John Buridan (Jean Buridan 1301-1358) in Summulae de Dialectica writes about supposition occurring in conventional (spoken and written) languages and mental language:

- Propositions (sentences) are made up of terms.

- Terms in a proposition refer to other terms – the suppositum (or supposita); this relation is called supposition. The supposition of a term always occurs in a propositional context and can be entirely different from its signification (see [4.0.1]).

- Written and spoken terms signify Concepts conventionally; Concepts signify Objects naturally.

- Buridan (in contrast to Ockham, see [4.0.2]) differentiated the mechanism of supposition for the different layers of language: for conventional (spoken and written) language supposition has various subkinds, like improper, proper, material, simple, personal. On the other hand, for the mental language we have only personal supposition, because “concepts signify just what is conceived by them— that is, just what they are thoughts of—and since in general it is only in personal supposition that terms supposit for what they signify” (Spade)

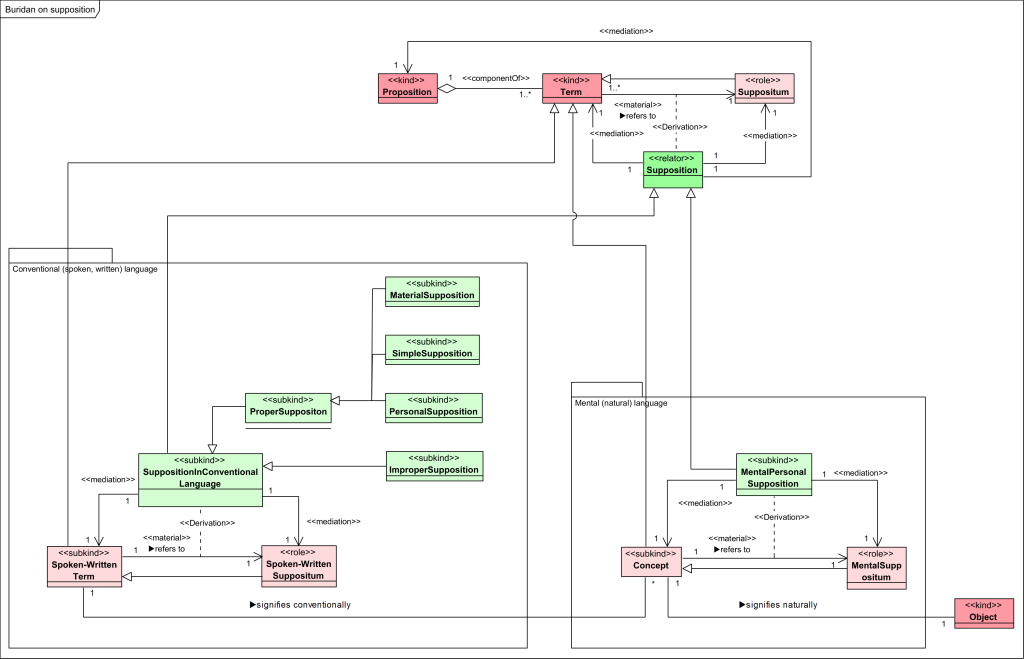

The following OntoUML diagram depicts Buridan’s theory of supposition (reference):

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Proposition | A proposition or sentence is made up of terms. | |

| Term | A mental, spoken, or written term. | shared part of proposition; refers to Suppositum |

| Suppositum | Suppositum is “whatever a term supposits for.” | role of Term |

| Supposition | “What sort of relation is supposition? Well, the first thing we can say about it is that supposition is a semantic relation. To a first (but pretty good) approximation, supposition in this first part of the theory is what nowadays we call ‘reference.’ It is the relation between the terms used in a proposition and the things those terms are used to talk about in that proposition. […] supposition occurs only in a propositional context. And this is the first main difference between supposition and signification, which can occur outside a propositional context according to almost any author. The second main difference is this: We do not always in practice use terms in propositions to talk about what those terms signify. We use them in a variety of other ways too. Hence supposition also differs from signification insofar as a term may signify one thing, but supposit on a given occasion for something entirely different.” (Spade) | relates Term, Proposition and Suppositum |

| Spoken-WrittenTerm | Spoken or written terms are utterances or inscriptions. | subkind of Term refers to Spoken_WrittenSuppositum; signifies conventionally Concept |

