Henry of Ghent (“Doctor Solemnis”, 1217?, d. 1293 AD) in Quodlibet II, q. 8 and V. q. 6 writes about ontology by analyzing the relation of thing, essence and being (existence):

- He agrees with Avicenna (see [3.3.1]) that every thing (res) possesses its essence (quidditas), which differs from its being (existence).

- An essence can be considered in itself, independently of its physical (or mental) existence. This means that being is not part of its content, so the essence – being distinction is not based on reason alone.

- On the other hand, being includes the concept of essence. “Being and essence are therefore different intentions, not different things.” So we have an intentional distinction between essence and being.

- Essences have a natural tendency towards non-being. Their existence depends on God’s creative and supportive act.

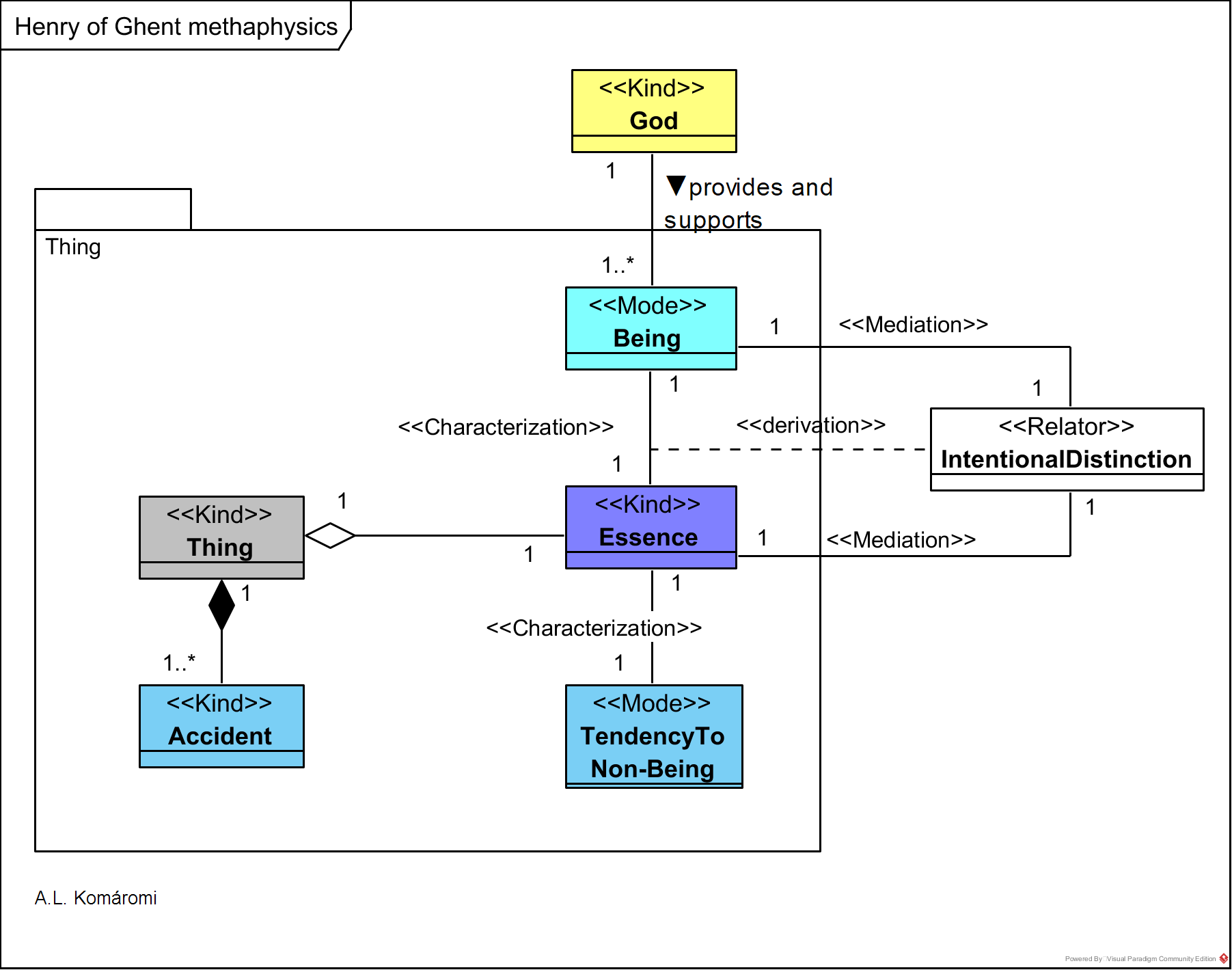

The following OntoUML diagram presents Henry of Ghent’s ontological model:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Thing | An enduring external material substance, a thing (res). | |

