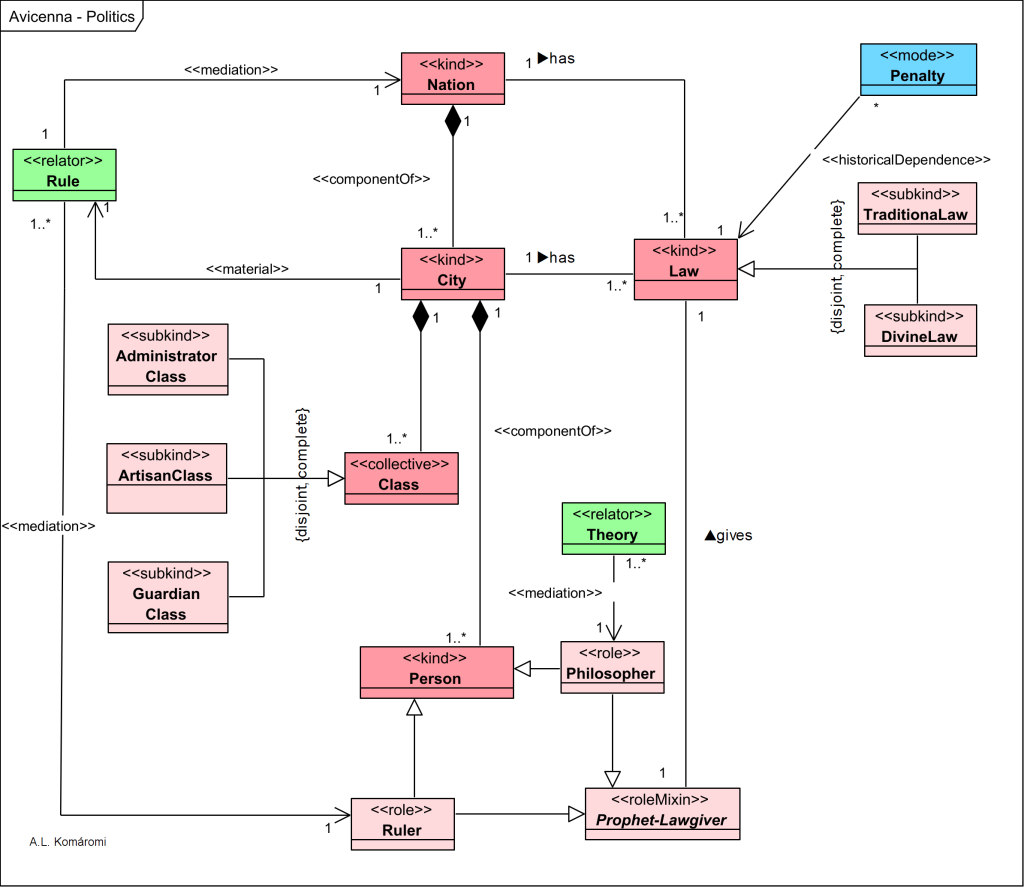

Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980-1037 AD) writes about political philosophy in the works Healing (Kita¯b al-Shifa¯ ’), Divisions (Fı¯ Aqsa¯m al-‘Ulu¯m al-‘Aqliyya) and Politics Kita¯b al-Siya¯sa). In these writings:

- He analyzes the subject with a strong emphasis on the role of the Prophet (not directly identified with Muhammad) in the creation of the political community.

- The Prophet, in his view, is a lawgiver, who delivers divine and traditional law as well to the nation and city.

- The persons living in a city are organized in three hierarchical classes, the Administrators, Artisans, and Guardians.

