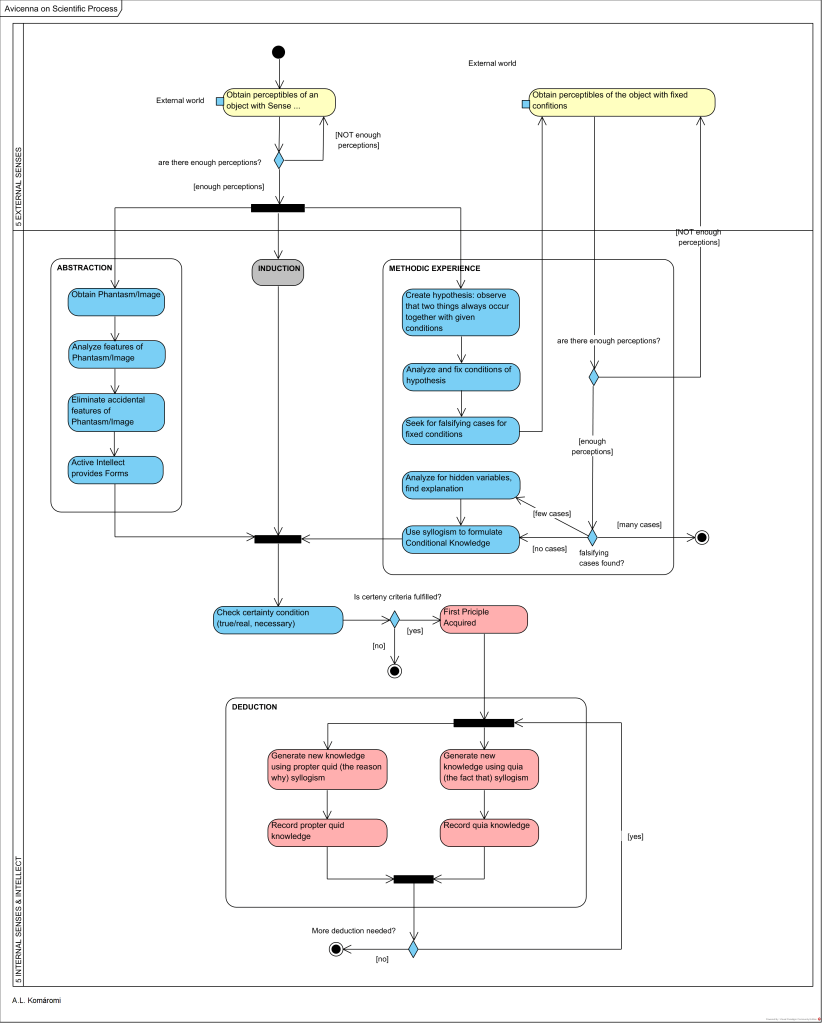

In the UML Activity Diagram below, I propose a reconstruction of the scientific “business” process based on Ibn Sina’s (Avicenna, 980-1037 AD) ideas about scientific inquiry elaborated in his works Kitāb al-Burhân, Najâh.

Here are some highlights of his ideas:

- Sense perception with the involvement of the 5 external and internal senses (see [3.3.3]) is the starting point of the scientific process.

- Abstraction, Induction and Methodic Experience are the activities to acquire First Principles. Syllogisms (see [3.3.5]) and actualization of the Intellect with Forms provided by First Intellect (see [3.3.3], [3.3.4]) both have their roles in these activities.

