Aristotle (384-322 BC) in Nicomachean Ethics and Eudemian Ethics sustains that ethics is not a theoretical discipline, but a practical science (see [1.3.10]), with the following main rules:

- happiness consists of practical, virtuous activity (not virtue, pleasure, knowledge)

- things such as health, wealth, pleasure are not the real goals of an accomplished person, but promote happiness

- virtue is a state of the soul and mind (see [1.3.6]), characterized by the lack of extremes (golden mean).

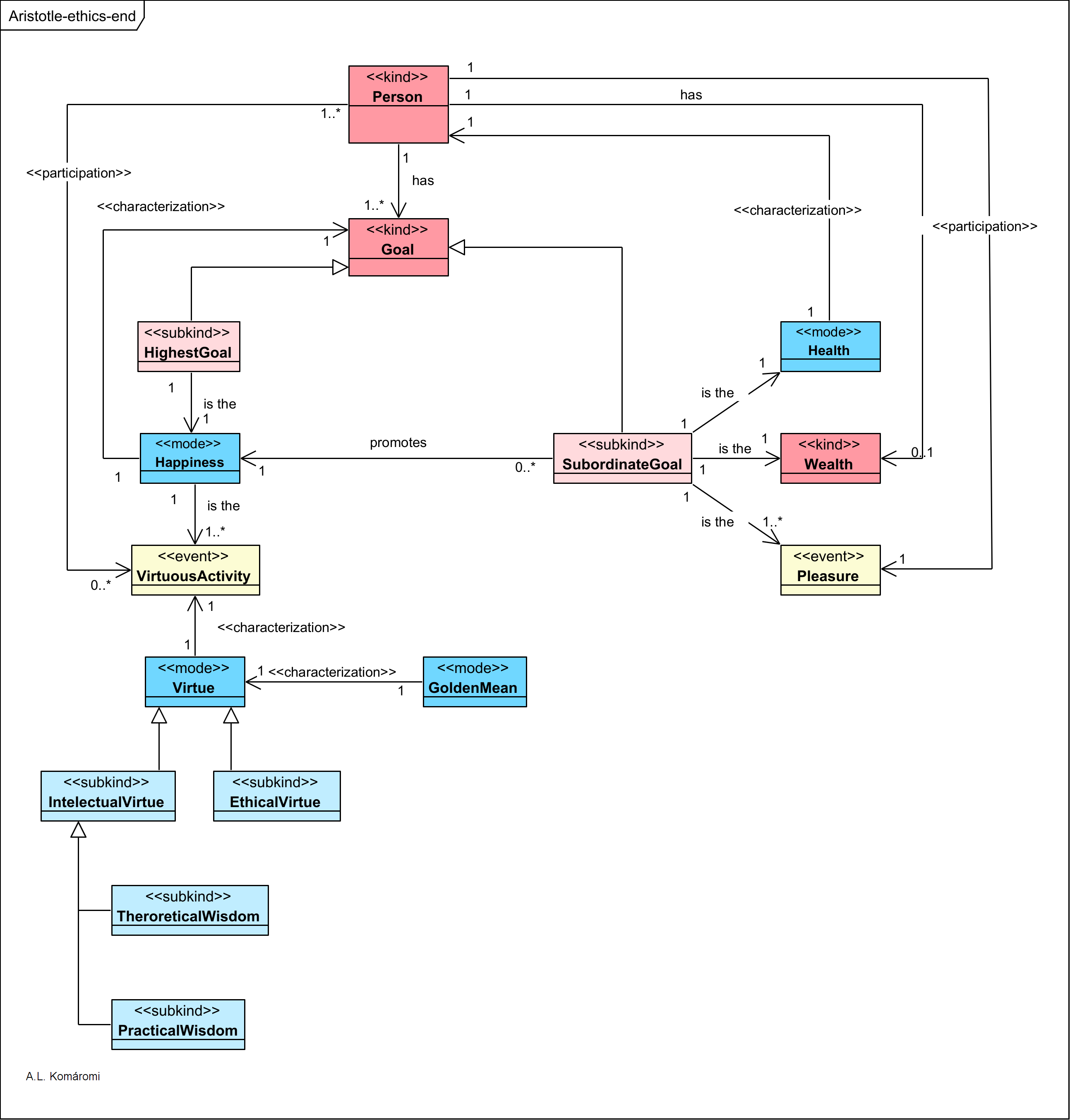

The OntoUML diagram below presents the main concepts of Aristotelian ethics:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Person | A human person has a goal(s). | has Goal; participates in VirtuousActivity; has Wealth; participates in Pleasure |

| Goal | Goal of a human person. | |

| HighestGoal | “Aristotle’s search for the good is a search for the highest good [goal], and he assumes that the highest good, whatever it turns out to be, has three characteristics: it is desirable for itself, it is not desirable for the sake of some other good, and all other goods are desirable for its sake.” | subkind of Goal; the Happiness |

