Meister Eckhart (Eckhart von Hochheim 1260 – 1328 AD) in different works written in Latin and German language (Opus Tripartitum, Rechtsfertigungschrift/Defense Document, Essential Sermons, Commentary on Genesis and Commentary on St John) writes about two types of relations with an important role in the process of creation:

- The analogy relates the uncreated thing to the created (see also [4.16.1]), while the univocal causality has a role when a thing creates itself.

- Analogy describes the relation between God (uncreated) and all his creatures (created things).

- We have Univocal causality when the active principle of a thing causes its passive principiate; and this way the thing creates itself. We have this kind of relationship between the persons of Trinity, sight, and object of sight, intellect and object of intellect, just man and justice, free man and freedom etc.

The following OntoUML diagram shows Eckhart’s model of analogy:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Thing | An existent, a thing. | |

| Uncreated | An uncreated thing, i.e. God. | subkind of Thing; creates Created |

| Created | A created thing. | subkind of Thing |

| Analogy | “Between the uncreated and the created the predominant relationship is one of analogy, a relationship involving as well the disjunction of the two terms.” (Mojsisch, Summerell) | relates Uncreated with Created |

| Temporal | “The univocal relation is atemporal while the analogue relation is temporal.” (Hackett, Hart Weed) | characterizes Analogy |

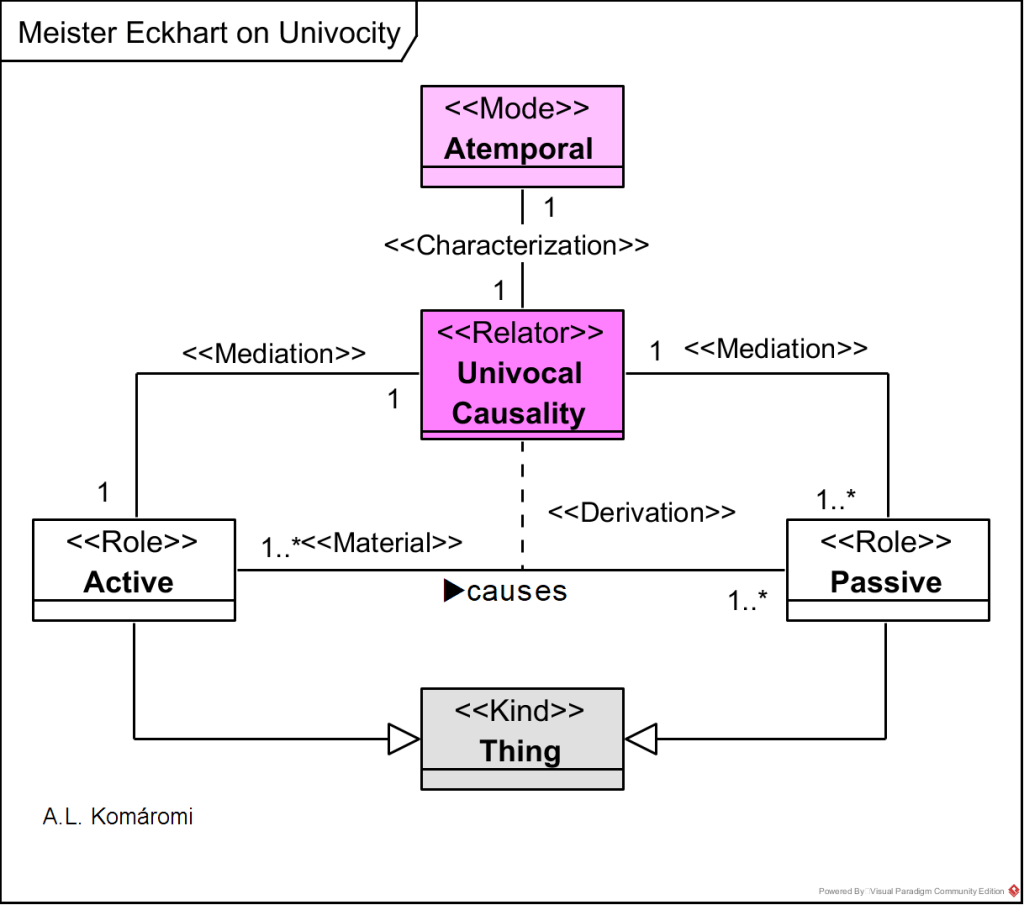

The following OntoUML diagram shows Eckhart’s model of univocal causality:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Thing | An existent, a thing. | |

