe | “The universe was an organism in which principal body each and the life sustained on it participated in a common animating principle, in the same way as the many parts of the human body were vivified by one and the same soul. […] The Universal Intellect was, however, simultaneously separate from the corruptible things that it engendered in that it was immutable. Spatial language—“above”, “within”, “separate” and so forth—was, as Bruno recognized, inappropriate when describing intelligible realities. By definition, something intelligible had no location or dimensions. To clarify what he meant by the immanent and transcendent roles of the Universal Soul and its faculty, the Universal Intellect, Bruno appropriated a distinction formulated in Thomas Aquinas’s On the Principles of Nature. Principles were constituents of something. The marble of the statue and its form were constituents; hence, they were principles, the marble being the material, the form the formal principle. Causes, by contrast, were extrinsic. A sculptor was the efficient cause of a statue, and he made it with an end, a final cause, in mind. Neither the sculptor nor his purpose were constituents of the finished piece. Analogously the Universal Soul and Universal Matter were the two principles immanent in all things, whereas the Universal Intellect was the efficient cause of all things and so extrinsic to them. It also operated in accordance with a final and therefore extrinsic cause: the perfection of the universe“ | |

| PrincipalBody | “The universe was an organism in which each principal body and the life sustained on it participated in a common animating principle, in the same way as the many parts of the human body were vivified by one and the same soul. Even supposedly inanimate things had a vestigial presence of life. Rocks, for example, were alive to the same degree as the bones or teeth of animals were.” | member of Universe |

| SupersubstantialSubstance | “The two substances, Universal Soul and Universal Matter, were not antagonistic, Manichean. Though opposites, they were aspects of one and “the same principle” (BOI I, 698; BOL I.2, 344) or “supersubstantial substance” (BOI I, 557). Since this supersubstantial substance reconciled these and indeed all other opposites, it was a “plenitude” without a counterpart “non-being” (BOL III, 40). To explain its unity, Bruno turned to Nicholas of Cusa’s doctrine of the “coincidence of opposites”. Universal Matter and Universal Soul/Intellect coincided in an undifferentiated unity just as the circumference of an infinite circle and an infinite straight line, though distinct entities, coincided. Not for nothing did Bruno acknowledge that Nicholas’s doctrine had provided him with the means for reviving the ancient philosophy that had long been “defunct” (BOL I.3, 272). This supersubstantial principle was the God of whom the Egyptians Hermes and Moses had spoken. During his trial Bruno asserted that God had created all things from the two principles, “the World Soul and prime matter”, from which all things derive. “They depend with respect to their whole being on God, and they are eternal” (Firpo 2000, 381 [doc. 51, §252]). In his written works, too, he identified them with, respectively, the primordial darkness and light described in the first three verses of Genesis (BOL II.3, 117). This was not as provocative as it might seem. Origen, St Augustine and many other theologians had identified God’s first two creations on the First Day, “heaven” and “earth”, with, respectively, intellective beings—the angels—and matter.” | |

| UniversalSoul | “The Universal Soul [Universal Intellect] was “all-in-all”, that is, present wholly and indivisibly in each and every thing to the degree that it was capable of receiving it, just as, to borrow Plotinus’s analogy (Enneads,VI.4.12), a single voice was audible to everyone in a room, however great the audience. Bruno, like others before him, attributed the doctrine of “all-in-all”, in a dematerialized version, to Anaxagoras. He also adduced several scriptural witnesses, notably the Book of Wisdom (1:7), thereby identifying the Universal Soul implicitly with the Holy Spirit: “For the Spirit of the Lord filleth the world: and that which containeth all things hath knowledge of the voice”. No matter that the Council of Sens (1140) had anathematized this association.[..] Some philosophers, noted Bruno, called this space or container “vacuum” (BOI II, 160–161). All Universal Matter was “accompanied” by form, that is, the Universal Soul (BOI I, 665–666). This simple picture was complicated by Bruno’s interpretation of the Universal or, synonymously, First Intellect. Like the Neoplatonic Intellect, Bruno’s Universal Intellect comprised the Ideas; but, unlike its Neoplatonic counterpart, it was not a hypostasis distinct from, and ontologically prior to, the Universal Soul. Instead, it was “the inner and most essential and characteristic faculty” of the Universal Soul, operating immanently from within Universal Matter like “an internal craftsman” (BOI I, 652–654; BOL I.2, 312–313, 426; I.4, 107).” | subkind of SupersubstantialSubstance |