The following OntoUML diagram shows Ibn Sina’s on politics:

| Class | Description | Relation |

|---|---|---|

| Nation | The prophet, when creates divine law is “no longer concerned with mere cities and communities, his focus is now upon a nation (umma) – one of such a size that people may have to migrate or travel long distances in order to reach the spot designated as his abode. Even the time for which he wishes to preserve his laws and teaching has expanded. (Meta, 444:16–445:1). He now thinks it important for the people to remember these things for more than a century or two (Meta, 445:9–10).” For the prophet, the nation is necessary for providing security for the pilgrimage (hajj). | has Law |

| City | “Merely to feed and clothe ourselves, we must enter into exchange relationships with other individuals. To perpetuate such relationships and to give them structure, human beings form cities and communities.” | is exclusive part of the Nation; has Law |

| Law | “It is then necessary for these larger associations to be regulated and for there to exist a standard on which exchange is based, in other words, for there to be law and justice (Meta, 441:3–12). In all of this, says Avicenna, his goal should be to keep matters as simple as possible so that all citizens agree on the principles and do not enter into disputations about beliefs such as would lead them to neglect their civic duties – the fulfillment of those duties being, after all, the whole purpose of his lawgiving (Meta, 442:8–443:9).” | |

| TraditionalLaw | “The kind of law Avicenna mentions […] as needed to regulate relationships of exchange is traditional law (sunna). […] the prophet sets forth a traditional law (sunna) containing precepts about God and the after-life that are needed for a people to come together in communal association.” However, this kind of law, established by example, was known in pagan communities also. The Greek philosophers used the term nomos for it. | is subkind of Law |

| DivineLaw | Divine law (sharı¯‘a) is revealed by God and helps people to prepare their souls for happiness in the after-life. | is subkind of Law |

| Penalty | “Because fear of punishment in the life to come does not suffice to restrain all people from wrongful deeds, Avicenna notes that the prophetlawgiver must set down punishments, penalties, and prohibitions to prevent them from disobeying ‘the divine law’ (al-sharı¯‘a; see Meta, 454:2–4)” [and traditional law]. | characterizes Law |

| Class | “Avicenna begins his enumeration of the prophet lawgiver’s political ordering by noting that his first objective is to provide the city with three classes or orders administrators, artisans, and guardians (Meta, 447:4–5). Reminiscent as such an ordering is of Plato’s Republic, even though administrators here take the place of Socrates’ philosopher-kings, Avicenna does not elaborate on the idea.” | Class is exclusive part of the City; is a collection of Persons |

| AdministratorClass, ArtisanClass, GuardianClass | Administrators, Artisans and Guardians are three classes of the City. | subkind of Class |

| Person | A human person. | |

| Prophet-Lawgiver | “The best or most virtuous of human beings is the one who has so perfected his soul that he has become fully rational and acquired the practical moral habits permitting him to manage his own affairs in an excellent manner. And among those who reach this level of accomplishment, the prophet [lawgiver] is the best. Two additional qualities give him this edge of superiority, namely, his ability to hear the speech of God and to see God’s angels (Meta, 435:6–16). […] Differently stated, the prophet completes the partial lives of the philosopher and the virtuous ruler. The philosopher has a fully developed intellect, but apparently lacks the practical moral habits whose mastery would allow him to manage his own affairs or those of others that is, to rule others – and while the virtuous ruler surely has the latter, he seems to lack the former. Yet this by no means implies that the previously asserted affinity between philosophy and revealed religion is now rejected: on the grounds stated, philosophers can understand the superiority of prophets just as easily or readily as those who embrace the revelation prophets bring.” | is the roles of Philosopher and Ruler; gives Law |

| Ruler | The ruler has “practical moral habits whose mastery would allow him to manage his own affairs or those of others”. | Role of Person; Rules City and/or Nation |

| Rule | Rule: the act of ruling. | Relates ruler to City and Nation |

| Philosopher | “The philosopher has a fully developed intellect, but apparently lacks the practical moral habits whose mastery would allow him to manage his own affairs or those of others that is, to rule others” | Role of Person |

| Theory | A philosophical theory related to the philosopher. | Relates to Philosopher |

Sources

- All citations from: Charles E. Butterworth, The Political Teaching of Avicenna, Topoi-an International Review of Philosophy, 2000

- M. Cüneyt Kaya, In the shadow of “prophetic legistlation”; the venture of practical pilosophy after Avicenna, Arabic Sciences and Philosophy, vol. 24 (2014) pp. 269–296 doi:10.1017/S0957423914000034 © 2014 Cambridge University Press

First published: 27/2/2020

Update: 6/3/2021 added Rule, Theory