The area of topical logic, – like many others – was founded by Aristotle in his work “Topics”, and continued by Cicero and Boethius, whose work exercised an enormous influence on medieval logic.

The aim of topical logic is to provide a practical heuristic method for finding credible, plausible (not necessarily true) arguments which can be used in situations where persuasion is needed, e.g. in a legal process. Boethius, in his book “On Topical Differentiae” presents topical arguments in a quasi-syllogistic structure, thus finding a good argument is identifying the middle term which links the extremes (see [1.3.9]).

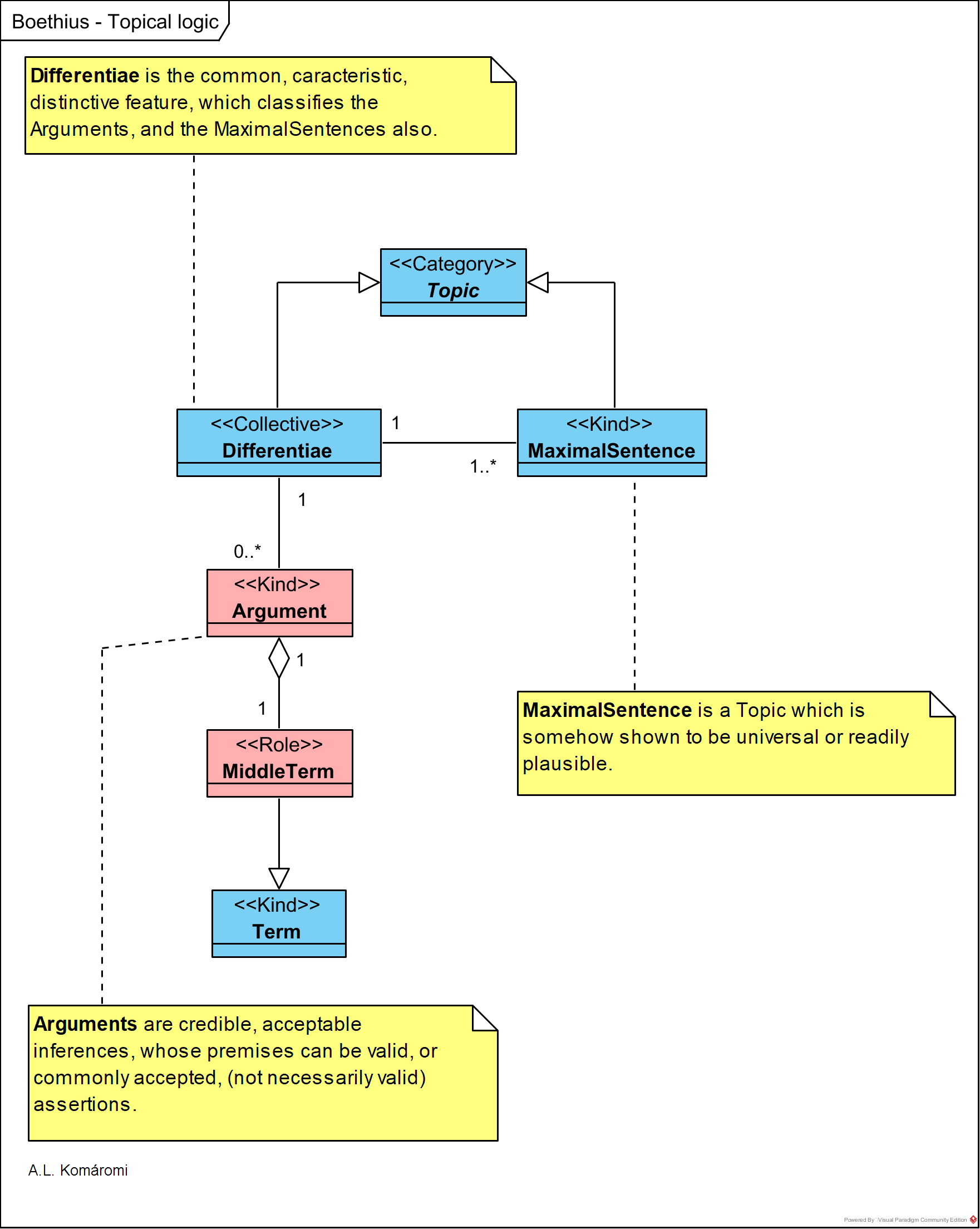

The following OntoUML diagram presents the main concepts in the Topical Logic of Boethius (477-525 AD):

| Class | Description | Relations |

| Topic | Topic (locus) can be Differentiae and Maximal Sentences. | |

| Differentiae | Topical Differentiae are the common, caracteristic, distinctive feature, which classifies the Arguments, and the MaximalSentences also. Boethius lists over 30 Differentiae, like: – “from the lesser” – “from an efficient cause” – “definition” | A Differentiae is assotiated with at least one MaximalSentence; and with 0, 1 or many Arguments |

