Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980-1037 AD) was the most crucial logician in the Arabic tradition. He synthesized, re-framed and extended the problems and solutions inherited from Aristotle and the Peripatetic tradition, e.g.:

- enriched Aristotelian term logic [3.3.9] with the systematical and detailed consideration of modality and reading (see Categorical Propositions),

- introduced propositional logic different from the Stoic one [3.5.4] (see Hypothetical Propositions).

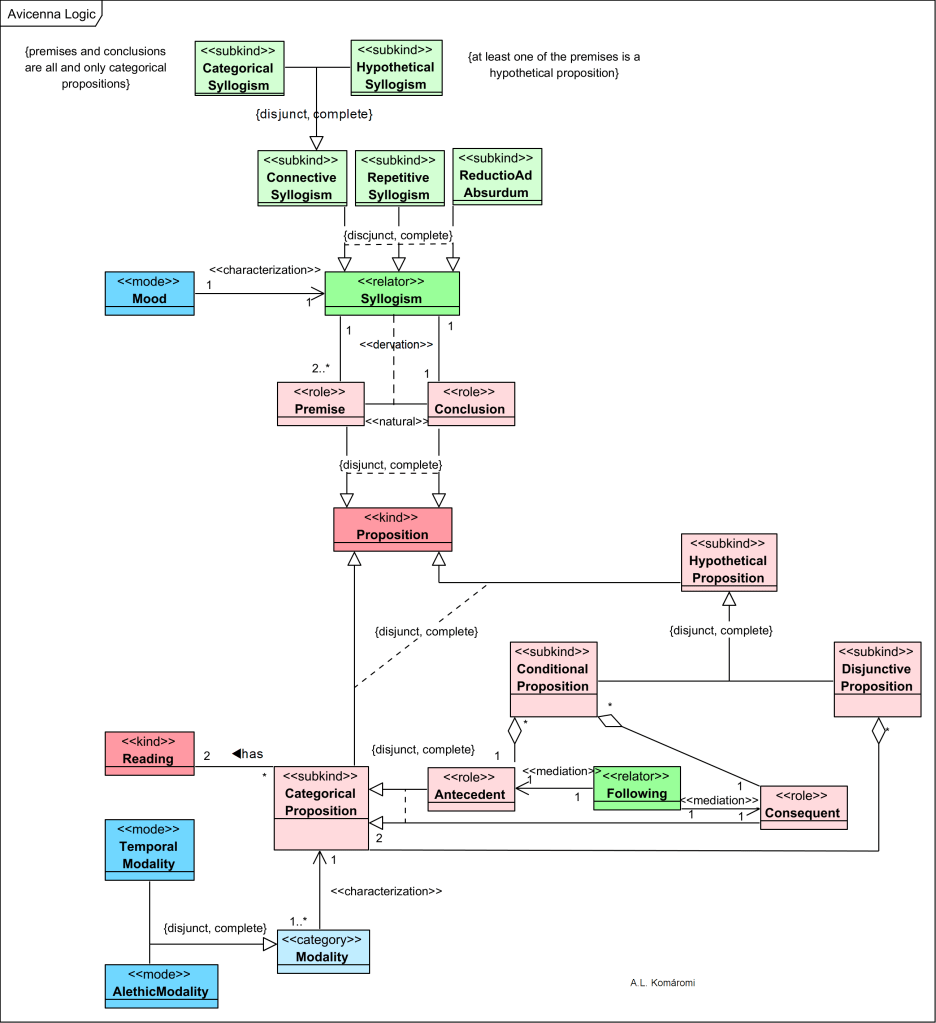

Here is a very high level OntoUML representation of Avicenna’s logic:

| Class | Description | Relations |

| Proposition | Proposition (qaḍiyya) according to Avicenna can be (1) categoricals, and (2) hypotheticals. | |

| Categorical Proposition | “Categorical (ḥamliyyāt) propositions are subject (mawḍūʿ)-predicate (maḥmūl) propositions expressing a relation (nisba) or judgment (ḥukm) between terms.” E.g.: “Avicenna is man.” “All man are mortal.” | is Proposition |

