William Ockham (1285-1349 AD) in the works Summa of Logic and the Quodlibets uses his “razor” (see [4.18.4]) on Aristotle’s ten categories (substance; quantity; quality; relatives; somewhere; sometime; being in a position; having; acting; and being acted upon, see [1.3.2]), reducing them to a number of only three:

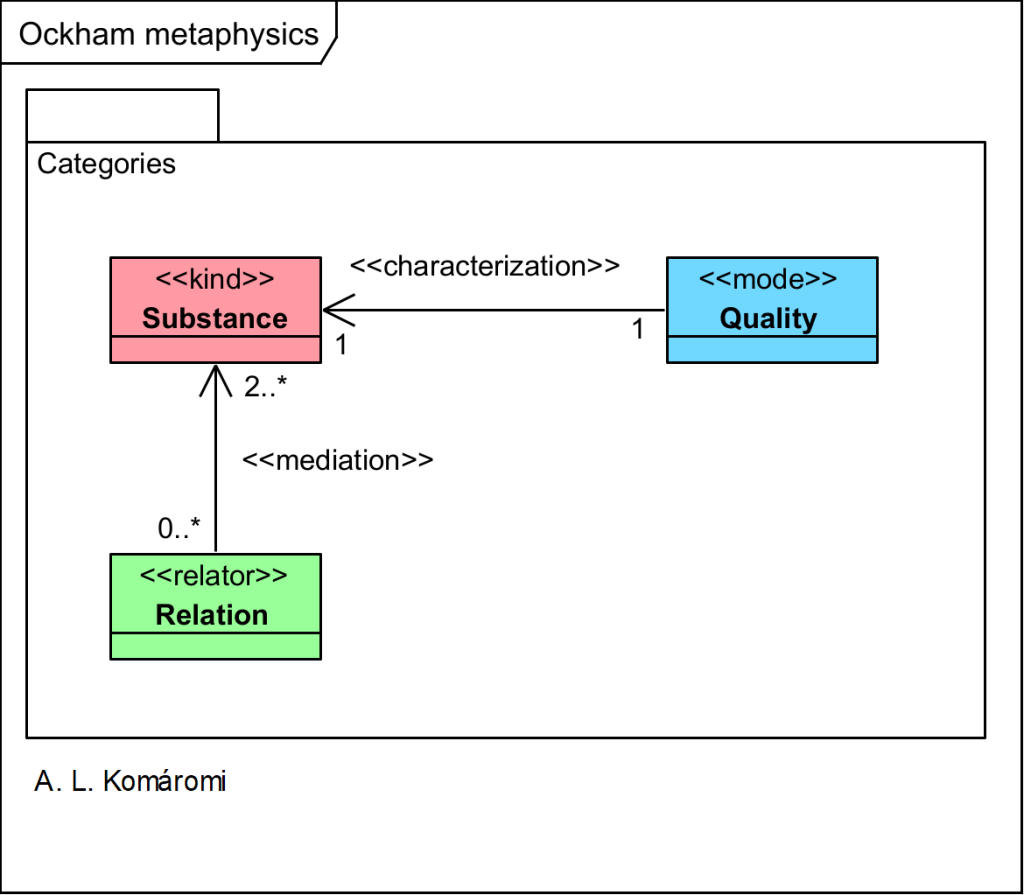

- His ontology consists of individual substances, individual accidents in the category of quality and a minimal number of relations necessary to explain some theological concepts.