| MaximalSentece | Maximal Sentence (maxima propositio) is a Topic which is somehow shown to be universal or readily plausible. This way “will help to suggest exactly what sort of argument can be made using the differentia in question”, gives power to the Argument. E.g. for the Differentiae “from an efficient cause” he lifts the following Maximal Sentences: – “Those tings who have a natural efficient cause are themselves also natural.” – “Where there is the cause, the effect cannot be ansent.” – “Everything should be considered according to its causes.” | |

| Argument | Arguments are credible, acceptable inferences, whose premises can be valid, or commonly accepted, (not necessarily valid) assertions (see [1.3.9]). | Each Argument contains a MiddleTerm |

| MiddleTerm | See in [1.3.9] also: The term shared by the premises is the Middle Term. | MiddleTerm is are a role of a Term |

| Term | See in [1.3.9] also: Subjects and predicates of Arguments are Terms which can be either individual, e.g. Socrates, or universal, e.g. human. Subjects may be individual or universal, but predicates can only be universals. |

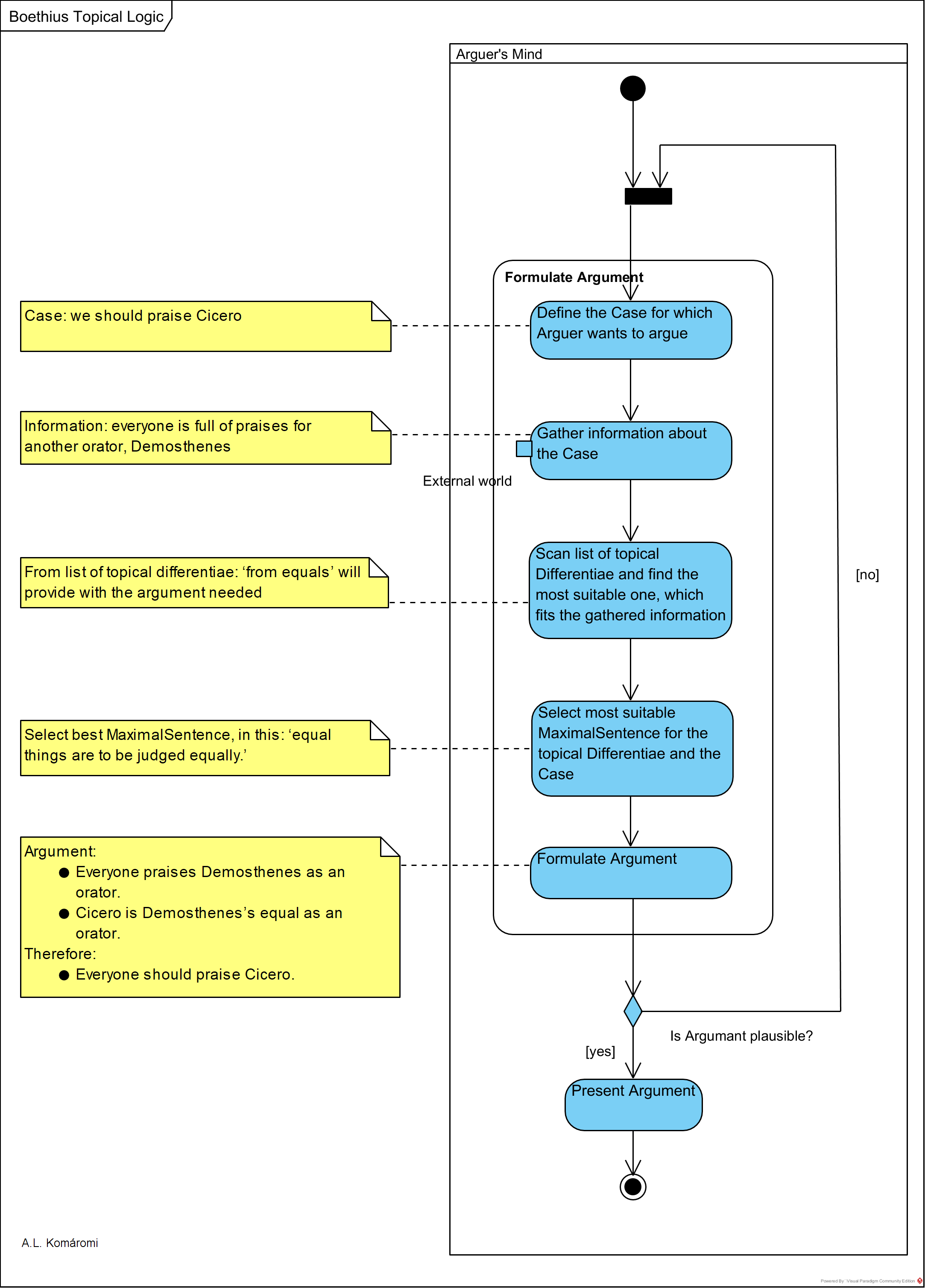

The UML activity diagram below shows the heuristic process of topical logic:

Sources

- All citations from: Marenbon, John, Boethius, Oxford University Press, 2003

- Case presented in Activity Diagram from: Marenbon, John, “Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta

First published: 27/06/2019