| UniversalMatter | “The Universal Soul combined with Universal Matter to produce the universe; the former was the active power, form, and the latter its passive subject. Bruno conceived Universal Matter as indeterminate space, that is, the receptacle of Plato’s Timaeus (52A–B) or more exactly Aristotle’s interpretation of it (Physics, IV.2, 209b6–17; IV.6, 214a12–19). In this respect, it was the motionless aether or spirit, devoid of any “specific quality” of its own (BOI II, 159–160; BOL I.2 78–79), that served as the medium through which soul acted on the two corporeal principles, earth atoms and water […] Universal Matter was present in incorporeal as well as corporeal things. It was the genus of two types of matter, corporeal and intelligible. The former was the substrate of corporeal objects, as described above. The latter, Plotinus’s version of Plato’s Indefinite Dyad as reported by Aristotle, was instead the substrate—the principle of indeterminacy or potentiality—of intelligible realities.” | subkind of SupersubstantialSubstance |

| Idea[Form] | “Bruno’s Universal Intellect [Universal Intellect] comprised the Ideas;” | component of UniversalSoul |

| FormWithSenseData | “Form with sensed data: forms that conserve and perfect themselves by desiring and apprehending unity by using sense data (e.g., cosmic, demonic, human, animal souls); together with sensible matter; these forms constitute” | subkind of Idea |

| FormWithoutSenseData | “Form without sense data: forms that conserve and perfect themselves by desiring and apprehending unity without using sense data (e.g. forms of stones, drops of water); together with sensible matter; these forms constitute” | subkind of Idea |

| SepatateIntelligence | “To explain how God, in his external aspect, articulated these differentiations, Bruno used Platonic concepts and themes. Ficino’s Christian Platonism was especially influential. God was a unity or undifferentiated plenitude of Ideas existing in him virtually. In this sense he was Mind. Dependent on him as Mind were: (a) the discrete Ideas unified in the Universal Intellect [Universal Intellect](see Section 4); and (b) the vestiges of the Ideas, that is, forms, which, in combination with sensible matter, produced corporeal things. Further, as Mind, he was also the supersubstantial principle of intelligence, contemplating the undifferentiated plenitude of Ideas within him in one timeless act. Dependent on him in this respect were intelligences of various kinds: (a) the Universal Intellect, which contemplated the discrete Ideas simultaneously as a unity; (b) disembodied intelligences, known conventionally as “separate intelligences”, which contemplated just one Idea absolutely; (c) embodied intelligences, a category that included the “principal bodies”, which, though embodied, contemplated God intellectively without the use of sense data and ratiocination, demons and human beings, both of whom used sense data and reason to attain intellection, and all other animals, even the simplest. Proof of this were animal instincts, as Ficino, too, had noted. Instincts were the presence of God as Mind working within them rather than, as scholastics typically held, powers that the stars instilled in them extraneously. Bruno’s next step was Presocratic rather than Platonic. All cognitive acts, in whatever animal or indeed separate intelligence, were instantiations of a single cognitive power deriving from the Universal Intellect and ultimately, therefore, from God as Mind” | component of FormWithSenseData |

| EmbodiedIntelligence | “(c) embodied intelligences, a category that included the “principal bodies”, which, though embodied, contemplated God intellectively without the use of sense data and ratiocination, demons and human beings, both of whom used sense data and reason to attain intellection, and all other animals, even the simplest. Proof of this were animal instincts, as Ficino, too, had noted. Instincts were the presence of God as Mind working within them rather than, as scholastics typically held, powers that the stars instilled in them extraneously. Bruno’s next step was Presocratic rather than Platonic. All cognitive acts, in whatever animal or indeed separate intelligence, were instantiations of a single cognitive power deriving from the Universal Intellect and ultimately, therefore, from God” | component of FormWithoutSenseData |

