Epicurus (341-271 BC) establishes the goal of living is happiness, defined on two levels, (closely interrelated with his psychology [2.1.1] and physics [2.1.2]):

- happiness is a static pleasure on the level of sensations (perception)

- happiness is a lack of perturbation on the level of the state of mind.

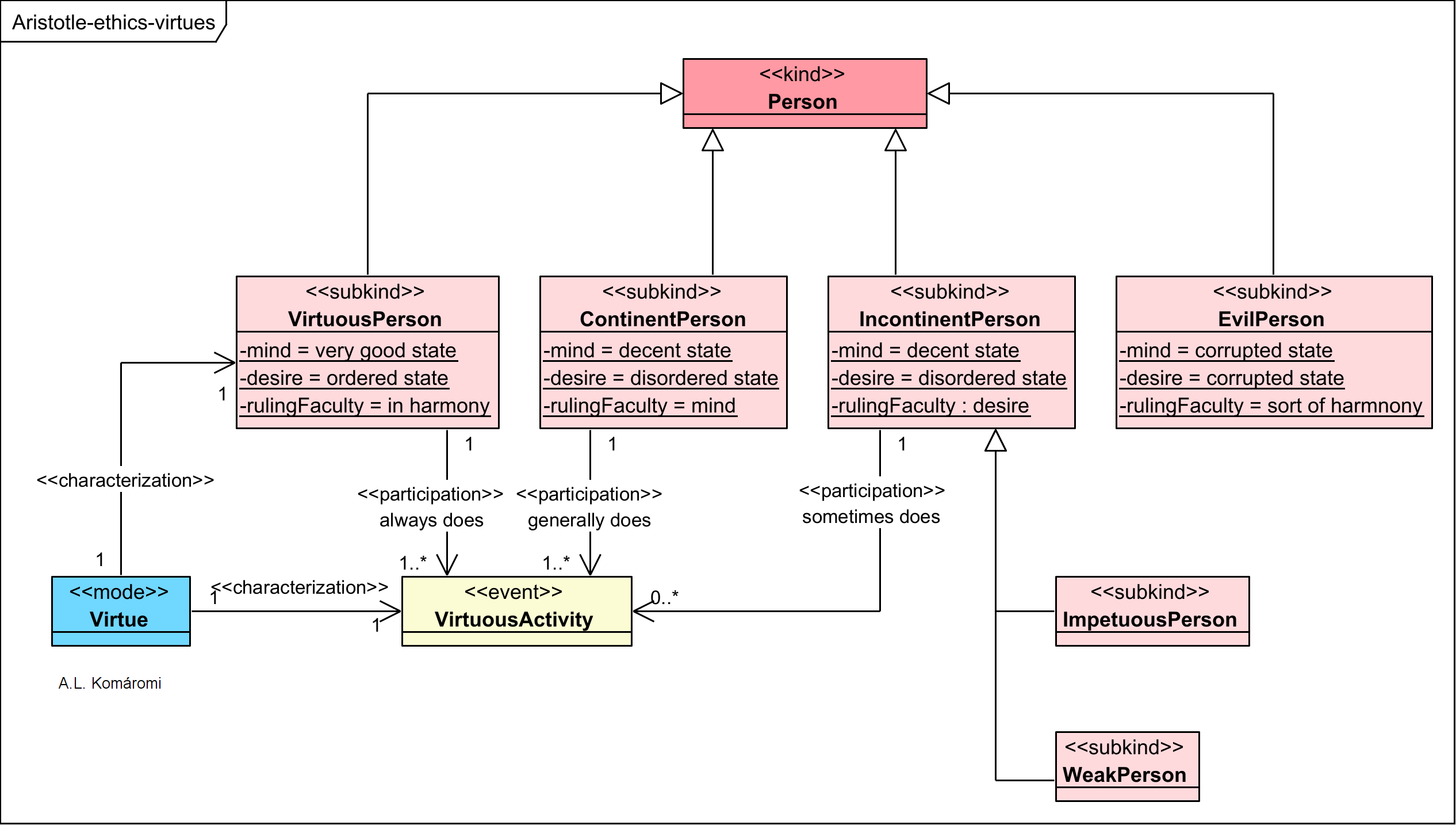

The OntoUML diagram below presents the main concepts of Epicurean ethics:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Person | A human person has a goal of living. | has GoalOfLiving; experiences PhysicalSensation; has StetOfMind |

| GoalOfLiving | The unique goal in life happiness. | is Happiness |

| Hapiness | Epicurus “the unique goal in life happiness based on freedom from physical pain and mental anxiety” [lack of perturbation] and enjoyment of static pleasure. | is StaticPleasure and LackOfPerturbation |

| PhysicalSensation | “Epicurus, it appears, uses the terms pleasure and pain (hêdonê, algêdôn) strictly in reference to physical pathê or sensations, that is, those that are experienced via the non-rational soul that is distributed throughout the body… soul atoms are particularly fine and are distributed throughout the body, and it is by means of them that we have sensations (aisthêseis) and the experience of pain and pleasure…” | |

| Pleasure | “The elementary sensations of pleasure and pain, accordingly, rather than abstract moral principles or abstract concepts of goodness or badness, are the fundamental guides to what is good and bad, since all sentient creatures are naturally attracted to the one and repelled by the other.” | is PhysicalSensation |

| StaticPleasure | “happiness (eudaimonia), according to Epicurus, is not simply a neutral or privative condition but rather a form of pleasure in its own right — what Epicurus called catastematic or (following Cicero’s Latin translation) ‘static’ as opposed to ‘kinetic’ pleasure…” Static “(catastematic) pleasure… is (or is taken in) a state rather than a process: it is the pleasure that accompanies well-being as such. The Cyrenaics and others, such as Cicero, maintained, in turn, that this condition is not pleasurable but rather neutral — neither pleasurable nor painful.” | is Pleasure |

| KineticPleasure | “kinetic pleasures seem to be of the non-necessary kind, such as those resulting from agreeable odors or sounds, rather than deriving from replenishment, as in the case of hunger or thirst… Epicurus objected that such pleasures are necessarily accompanied by distress, for they depend upon a lack that is painful… In addition, augmenting desires tends to intensify rather than reduce the mental agitation (a distressful state of mind) that Epicurean philosophy sought to eliminate.” | is Pleasure |

| Pain | Pain is an elementary sensation. | is PhysicalSensation |

| StateOfMind | state of mind | |

| LackOfPerturbation | The absence of fear is ataraxy, lack of perturbation. | is StateOfMind |

| Perturbation | “fear is one source of perturbation (tarakhê), and is a worse curse than physical pain itself” | is StateOfMind |

| Fear | “Most prominent among the negative mental states is fear, above all the fear of unreal dangers, such as death. Death, Epicurus insists, is nothing to us, since while we exist, our death is not, and when our death occurs, we do not exist; but if one is frightened by the empty name of death, the fear will persist since we must all eventually die.” | is StateOfMind; causes Perturbation |

| Joy | “There are also positive states of mind, which Epicurus identifies by the special term khara (joy), as opposed to hêdonê (pleasure, i.e., physical pleasure).” | is StateOfMind |

Sources

- All citations from: Konstan, David, “Epicurus”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 12/12/2019