| Hypothetical Proposition | “Hypotheticals (šarṭiyyāt) comprise two main sub-types, depending on whether the component sentences are in connection (ittiṣāl) or in conflict (ʿinād)… The resulting propositional types are conditionals (muttaṣilāt) and disjunctions (munfaṣilāt)…” | is Proposition |

| Conditional Proposition | The Conditional proposition is formulating a relation of following (ittibāʿ) between and two propositions, an antecedent (muqaddam) and a consequent (tālin). E.g. “If [the sun rises], then [it is day].” | is Hypothetical Proposition |

| Disjunctive Proposition | The Disjunctive Proposition expresses a conflict in terms of a disjunction of propositions (or parts, ağzāʾ). E.g. “Either [this number is even] or [<this number> is odd].” | is Hypothetical Proposition |

| Antecedent | Antecedent is a possible role of a Categorical Proposition in a Conditional Proposition, where designates a condition. E.g. “[the sun rises]” | is shared part of Conditional proposition; is Categorical Proposition |

| Consequent | Consequent is a possible role of a Categorical Proposition in a Conditional Proposition, where designates a consequence of the Antecedent. E.g. “[it is day].” | is shared part of Conditional proposition; is Categorical Proposition |

| Following | The relation of following between antecedent and consequent in conditional propositions. | Relates Antecedent with Consequent |

| Modality | Modality: “every categorical proposition is modalized, either implicitly or explicitly. The modality may be either temporal […], alethic […], or a combination of both.” | Characterizes Categorical Proposition |

| Temporal Modality | Temporal Modality can be e.g.: sometime, always, never etc. | inherits from Modality |

| Alethic Modality | Alethic Modality can be e.g.: necessarily, possibly, impossibly etc. | inherits from Modality |

| Reading | “every categorical proposition is subject to an additional reading, depending on whether the proposition is taken to express a relation between the predicate and what is picked out by the subject:” (a) referential/substantial (ḏātī): “as long as what is picked out by the subject exists (mā dāma mawğūd aḏ-ḏāt) or (b) descriptional (waṣfī): “as long as it is qualified—or ‘described’ (mā dāma mawṣūf)—by the subject. This move amounts to adding a temporal parameter that identifies” | is related to Categorical Proposition |

| Syllogism | Sillogism is an inference with two ore more premises, and having as conclusion a proposition. the terms of which are just those two terms not shared by the premises. E.g. P1: “All man are mortal.” P2: “Avicenna is man,” C: “Avicenna is mortal.” | relates 2 or more premises and 1 conclusion; |

| Connective Syllogism | “Connective syllogisms are divided into two main types: (1) categorical (ḥamlī) and (2) hypothetical (šarṭī) syllogisms.” | is Syllogism |

| Repetitive Syllogism | “The repetitive (istiṯnāʾī) syllogistic covers inference patterns such as modus ponens and modus tollens (in their conditional and disjunctive variants)… Repetitive syllogisms consist of (i) a hypothetical premise (conditional or disjunctive) containing the conclusion or its negation as one of its parts, and (ii) another premise which asserts or denies (and thereby “repeats”) part of the hypothetical premise.” | is Syllogism |

| ReductioAd Absurdum | “A reductio [ad absurdum] is a compound syllogism (qiyās murakkab)—i.e., a concatenation of syllogisms—consisting of a connective hypothetical syllogism and of a repetitive syllogism. Both categorical and hypothetical propositions may be proved by reductio.” | is Syllogism |

| Categorical Syllogism | “Categorical syllogisms are those whose premises and conclusions are all and only categorical propositions.” | is Connective Syllogism |

| Hypothetical Syllogism | “The hypothetical syllogistic investigates arguments in which at least one of the premises is a hypothetical proposition (of type (i), namely one whose parts are themselves categoricals. Purely hypothetical syllogisms are those in which the combination of the premises involve only hypotheticals (conditional-conditional; conditional-disjunction; disjunction-disjunction). Mixed hypothetical syllogisms are those in which the combination of the premises involves a hypothetical (conditional or disjunction) and a categorical.” | is Connective Syllogism |

| Mood | Moods are formalized templates of valid (productive) syllogisms | Characterizes syllogism |

Sources

- All citations from: Strobino, Riccardo, “Ibn Sina’s Logic”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 29/08/2019

Updated: 6/3/2021 added Following