| IntelligibleMatter | “Universal Matter was present in incorporeal as well as corporeal things. It was the genus of two types of matter, corporeal and intelligible. Universal Matter was present in incorporeal as well as corporeal things. It was the genus of two types of matter, corporeal and intelligible. The former was the substrate of corporeal objects, as described above. The latter, Plotinus’s version of Plato’s Indefinite Dyad as reported by Aristotle, was instead the substrate—the principle of indeterminacy or potentiality—of intelligible realities. Bruno quoted two of Plotinus’s arguments for the existence of intelligible matter. First, the plurality of Ideas in the Intellect presupposed something common to each of them, this commonality being intelligible matter. Second, since the sensible world imitated the intelligible world and the sensible world comprised matter, so too must the intelligible. Plotinus, like other ancient Neoplatonists, considered the two matters ontologically distinct, as Bruno noted. Intelligible matter, as the matter of unchanging intelligible realities, did not change, Plotinus had explained. It “possessed” all things simultaneously. By contrast, the matter of sensible things possessed all things only inasmuch as parts of it assumed all possible forms sequentially. Bruno added a differentiation of his own, applying again Nicholas of Cusa’s distinction between explication and implication: intelligible matter was informed but unexplicated, sensible matter was informed but explicated. Nevertheless, Bruno insisted that corporeal and intelligible matter were, ultimately, two species of the genus Universal Matter. He was not the first to do so. The eleventh-century Jewish philosopher, Ibn Gabirol or, in Latinized form, Avicebron, as Bruno mentioned, had made the same move. Just as importantly, even if Bruno did not say so, so too had Ficino in accordance with Augustine’s Plotinian exegesis of Genesis 1:1–3. All distinctions, Bruno concluded, presupposed something indefinite: potentiality, matter. Hence the distinction between the two matters presupposed an absolute Universal Matter. No doubt he knew of Thomas Aquinas’s objections. Avicebron was wrong, Thomas had written, to say that species were the actualization of a genus’s potentialities and so attribute existence to what was a purely theoretical relationship between genus and species. Like Avicebron, Bruno sometimes went as far as to elevate Universal Matter above Universal Form. Nothing was “constant, fixed, eternal and worthy of being esteemed a principle apart from [Universal] Matter” (BOI I, 686). Form, that is, the Universal Soul, was “under the constant control of [Universal] Matter” (BOI I, 722). Its stability, which contrasted so favorably with the flux of form, had led the heterodox scholastic philosopher David of Dinant (d. 1215) “who had been poorly understood by some” to call matter “divine” (BOI I, 601, 723; BOL III, 695–696). Divine though it might be, Bruno did not identify Universal Matter with God. Indeed, he criticized Avicebron, misrepresenting him on the by, for having held that matter alone was “stable”, “eternal” and hence “divine” and for vilifying all substantial form, including the Universal Soul, as “corruptible” and ephemeral (BOI I, 687, 696). For Bruno, the Universal Soul was “mutable”, rather than “corruptible”, in relation to Universal Matter and only in this sense inferior to it (ibid.)e former was the substrate of corporeal objects, as described above. The latter, Plotinus’s version of Plato’s Indefinite Dyad as reported by Aristotle, was instead the substrate—the principle of indeterminacy or potentiality—of intelligible realities. Bruno quoted two of Plotinus’s arguments for the existence of intelligible matter. First, the plurality of Ideas in the Intellect presupposed something common to each of them, this commonality being intelligible matter. Second, since the sensible world imitated the intelligible world and the sensible world comprised matter, so too must the intelligible. Plotinus, like other ancient Neoplatonists, considered the two matters ontologically distinct, as Bruno noted. Intelligible matter, as the matter of unchanging intelligible realities, did not change, Plotinus had explained. It “possessed” all things simultaneously. By contrast, the matter of sensible things possessed all things only inasmuch as parts of it assumed all possible forms sequentially. Bruno added a differentiation of his own, applying again Nicholas of Cusa’s distinction between explication and implication: intelligible matter was informed but unexplicated, sensible matter was informed but explicated. Nevertheless, Bruno insisted that corporeal and intelligible matter were, ultimately, two species of the genus Universal Matter. He was not the first to do so. The eleventh-century Jewish philosopher, Ibn Gabirol or, in Latinized form, Avicebron, as Bruno mentioned, had made the same move. Just as importantly, even if Bruno did not say so, so too had Ficino in accordance with Augustine’s Plotinian exegesis of Genesis 1:1–3. All distinctions, Bruno concluded, presupposed something indefinite: potentiality, matter. Hence the distinction between the two matters presupposed an absolute Universal Matter. No doubt he knew of Thomas Aquinas’s objections. Avicebron was wrong, Thomas had written, to say that species were the actualization of a genus’s potentialities and so attribute existence to what was a purely theoretical relationship between genus and species. Like Avicebron, Bruno sometimes went as far as to elevate Universal Matter above Universal Form. Nothing was “constant, fixed, eternal and worthy of being esteemed a principle apart from [Universal] Matter” (BOI I, 686). Form, that is, the Universal Soul, was “under the constant control of [Universal] Matter” (BOI I, 722). Its stability, which contrasted so favorably with the flux of form, had led the heterodox scholastic philosopher David of Dinant (d. 1215) “who had been poorly understood by some” to call matter “divine” (BOI I, 601, 723; BOL III, 695–696). Divine though it might be, Bruno did not identify Universal Matter with God. Indeed, he criticized Avicebron, misrepresenting him on the by, for having held that matter alone was “stable”, “eternal” and hence “divine” and for vilifying all substantial form, including the Universal Soul, as “corruptible” and ephemeral (BOI I, 687, 696). For Bruno, the Universal Soul was “mutable”, rather than “corruptible”, in relation to Universal Matter and only in this sense inferior to it (ibid.)” | subkind of UniversalMatter |

| SensibleMatter | “By contrast, the matter of sensible things possessed all things only inasmuch as parts of it assumed all possible forms sequentially. Bruno added a differentiation of his own, applying again Nicholas of Cusa’s distinction between explication and implication: intelligible matter was informed but unexplicated, sensible matter was informed but explicated. Nevertheless, Bruno insisted that corporeal and intelligible matter were, ultimately, two species of the genus Universal Matter.” | UniversalMatter |

Sources

- Knox, Dilwyn, “Giordano Bruno“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 2023/2/28