| Essence | “For Henry (as for Avicenna) every res possesses its own “certitude” (certitudo) that makes it what it is. Certitudo here means stability, consistency, and ontological self-identity: a triangle is a triangle and nothing else, white is white and nothing else. Certitudo thus expresses the objective content by which every thing is identical to itself and is distinguished from other things; in other words, certitudo expresses the essence or quidditas of a thing (“unaquaeque res habet certitudinem propriam quae est eius quidditas” — “every thing possesses its own certitude, which is its essence”). This content can be considered in itself, as independent from its physical or mental existence. In an absolute sense, every essence possesses a double indifference: with regard to actual existence or non-existence (essence in itself is simply possible), and with regard to universality and particularity. These last two aspects are really conjoined. Essence is particular in that it receives its subsistence in a given suppositum (concrete individual entity) from something-other-than-itself, while it is universal in that it is abstracted by the intellect from these singular supposita, in which it exists as one in many, in order to become predicable by many. Yet in itself essence is just essence: “essentia est essentia tantum”. Even though for both Avicenna and Henry thing (res) and being (ens) are primary notions (or rather intentions — intentiones — the sense of which we shall soon clarify), intentio de re seems to have a certain precedence over intentio de esse, at least logically, in virtue of its double indifference. | shared part of Thing |

| Accident | “anything that belongs to a thing, being external to the intention of its essence, can be called an accident.” | exclusive part of Thing |

| Being | “We still need to clarify in what sense existence can be said to be concomitant with essence. Being has access to essence from the outside, in the sense that it does not strictly belong to the essential nature of a res, except in the case of God. If this were not the case, a thing (every thing) would not simply be possible in itself, but necesse esse (necessary being) on a par with God. Instead, being seems to be an accident, or rather it has almost the mode of an accident (Quodl. I, q. 9). Nevertheless, it is not an accident in the real sense, since it is not added to something pre-existing, but is rather that by virtue of which a thing exists. In other words, we cannot refer here to the Aristotelian definition of accident (that which has its being in another thing or inheres in a subject), but once again to the broader definition given by Avicenna, according to which anything that belongs to a thing, being external to the intention of its essence, can be called an accident (“Sed intelligendum quod ‘accidens’ accipitur hic largissime, secundum quod iuxta modum loquendi Avicennae ‘accidens’ rei appellatur omne quod convenit ei et est extra intentionem suae essentiae”; Quodl. II, q. 8, ed. Wielockx, p. 48, ll. 21-23). In this sense an accident is anything that is external to the intentio of a res as absolute essence, without ever being really distinct from it. With regard to essence, actual being (that is, ratio suppositi) represents an accident of this type. Being is therefore an intentio that occurs to essence without adding anything real, and so it differs from essence only intentionally.” | charaterizes Essence |

| TendencyTo Non-Being | “every creatural essence tends naturally toward non-being [tendency to non-being] (in Avicennian terms, no possible essence, in the absence of a cause for its existence, could exist), though this inclination can be reversed by an external cause. No essence of a thing is so rigidly oriented toward nothing that it cannot receive being-in-act through a divine action. Similarly, even when placed, in act no thing ever possesses its being in an ultimate way: if God were to withdraw His support, it would fall into non-being.” | charaterizes Essence |

| IntentionalDistinction | Being and Essence according to Henry are the same thing, “While two distinct things differ in a real sense, all that gives rise to different concepts, albeit founded in the same simple thing, differs intentionally (“diversa intentione sunt quae fundata in simplicitate eisudem rei diversos de se formant conceptus.”; Quodl. V, q. 12, ed. 1518, f. 171rT). In an intentional distinction, in other words, the very same thing is expressed by different concepts in different ways. From this perspective, an intentional distinction seems akin to a purely logical (or reasoned) distinction, to the point that the two are often confused (“frequenter intentio ratio appellatur.”; Quodl. V, q. 12, ed. 1518, f. 171rV). Nevertheless, in the first case, one of the concepts excludes the other (one can be thought of separately, in the absence of the other), whereas in the case of a distinction based on reason the various concepts are perfectly compatible (“in diversis secundum intentionem unus conceptus secundum unum modum excludit alium secundum alium modum, non sic autem differentia sola ratione.”; Quodl. V, q. 12, ed. 1518, f. 171rV). As Henry explicitly states, this means that everything that differs in intention differs in reason too, but not vice versa. Unlike a purely logical distinction, an intentional distinction always implies a form of composition, even though this is minor with regard to that implied by a real difference. […] The distinction between being and essence belongs to the last mode [intentional distinction]. Since being is not a real accident inhering in a subject, it makes no sense to speak of a real distinction. Instead, the distinction depends on the fact that the intellect uses different concepts to indicate the being of a thing, on the one hand, and that which a thing is, on the other. Nevertheless, since essence can be thought of independently from its being, and being is not part of its content, we cannot refer here to a distinction based on reason alone. In other words, whereas the concept of actual existence always includes the concept of essence, the contrary is not true, since essence can be thought of without its being (as affirmed by Avicenna). Being and essence are therefore different intentions, not different things (as instead was maintained by Giles of Rome in his long dispute with Henry). This intentional distinction is in itself sufficient to refute the conclusion that every essence is its being.” | relates Being and Essence |

| God | Monotheistic God | provides and supports Being |

Sources

- All citations from: Porro, Pasquale, “Henry of Ghent”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Pickavé, Martin, “Henry of Ghent on Individuation, Essence and Being”, A Companion to Henry of Ghent, Brill, 2011, Gordon A.Wilson (ed)

First published: 25/3/2021