William Ockham (1285-1349 AD), in the treatise On the Connection of the Virtues and other works, elaborates a will-based ethics, where acts of will (intentions), and not actions have ethical value:

- Human beings have a natural tendency to achieve their ultimate good, like at Aristotle [1.3.17] and Augustine [2.6.5]

- The human will creates acts of will (intentions), which on their turn initiate ethically neutral actions. Acts of will can be virtuous and evil.

- Virtuous acts of will manifest moral virtue, and are subordinated to the ultimate good. Ockham “measures” moral virtue in a five-grade scale. Even pagans can have moral virtue, howeve that is not enough for salvation.

- Despite the human inclination towards the ultimate good, the human will is free to deliberately go against the zltimate good, and the choose evil. This theory antagonizes with the view on the limitations of the will held by Aquinas [4.9.9], [4.9.13].

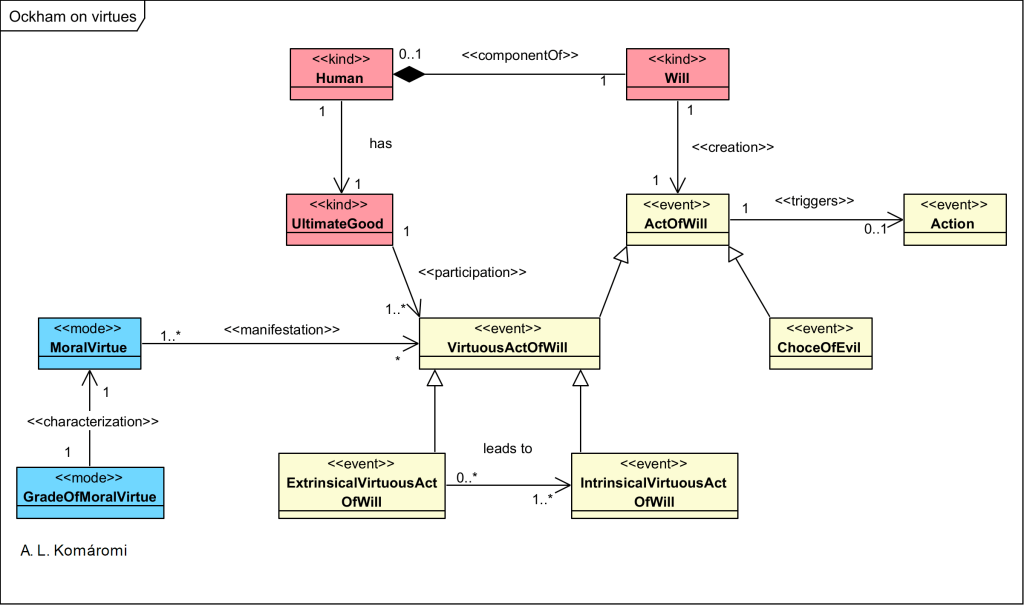

The following OntoUML diagram presents Ockhams’s model of virtues and free will:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Human | A human person | has UltimateGood |

| UltimateGood | “Ockham [..] is very suspicious of the notion of final causality (teleology) in general, he thinks it is quite appropriate for intelligent, voluntary agents such as human beings. Thus the frequent charge that Ockham severs ethics from metaphysics by denying teleology seems wrong. Nevertheless, while Ockham grants that human beings have a natural orientation, a tendency toward their own ultimate good, he does not think this restricts their choices.” | participates in VirtuousActOfWill |

| Will | “Ockham’s ethics combines a number of themes. For one, it is a will-based ethics in which intentions [will] count for everything and external behavior or actions count for nothing. In themselves, all actions are morally neutral.” | component of Human; creates ActOfWill |

| ActOfWill | For Ockham, acts of will are morally virtuous either extrinsically, i.e. derivatively, through their conformity to some more fundamental act of will, or intrinsically. On pain of infinite regress, therefore, extrinsically virtuous acts of will must ultimately lead back to an intrinsically virtuous act of will. That intrinsically virtuous act of will, for Ockham, is an act of “loving God above all else and for his own sake.” | ActOfWill initiates Action |

| Action | “In themselves, all actions are morally neutral.” | |

| VirtuousActOfWill | “For Ockham, acts of will are morally virtuous [virtuous act of will] either extrinsically, i.e. derivatively, through their conformity to some more fundamental act of will, or intrinsically.” | inherits from ActOfWill |

| ExtrinsicalVirtuousActOfWill | “On pain of infinite regress, therefore, extrinsically virtuous acts of will must ultimately lead back to an intrinsically virtuous act of will. ” | inherits from VirtuousActOfWill; leads to IntrinsicalVirtuousActOfWill |

| IntrinsicalVirtuousActOfWill | “That intrinsically virtuous act of will, for Ockham, is an act of ‘loving God above all else and for his own sake.’“ | inherits from VirtuousActOfWill |

| MoralVirtue | “moral virtue is possible even for the pagan, moral virtue is not by itself enough for salvation. In short, there is no necessary connection between virtue—moral goodness—and salvation. Ockham repeatedly emphasizes that ‘God is a debtor to no one‘; he does not owe us anything, no matter what we do.” | manifests in VirtuousActOfWill |

| GradeOfMoralVirtue | In his early work, On the Connection of the Virtues, Ockham distinguishes five grades or stages of moral virtue, which have been the topic of considerable speculation in the secondary literature: 1/ The first and lowest stage is found when someone wills to act in accordance with “right reason”—i.e., because it is “the right thing to do.” 2/ The second stage adds moral “seriousness” to the picture. The agent is willing to act in accordance with right reason even in the face of contrary considerations, even—if necessary—at the cost of death. 3/ The third stage adds a certain exclusivity to the motivation; one wills to act in this way only because right reason requires it. It is not enough to will to act in accordance with right reason, even heroically, if one does so on the basis of extraneous, non-moral motives. 4/ At the fourth stage of moral virtue, one wills to act in this way “precisely for the love of God.” This stage “alone is the true and perfect moral virtue of which the Saints speak.” 5/ The fifth and final stage can be built immediately on either the third or the fourth stage; thus one can have the fifth without the fourth stage. The fifth stage adds an element of extraordinary moral heroism that goes beyond even the “seriousness” of stage two. | characterizes MoralVirtue |

| ChoiceOfEvil | “For Ockham, as for Aristotle and Aquinas, I can choose the means to achieve my ultimate good. But in addition, for Ockham unlike Aristotle and Aquinas, I can choose whether to will that ultimate good. The natural orientation and tendency toward that good is built in; I cannot do anything about that. But I can choose whether or not to to act to achieve that good. I might choose, for example, to do nothing at all, and I might choose this knowing full well what I am doing. But more: I can choose to act knowingly directly against my ultimate good, to thwart it. I can choose evil as evil. [choice of evil]“ | inherits from ActOfWill |

Sources:

- All citations from: Spade, Paul Vincent and Claude Panaccio, “William of Ockham”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 13/1/2022