| Active | “This means that the active (principle) is at the same time active and passive, being affected in the course of its activity (as principle). In turn, the passive (principiate) is at the same time passive and active, being active in the course of its passivity (as principiate). Accordingly, a central proposition of Eckhart reads as follows: ‘[Principium et principiatum]… opponuntur relative: in quantum opponuntur, distinguuntur, sed in quantum relative, mutuo se ponunt …‘ (Echardus, In Ioh. n. 197; LW III, 166, 10–12: ‘[The principle and the principiate] … are opposed to one another relatively: Insofar as they are opposed, they are distinguished, but insofar as they are relative, they reciprocally posit themselves …’). (Mojsisch, Summerell) | role of Thing; causes Passive |

| Passive | “This means that the active (principle) is at the same time active and passive, being affected in the course of its activity (as principle). In turn, the passive (principiate) is at the same time passive and active, being active in the course of its passivity (as principiate). Accordingly, a central proposition of Eckhart reads as follows: ‘[Principium et principiatum]… opponuntur relative: in quantum opponuntur, distinguuntur, sed in quantum relative, mutuo se ponunt …‘ (Echardus, In Ioh. n. 197; LW III, 166, 10–12: ‘[The principle and the principiate] … are opposed to one another relatively: Insofar as they are opposed, they are distinguished, but insofar as they are relative, they reciprocally posit themselves …’). (Mojsisch, Summerell) | role of Thing; |

| Univocal causality | “Eckhart, however, breaks through that metaphysics of being with its analogical base by thinking through the relation of causality informing absolute being. We can assume at least hypothetically that a cause causes not only something dependent on it, but also something equal to it, namely that the cause causes in such a manner that it causes itself. But if it causes itself, it causes something which is itself also cause and at the same time cause of its cause. Such a mode of causality is called ‘univocal causality’. Our hypothesis of what could be thought in these terms turns into a certainty when we explore the structures of intellectual causality, for example, the relation between the act of thinking and what is thought, or between an ethical principle and an ethical principiate. Their relation is precisely what Eckhart takes advantage of in developing his theory of univocal causality. In these cases, it holds that the principle causes its principiate, and the principiate causes its principle. Even more: The principiate is in its principle nothing other than its principle. […]” (Mojsisch, Summerell) “The breakthrough that Eckhart attains through his theory of univocal causality is exemplified by the relation between thinking and thought. For Eckhart, thinking presupposes no origin because a presupposed origin could only be thought by thinking and hence would be a thought of thinking, that is, itself thinking. Thinking is, then, for itself a presuppositionless origin, that is, it is its own principle: principium (Echardus, In Ioh. n. 38; LW III, 32, 11: “… ipsum principium semper est intellectus purus …”: “The principle itself is always pure intellect …”). Any thinking without act, however, is no thinking at all. Consequently, its own originative activity accrues to thinking, that is, insofar as it is a principle, the dynamics of its principiating: principiare. In this activity, however, thinking directs itself towards a thought that it has originated, that is, towards the product that is its principiate: “principiatum. But since this thought is a thought of thinking, it is itself nothing other than thinking. The act of this thinking that has been thought is, then, retrograde. This thought, as thinking, is in turn principle, principiating and principiate, whereby this last is the original thinking. In this way, thinking thinks itself as thought and is therewith active thinking, while thought, insofar as it thinks its thinking, is itself thinking, and its thinking now thought. Consequently, both thinking and thought are at the same time active and passive. […] The result of this analysis: Over against the external relationality of analogue relata, univocal correlationality involves an immanent relationality. Eckhart emphasizes the mutual relatedness of the moments univocal-casually interpenetrating one another . . . The agent imparts to the passive everything which it is able to impart, and the passive receives what has been imparted as its inheritance, not as something merely lent.” (Hackett, Hart Weed) | relates Active with Passive |

| Atemporal | “The univocal relation is atemporal while the analogue relation is temporal.” (Hackett, Hart Weed) | characterizes Univocal causality |

Sources:

- Mojsisch, Burkhard and Orrin F. Summerell, “Meister Eckhart“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Hackett, Jeremiah and Hart Weed, Jennifer: “From Aquinas to Eckhart on Creation, Creature, and Analogy”, A companion to Meister Eckhart, Brill 2013, edited by Jeremiah M. Hackett.

First published: 16/7/2021