Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry, the Phoenician (234?–305? BC) in his work Isagoge commented on Aristotle’s Categories (see [1.3.2]), where:

- he listed the predicables (universals) as genus, species, difference, property, and accidents

- and raised (but did not answer) paradigmatic questions about universals: “I shall abstain from deeper enquiries and aim, as appropriate, at the simpler ones. For example, I shall beg off saying anything about (a) whether genera and species are real or are situated in bare thoughts alone, (b) whether as real they are bodies or incorporeals, and (c) whether they are separated or in sensibles and have their reality in connection with them.” (Porphyry, Isagoge, in Spade 1994)

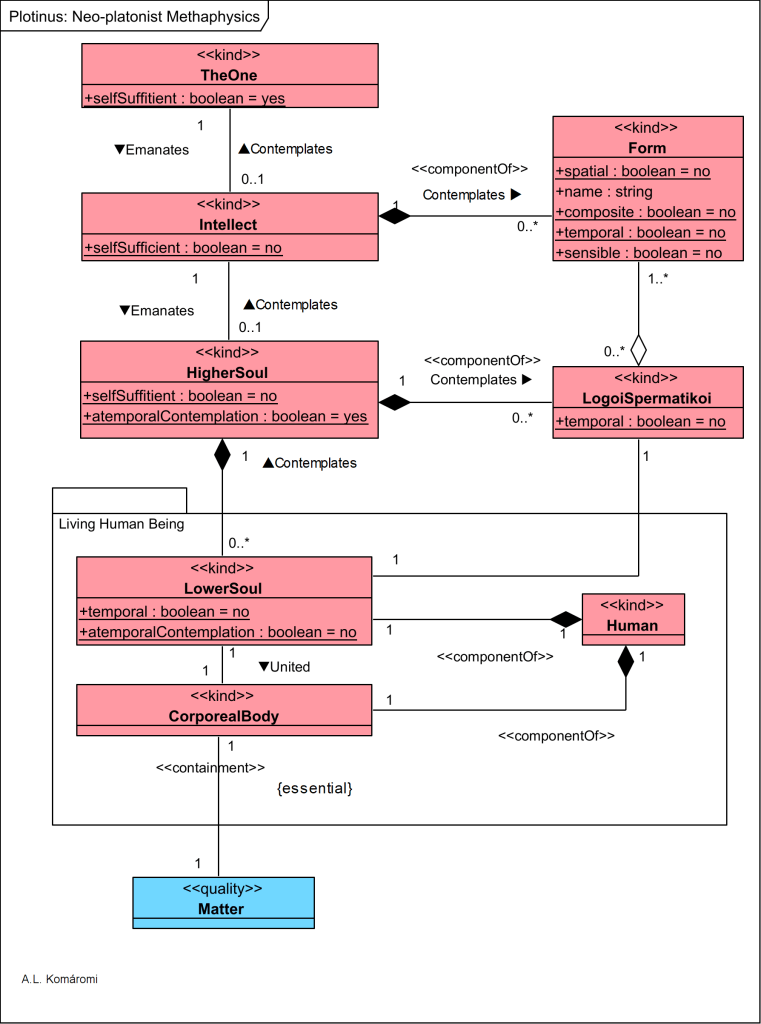

Porphyry’s model of universals is in the following OntoUML diagram:

| Description/Packag | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Predicables (Universals) | Porphyry “proceeds not by talking about the ten Aristotelian categories directly, but instead by discussing five words or notions that he says are important for a clear understanding of the Categories. These five notions are: genus, difference, species, property and accident. They came to be known as the five “predicables” — praedicabilia, not to be confused with the predicaments, which are the ten Aristotelian categories. Although there is considerable doubt about it, people sometimes say that Porphyry’s list of five predicables is based on a similar list of four items that Aristotle presents in his Topics I.4 101b23–25, and again in more detail in Topics I.5 101b37–102b26. There Aristotle discusses: definition, property, genus and accident. Porphyry’s list differs from Aristotle’s by adding difference, which Aristotle doesn’t have on his list, and by substituting species for definition.” | |

| Genus | “The genus is the part of the real definition that answers the broad question What is it? What is man? Man is an animal. Now in Latin, the interrogative pronoun ‘What?’ is ‘quid’. And so the genus of a thing is said to be predicated “in quid” of that thing. The phrase ‘in quid’ is a kind of horribly abbreviated way of saying “with respect to what the thing is,” or “in a way that answers the question ‘What is it’” — or in effect, “in a way that gives you the genus.” | is in a recursive association with itself; each level splits the superior level in 2 or more, based on the attributes marked in Difference |

| Difference | “On the other hand, the difference is the part of the real definition that answers the question What kind of a _ is it?, where the pause is filled in with the genus. What is man? Man is an animal. What kind of animal? A rational one. In Latin, the interrogative pronoun ‘What kind of?’ or ‘What manner of?’ is ‘quale’. And so the difference of a thing is said to be predicated of it not in quid, but rather in quale.” | defines Species; |

| Species | “Man is a most specific species. Below man there are only individual men, not yet lower species. What this means, of course, is that the differences among individual men are not essential differences but accidental ones. If they were essential differences, then we would have lower species after all.” | relates to itself recursively |

| Property | “In Aristotle and in Porphyry, and in medieval metaphysical discussions generally, the word ‘property’ means, first of all, something that is not essential to a thing (genus, difference and species are the essential predicables), but that nevertheless belongs to it and to it alone. (So exclusive ownership is only part of the story.) Now we’re not talking primarily about individuals here. In fact, Porphyry has very little to say about individuals at all in the Isagoge. We’re talking at the level of genera and species. And when we say something is a property of a certain species, we mean that it belongs to exactly the things in that species, and to nothing else. So we say, for instance, that it is a property of the species man to be risible — that is, to have the ability to laugh.” | characterizes Species |

| Accident | “the differences among individuals are accidental ones, not essential ones. […] Accident is what comes and goes without the destruction of the substrate.” | characterizes Individual |

| Individual | “Below man [as species] there are only individual men, not yet lower species. What this means, of course, is that the differences among individual men are not essential differences but accidental ones.” | subkind of Species |

Related posts in theory of Universals: [1.2.1], [1.3.1], [1.3.2], [2.5], [2.7.3], [4.3.1], [4.3.2], [4.4.1], [4.5.2], [4.9.8]

Sources

- All citations from: Spade, Paul Vincent, “History of the Problem of Universals in the Middle Ages”, Indiana University 2009

- Emilsson, Eyjólfur, “Porphyry”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Adamson, Peter,“92 – King of Animals: Porphyry”, History of Philosophy without any Gaps podcast

First published: 28/05/2020