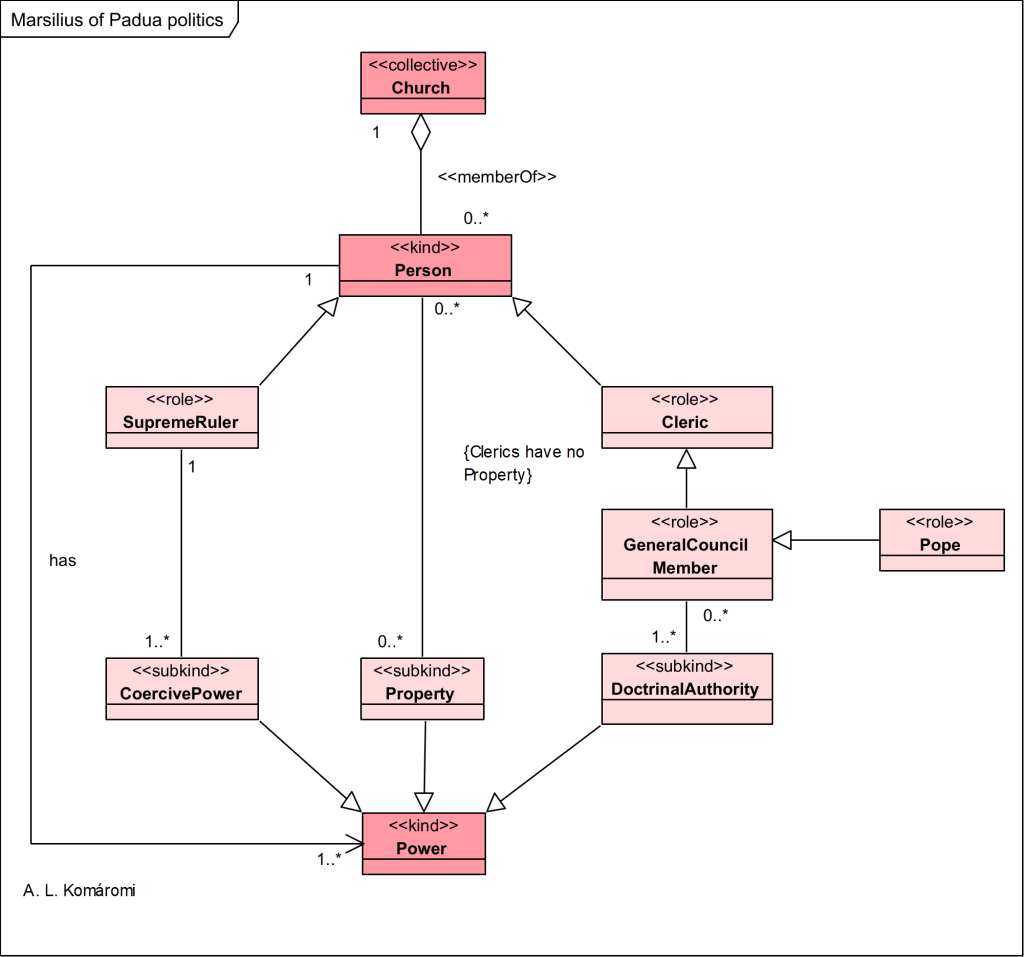

Marsilius of Padua (1243? – 1316) in the work Defensor pacis (1324) rejected the doctrine of absolute papal power of Boniface VIII. sustained by Giles of Rome. He thinks that:

- There is one and only one supreme ruler who holds all coercive power in a community.

- “The supreme ruler cannot be a cleric, since Christ has forbidden the clergy to become involved in temporal affairs (113–40/159–92). And the supreme ruler does not enforce divine law as such, since God wills that divine law should be enforced by sanctions only in the next world, to give every opportunity for repentance before death (164, 175–9/221, 235–9).”

- Clerics, members of the general council, and the Pope all have doctrinal authority.

- All people have the right to ownership and property except Clerics.

- Coercive power, doctrinal authority, and property are subkinds of power.

See also Giles of Rome on Papal Power.

The following OntoUML diagram explains the view Marsilius of Padua power:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Church | The church has members. | |

| Person | A human person | member of Church; has Power |

| SupremeRuler | “He argues that all coercive power comes from the people (44–9, 61–3/65–72, 88–90), and that no people can have more than one supreme ruler, who is the source of all coercive power in that community (80–6/114–22). The supreme ruler cannot be a cleric, since Christ has forbidden the clergy to become involved in temporal affairs (113–40/159–92). And the supreme ruler does not enforce divine law as such, since God wills that divine law should be enforced by sanctions only in the next world, to give every opportunity for repentance before death (164, 175–9/221, 235–9). The supreme ruler is therefore not an enforcer of religion and his rule is not subject to direction by the clergy.” | role of Person |

| Cleric | “the pope has from Christ no more authority than any other cleric“ | role of Person |

| GeneralCouncilMember | “Marsilius did believe that the Church exercised some authority over its members, but, so far as this was a doctrinal authority, it was exercised not by the pope but by a general council member (Marsilius held that the Bible and general councils are infallible, but not the pope (274–9/360–66)).” | role of General Council Member |

| Pope | “Within the Church, the Pope has from Christ no more authority than any other cleric. Christ did not appoint Peter as head of the Church, Peter never went to Rome, the bishop of Rome is not Peter’s successor as head of the Church (pp. 44–9/61–3)” | role of Pope |

| CoercivePower | “He argues that all coercive power comes from the people (44–9, 61–3/65–72, 88–90), and that no people can have more than one supreme ruler, who is the source of all coercive power in that community (80–6/114–22).” | subkind of Power |

| DoctrinalAuthority | “Marsilius did believe that the Church exercised some authority over its members, but, so far as this was a doctrinal authority, it was exercised not by the pope but by a general council (Marsilius held that the Bible and general councils are infallible, but not the pope (274–9/360–66)). Now that Europe is Christian a general council cannot be convened or its decisions enforced except by the Christian lay ruler (287–98/376–90).” | subkind of Power |

| Property | All people have the right to ownership and property except Clerics. “As for religious poverty, Marsilius sides with the Franciscans and takes their doctrine further: not only is it legitimate for religious to live entirely without ownership of property (they can use what they need with the owner’s permission), but this is what Christ intended for all the clergy (183–4, 196–215/244–6, 262–86). Thus on his view the pope and clergy should have no lordship at all, either in the sense of coercive jurisdiction or in the sense of ownership of property. His position is diametrically opposite that of Giles of Rome.” | subkind of Power |

| Power | Power |

Sources

- All citations from: Kilcullen, John and Jonathan Robinson, “Medieval Political Philosophy“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 4/4/2022