Peter Abelard (“Doctor Scholasticus”, 1079?-1142 AD), in his work Logica Ingredientibus, introduced some novel ideas in the domain of logic:

- the distinction between force and content of a proposition

- the concept of entailment (inferentia), which is necessary for each argument.

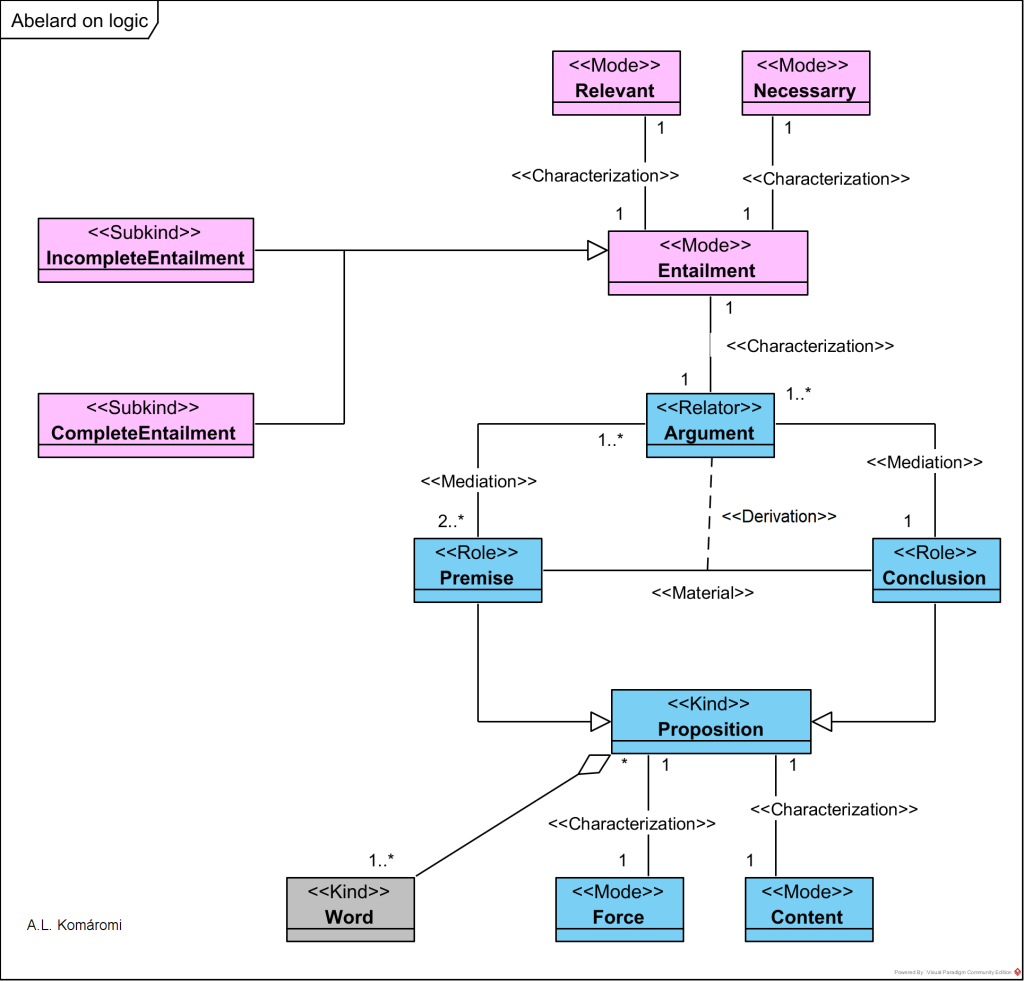

Abelard’s main concepts of logic is presented in the following OntoUML diagram:

| Class | Description | Relations |

| Argument | Arguments relates two (or more) Premises to a Conclusion. According to Abelard, it has to be characterized by entailment, meaning that the connection between the propositions involved to be both necessary and relevant. | mediates between Premise and Conclusion |

| Entailment | “The key to the theory of argument, for Abelard, is found in inferentia, best rendered as ‘entailment’ since Abelard requires the connection between the propositions involved to be both necessary and relevant. That is, the conclusion—more exactly, the sense of the final statement—is required by the sense of the preceding statement(s), so that it cannot be otherwise. Abelard often speaks of the sense of the final statement being ‘contained’ in the sense of the preceding statement(s), much as we speak of the conclusion being contained in the premisses.” | characterizes Argument |

| Relevant, Necessary | “Abelard requires the connection between the propositions involved to be both necessary and relevant.” | characterizes Entailment |

| IncompleteEntailment | “There is another way in which conclusions can be necessary and relevant to their premisses, yet not be formally valid (not be a complete entailment). The necessary connection among the propositions, and the link among their senses, might be a function of non-formal metaphysical truths holding in all possible worlds. For instance, human beings are a kind of animal, so the consequence ‘If Socrates is a human being, Socrates is an animal’ holds of necessity and the sense of the antecedent compels that of the consequent, but it is not formally valid under uniform substitution. Abelard takes such incomplete entailments to hold according to the theory of the topics (to be forms of so-called topical inference). The sample inference above is validated by the topic “from the species”, a set of metaphysical relations one of which is expressible in the rule “Whatever the species is predicated of, so too is the genus” which grounds the inferential force of the entailment. Against Boethius, Abelard maintained that topical rules were only needed for incomplete entailment, and in particular are not required to validate the classical moods of the categorical and hypothetical syllogism mentioned in the preceding paragraph.” (see also [2.7.2]) | is subkind of Entailment |

| CompleteEntailment | “An entailment is complete (perfecta) when it holds in virtue of the logical form (complexio) of the propositions involved. By this, Abelard tells us, he means that the entailment holds under any uniform substitution in its terms, the criterion now associated with Bolzano. The traditional four figures and moods of the categorical syllogism derived from Aristotle, and the doctrine of the hypothetical syllogism derived from Boethius, are all instances of complete entailments, or as we should say, valid inference.” | is subkind of Entailment |

| Proposition | A proposition is a sentence with a truth-value (true or false). | |

| Word | Proposition is made up of words. | is non-exlusive part of Proposition |

| Premise | Premise is a previous proposition from which another is entails or follows as a conclusion. | is subkind of Proposition; in material relation with Conclusion |

| Conclusion | Conclusion is a proposition which follows from a premise as result of an entailment. | is subkind of Proposition |

| Force | “Abelard observes that the same propositional content can be expressed with different force in different contexts: the content that Socrates is in the house is expressed in an assertion in ‘Socrates is in the house’; in a question in ‘“Is Socrates in the house?’; in a wish in ‘If only Socrates were in the house!’ and so on. Hence Abelard can distinguish in particular the assertive force of a sentence from its propositional content, a distinction that allows him to point out that the component sentences in a conditional statement are not asserted, though they have the same content they do when asserted— ‘If Socrates is in the kitchen, then Socrates is in the house’ does not assert that Socrates is in the kitchen or that he is in the house, nor do the antecedent or the consequent, although the same form of words could be used outside the scope of the conditional to make such assertions.” | characterizes Proposition |

| Content | “Abelard can distinguish in particular the assertive force of a sentence from its propositional content.” | characterizes Proposition |

Related posts: [1.3.9], [2.2.4], [2.7.2], [3.3.5]

Sources

- All citations from: King, Peter and Arlig, Andrew, “Peter Abelard”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 30/06/2020