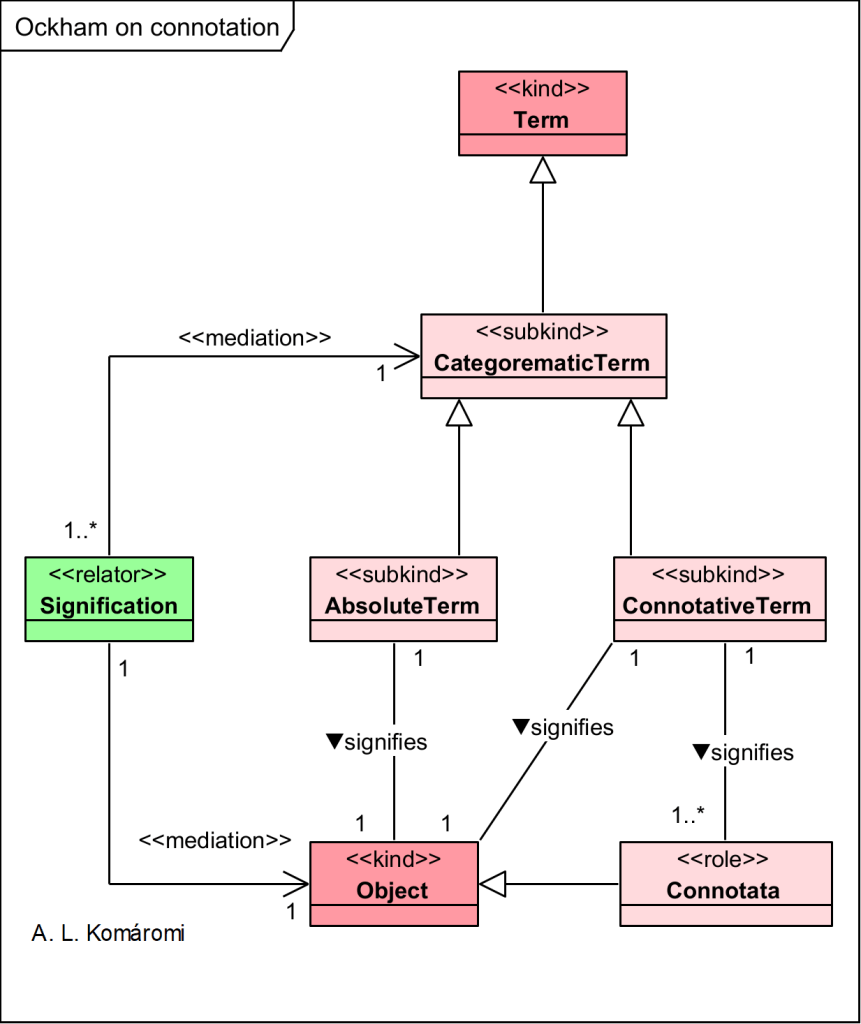

- His primary claim is that all our scientific absolute and connotative terms signify nothing but singular substances or qualities.

For example, in Summa of Logic, he presents his razor eliminating the relational entity “similarity” in the following way: “for the truth of ‘Socrates is similar to Plato’, it is required that Socrates have some quality and that Plato have a quality of the same species. Thus, from the very fact that Socrates is white and Plato is white, Socrates is similar to Plato and conversely. Likewise, if both are black, or hot, [then] they are similar without anything else added.“

The following OntoUML diagram presents the main classes of Ockham’s ontology:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Substance | “Ockham is prepared to say things really act or are acted on, are really related to one another, and so on, but he does not think the truth of these statements requires us to postulate real entities in the categories of action, passion, or relation. Things really act, but there are no actions; things are really related without relations (except for the few exceptional cases required by theology). Ockham ‘eliminates’ all the Aristotelian categories in this way – except for substance and quality.” | |

| Quality | “He [Ockham] allows individual qualities, for example; there are as many whitenesses as there are white things (although there is no universal whiteness). […] One wonders why he stopped there. Why is it not just as legitimate to say things are really ‘qualified’ but there are no qualities – things are really white or red, hot or cold, although there is no whiteness or redness, no heat or cold as a distinct accidental entity in the category of quality? If other categories can be eliminated without denying any of the ways things really are, why not quality too? In that case, we would end up with a single ontological category: substance. Substances would be qualified, quantified, related in different ways, would variously act and be acted upon, and so on, but there would be only substances. None of the richness of the world would be lost, only the illusion that we need distinct entities for all the different claims we want to make about things. […] Ockham does not explicitly address this question, but it is tempting to suppose the answer lies in the doctrine of the Eucharist interpreted according to the theory of transubstantiation. That theory holds that at the moment of consecration the bread and wine of the sacrament cease to exist and are replaced by the body and blood of Christ. But the accidents of the bread and wine remain (without inhering in the newly present body and blood of Christ, or in any other substance). This theory of course entails that the qualities of the bread and wine are real entities distinct from their substances.” | characterizes substance |

| Relation | Ockham allows that the supply of truths we want to maintain can come from several quarters: ‘For nothing ought to be posited without a reason given, unless it is self-evident or known by experience or proved by the authority of Sacred Scripture.” Theology, therefore, can provide evidence to answer ontological questions where unaided human reason would have inclined the other way.’ In discussing the category of relation, for instance, Ockham argues that there is no good pure reasoning, self-evident principle, or experience to indicate that there exist real relations distinct from their relata. But there do. The doctrine of the Trinity, as Ockham understood it, requires us to posit such relations in God. Likewise, the Incarnation requires a real relation of union between Jesus’s human nature and the Divine Word. And the Eucharist, understood according to the theory of transubstantiation, requires that the “inherence” of accidents in a substance be construed as a real relation distinct from its relata.” | relates substances (in very special cases postulated by the Scripture) |

Sources:

- All citations from: Spade, Paul Vincent, “Ockham’s Nominalist Metaphysics”, The Cambridge Companion to Ockham, ed. Paul Vincent Spade, Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Spade, Paul Vincent and Claude Panaccio, “William of Ockham”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 25/11/2021