| Spoken-WrittenSuppositum | A spoken or written term in the context of a proposition refers to (supposits) a spoken or written suppositum. | role of Spoken_WrittenTerm |

| SuppositionInConventional Language | Supposition in conventional language is supposition occuring in spoken or written (conventional) languages. | subkind of Supposition; relates Spoken_WrittenTerm with Spoken_WrittenSuppositum |

| ImproperSupposition | “Improper supposition […] is the kind of supposition or reference a term has when it is used figuratively and not literally. Now a detailed semantics of metaphor was just as much beyond the reach of mediaeval authors as it is beyond our reach today. So we should not be surprised to find that the theory of improper supposition is not worked out very fully.” (Spade) | subkind of SuppositionIsnConventionalLanguage |

| ProperSuppositon | “proper supposition occurs when a term supposits for what it properly signifies” (Spade) | subkind of SuppositionInConventionalLanguage |

| MaterialSupposition; SimpleSupposition; PersonalSupposition | MaterialSupposition; SimpleSupposition; PersonalSupposition are subkinds of supposition. For conventional (written and spoken) languages Buridan accepts Ockham’s view on supposition. For more details please check [4.0.2]. | subkinds of ProperSuppositon |

| Concept | A concept is a term in mental language an act of understanding. “Buridan makes it quite clear that in his view a concept cannot vary its semantic features, which means that there is no ambiguity in mental language. The same concept always represents the same things in the same way, so there is not even a variation of supposition in mental language in the way there is in spoken or written languages” (Klima) | subkind of Term; refers to MentalSuppositum; signifies naturally Object |

| MentalSuppositum | A concept in the context of a (mental) proposition refers to (supposits) a mental suppositum. | role of Concept |

| MentalPersonalSupposition | Buridan makes it quite clear that in his view a concept cannot vary its semantic features, which means that there is no ambiguity in mental language. The same concept always represents the same things in the same way, so there is not even a variation of supposition in mental language in the way there is in spoken or written languages: We should know, therefore, that (as it seems to me), material material supposition occurs only where signifi cative utterances are concerned. For no mental term in a mental proposition supposits materially, but rather always personally, for we do not use mental terms by convention [ad placitum] as we do with utterances and written marks. This is because the same mental expression never has diverse signifi cations, or acceptations; for the affections of the soul [ passiones animae] are the same for all, just like the things of which they are the likenesses, as is said in bk. 1 of On Interpretation. […] A concept that represents some object does not signify it by virtue of anything else: to have such a concept active in one’s mind is just to conceive of the object in the way the concept represents it. This understanding of the representative function of a concept, however, immediately renders Ockham’s account problematic. For to have a concept active in one’s mind on this understanding is to conceive of the object represented by the concept, whereas the same concept may represent different objects. Sometimes it may represent its ordinary objects, as the concept of human beings does in the mental counterpart of ‘Man is an animal’. At other times, it may represent itself or a similar concept, as it does in the mental counterpart of ‘Man is a species’. Consequently, it would appear that one might not be sure just what one conceives of, for one may not be sure whether the same concept is to be taken to stand for itself or for its ordinary objects, just as one may not be sure about the supposition of the subject termof the corresponding spoken proposition. But this seems absurd, namely, that having a concept active in one’s mind, one is not sure what one conceives by that concept, given that having the concept active in one’s mind is nothing but conceiving of its object in the way the concept represents it. In his detailed analysis of the problem, Paul Spade put the point in the following way. “Since concepts signify just what is conceived by them— that is, just what they are thoughts of—and since in general it is only in personal supposition that terms supposit for what they signify, it follows that if mental terms may have simple or material supposition, we do not always know what we are asserting in a mental sentence.” (Klima) | subkind of Supposition; relates Concept with MentalSuppositum |

| Object | An object, a thing or state of affairs in the external (or internal) world. |

Sources:

- Klima, Gyula, “John Buridan”, Oxford University Press, 2009

- Spade, Vincent, “Thoughts, Words and Things: An Introduction to Late Mediaeval Logic and Semantic Theory”, Version 1.2: December 27, 2007

- Zupko, Jack, “John Buridan“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 20/9/2021 (szülinap edition)