| Happiness | “Aristotle thinks everyone will agree that the terms ‘eudaimonia‘ (‘happiness‘) and ‘eu zên‘ (‘living well’) designate such an [highest] end… He regards ‘eudaimon‘ as a mere substitute for eu zên (‘living well’).” | is the VirtuousActivity; characterizes Goal |

| SubordinateGoal | “all subordinate goals… are sought because they promote well-being, not because they are what well-being consists in… Aristotle makes it clear that in order to be happy one must possess others goods as well—such goods as friends, wealth, and power. And one’s happiness is endangered if one is severely lacking in certain advantages—if, for example, one is extremely ugly, or has lost children or good friends through death.” | subkind of Goal; promotes Hapiness; is the Health, Wealth and Pleasure |

| Health | Health promotes Happiness. | characterizes Person |

| Wealth | Wealth promotes Happiness. | |

| Pleasure | “Aristotle holds that a happy life must include pleasure, and he therefore opposes those who argue that pleasure is by its nature bad. He insists that there are other pleasures besides those of the senses, and that the best pleasures are the ones experienced by virtuous people who have sufficient resources for excellent activity. | |

| VirtuousActivity | “Aristotle asks what the ergon (“function”, “task”, “work”) of a human being is, and argues that it consists in activity of the rational part of the soul in accordance with virtue [virtuous activity]… The good of a human being must have something to do with being human; and what sets humanity off from other species, giving us the potential to live a better life, is our capacity to guide ourselves by using reason. If we use reason well, we live well as human beings; or, to be more precise, using reason well over the course of a full life is what happiness consists in. Doing anything well requires virtue or excellence, and therefore living well consists in activities caused by the rational soul in accordance with virtue or excellence… Living well consists in doing something, not just being in a certain state or condition. It consists in those lifelong activities that actualize the virtues of the rational part of the soul. (see [3.4])“ | |

| Virtue | Aristotle distinguishes two kinds of virtue: “those that pertain to the part of the soul that engages in reasoning (virtues of mind or intellect), and those that pertain to the part of the soul that cannot itself reason but is nonetheless capable of following reason (ethical virtues, virtues of character).” | characterizes VirtuousActivity |

| GoldenMean | “every ethical virtue is a condition intermediate (a “golden mean” as it is popularly known) between two other states, one involving excess, and the other deficiency. In this respect, Aristotle says, the virtues are no different from technical skills: every skilled worker knows how to avoid excess and deficiency, and is in a condition intermediate between two extremes. The courageous person, for example, judges that some dangers are worth facing and others not, and experiences fear to a degree that is appropriate to his circumstances. He lies between the coward, who flees every danger and experiences excessive fear, and the rash person, who judges every danger worth facing and experiences little or no fear.” | characterizes Virtue |

| IntelectualVirtue | “the various kinds of intellectual virtues: theoretical wisdom, science (epistêmê), intuitive understanding (nous), practical wisdom, and craft expertise.” | subkind of Virtue |

| TheoreticalVisdom | “exercising theoretical wisdom is a more important component of our ultimate goal than practical wisdom…” The happiest life is lived by someone who conducts virtuous activity based on theoretixal wisdom: “has a full understanding of the basic causal principles that govern the operation of the universe, and who has the resources needed for living a life devoted to the exercise of that understanding. Evidently Aristotle believes that his own life and that of his philosophical friends was the best available to a human being. He compares it to the life of a god: god thinks without interruption and endlessly, and a philosopher enjoys something similar for a limited period of time.” | subkind of IntelectualVirtue |

| PracticalVisdom | “practical wisdom (phronêsis), …. cannot be acquired solely by learning general rules. We must also acquire, through practice, those deliberative, emotional, and social skills that enable us to put our general understanding of well-being into practice in ways that are suitable to each occasion.” Mastery of politics is the highest level of practical wisdom. | subkind of IntelectualVirtue |

| EthicalVirtue | Ethical virtues are virtues of character, like courage, temperance, honor etc… “Ethical virtue is fully developed only when it is combined with practical wisdom… Aristotle describes ethical virtue as a ‘hexis‘ (‘state’ ‘condition’ ‘disposition’)—a tendency or disposition, induced by our habits, to have appropriate feeling. Defective states of character are hexeis (plural of hexis) as well, but they are tendencies to have inappropriate feelings. The significance of Aristotle’s characterization of these states as hexeis is his decisive rejection of the thesis, found throughout Plato’s early dialogues, that virtue is nothing but a kind of knowledge and vice nothing but a lack of knowledge. Although Aristotle frequently draws analogies between the crafts and the virtues (and similarly between physical health and eudaimonia), he insists that the virtues differ from the crafts and all branches of knowledge in that the former involve appropriate emotional responses and are not purely intellectual conditions.” | subkind of Virtue |

Sources

- All citations from: Kraut, Richard, “Aristotle’s Ethics”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 19/12/2019

Updated: 8/12/2021

Updated: 19/12/2021