- After First Principles are available, new knowledge can be reached with deduction, using syllogisms (see [3.3.5]).

| ACTIVITY/Action | Description |

| Obtain perceptibles of an object with Sense Perception | “the universal premises of demonstration and their principles are obtained only through sensory perception…” (McGinnis (2008), cites Avicenna) |

| ABSTRACTION | “by acquiring the phantasmata (خيالات) of the singular terms through the intermediacy of [sensory perception] in order that the intellectual faculty freely acts on them in such a way that it leads to acquiring the universals as singular terms and combining them into a well-formed statement… [T]he essences perceptible in existence are not in themselves intelligible, but perceptible; however, the intellect makes them so as to be intelligible, because it abstracts their true nature (حقيقتها) from the concomitants of matter… Thus [the speculative intellect] receives these accidents, but then it extracts them, as if it is peeling away these accidents and setting them to one side, until it arrives at the account in which are common and in which there is no variation and so acquires knowledge of them and conceptualizes them. The first thing that [the intellect] inquires into is the confused mixture in the phantasm; for it finds accidental and essential features, and among the accidents those which are necessary and those which are not. It then isolates one account after another of the numerous ones mixed together in the phantasm, following them along to the essence. (McGinnis (2008), cites Avicenna) “this is not Avicenna’s whole story concerning abstraction and acquiring first principles; for as he says later, acquisition of the first principles also involves “a conjunction of the intellect with a light emanated upon the soul and nature from the agent that is called the ‘Active Intellect’” (McGinnis (2008)). |

| INDUCTION | Avicenna accepts Aristotle’s view on Induction (see [1.3.8]) however, criticizes it: “Induction has two elements: one involves the sensible content of induction and the other the rational structure of induction, namely, the syllogism associated with induction. If induction is to provide one with the necessary and certain first principles of a science, then the necessity and certainty of the conclusion of an inductive syllogism must be due either to induction’s sensory element or its rational element or some combination of both. On the one hand, the purported necessity and certainty of induction cannot be known solely through induction’s sensory element; for in good empirical fashion Avicenna recognizes that necessity and certainty are not direct objects of sensation. On the other hand, if the necessity and certainty are due to induction’s rational component, then the syllogism associated with induction should not be question begging. Yet, complains Avicenna, in the scientifically interesting cases one of the premises of an induction will be better known than its conclusion, and so the induction is neither informative nor capable of making clear a first principle of a science.” (McGinnis (2008)). |

| METHODIC EXPERIENCE | “Ibn Sînâ’s theory of experimentation is by no means modern, it does move one closer to a modern scientific approach; for it emphasizes both the need to set out carefully the conditions under which experimentation or examination have taken place, as well as the tentativeness of scientific discoveries in the face of new observations… experimentation involves in part seeking falsifying cases…the exceptions [falsifying cases] would be extremely rare, perhaps observed only once or twice. These rare exceptions might indicate that there is not a causal relation, but they might also indicate that the causal circumstances were more complex than initially supposed… Experimentation, with its accompanying syllogism, then, occasions certainty… although experimentation cannot provide “absolute” principles, the natural scientist can use experimentation to discover “conditional,” universal principles, which can function as first principles in a science.” (McGinnis (2003)). |

| Check certainty condition (true/ real, necessary) | “Avicenna’s ‘certainty condition’ (يقين),… includes both being true or real (الحقّ) and necessary (الضروري)” (McGinnis (2008)). |

| First Priciple Acquired | If certainty condition is fulfilled. |

| DEDUCTION | “A demonstration according to Avicenna is ‘a syllogism constituting certainty’. In other words, it is a deduction beginning with premises that are certain or necessary that concludes that not only such and such is the case, but that such and such cannot not be the case. Thus, demonstrative knowledge involves possessing a syllogism that makes clear the necessity or inevitableness obtaining between the subject and predicate terms of its conclusion. In addition, Avicenna divides demonstrative knowledge itself into two categories depending upon the type of demonstration employed. Thus there is the demonstration propter quid, or demonstration giving ‘the reason why’ ( برهان لِمَ ) and the demonstration quia, or demonstration giving ‘the fact that’ (برهان لأن ).” (McGinnis (2008)). |

Sources

- McGinnis, Jon, “Avicenna’s Naturalized Epistemology and Scientific Method”, chapter from: The Unity of Science in the Arabic Tradition: Science, Logic, Epistemology and their Interactions, springer, 2008

- McGinnis, Jon, “Scientific Methodologies in Medieval Islam”, Journal of the History of Philosophy. 41. 307-327. 10.1353/hph.2003.0033., 2003

First published: 05/09/2019