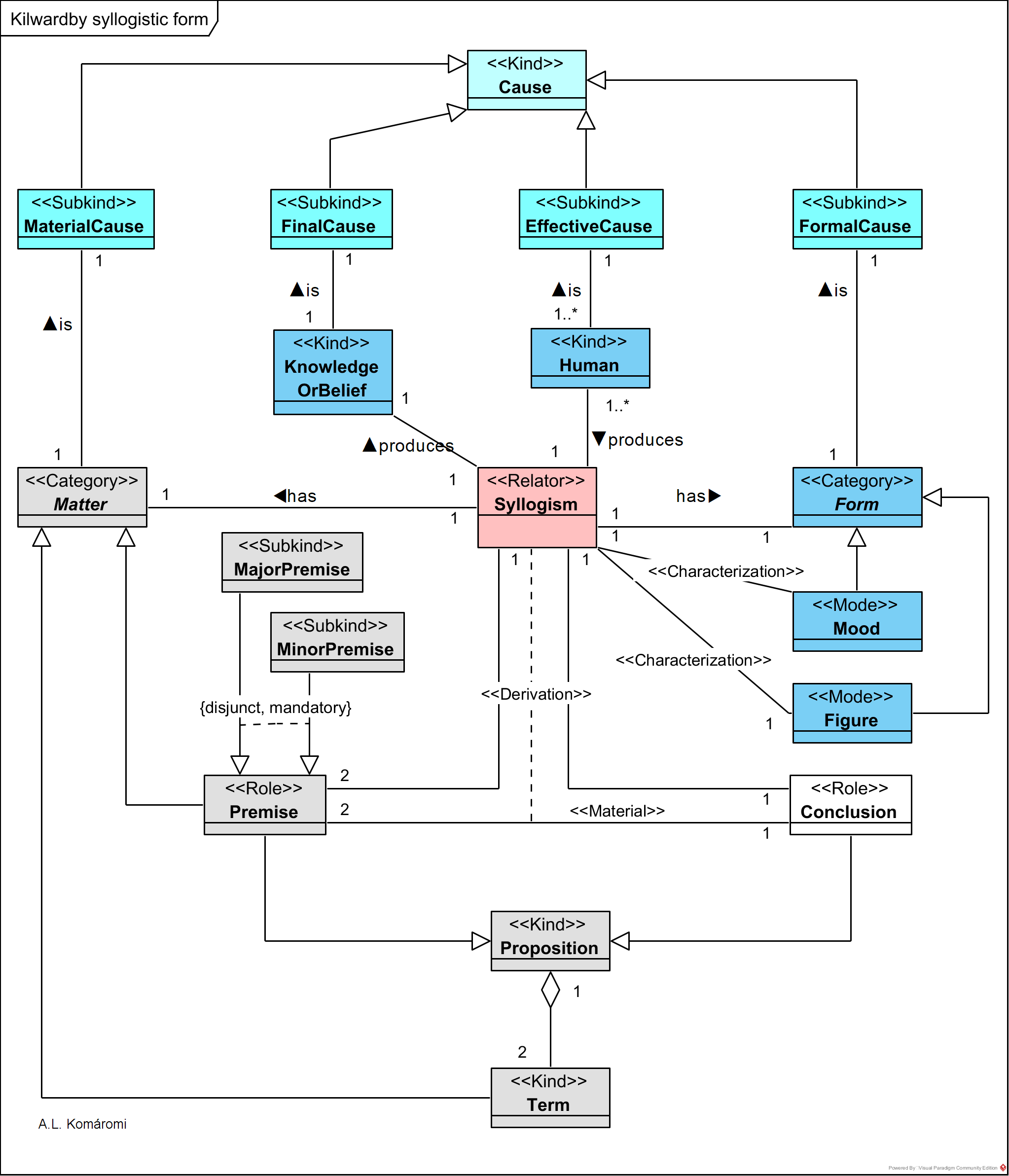

Robert Kilwardby (ca. 1215–1279 AD), in his commentary to Aristotle’s “Prior Analytics commentary,” enriches the Arostotelian logic (see [1.3.9]) with a few new perspectives:

- He applies the theory of four causes (see [1.3.4]) on syllogism and concludes that syllogisms, like any other objects, have material, formal, efficient, and final causes.

- Syllogisms have matter (the premises and terms) and form (the mood and figure), thus presenting a hylomorphic structure (see [1.3.5])

The following OntoUML diagram presents the main elements of Kilwarby’s hylomorphic syllogism:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Syllogism | “A syllogism is composed of form as well as matter.23 In elaborating on this idea, Kilwardby applies the Aristotelian doctrine of causes to the syllogism.” (Thom, 2013) A syllogism is an “inference with two premises, each of which is a categorical sentence, having exactly one term in common, and having as conclusion a categorical sentence the terms of which are just those two terms not shared by the premises”. (Smith, 2018) Not all the triplets of two premises and one conclusion of the required structure are syllogisms, only just those who lead to a valid inference, listed in the moods. E.g. P1: All man are mortal. P2: Socrates is man, C: Socrates is mortal. | has Form; has Matter; relates 2 Premises with 1 Conclusion; produces KnowledgeOrBelief |

| Proposition | Propositions (assertion, apophanseis) are sentences with a specific structure: “every such sentence must have the same structure: it must contain a subject and a predicate and must either affirm or deny the predicate of the subject.” (Smith, 2018) | |

| Term | “Subjects and predicates of assertions are terms (horos) which can be either individual, e.g. Socrates, or universal, e.g. human. Subjects may be individual or universal, but predicates can only be universals.”(Smith, 2018) | shared part of Proposition |

| Premise | A possible role of an Proposition, relative to a Syllogism is Premise (protasis). E.g. P1: All man are mortal. P2: Socrates is man. | in material relation with Conclusion; role of Proposition |

| MajorPremise | “The major premise occupies a determining role, since it is ‘contracted’ by the minor premise to produce the conclusion. Because of this relation between major and minor premise, Kilwardby reasons, the minor should not be counted along with the major; and so, he says, the Aristotelian definition of the syllogism rightly names oratio (in the singular) as its genus, not orationes.” (Thom, 2013) E.g. P1: All man are mortal. | subkind of Premise |

| MinorPremise | “The major premise occupies a determining role, since it is ‘contracted’ by the minor premise to produce the conclusion. (Thom, 2013) E.g. P2: Socrates is man. | subkind of Premise |

| Conclusion | A possible role of an Proposition, relative to an Syllogism is Conclusion (sumperasma). E.g. C: Socrates is mortal. | role of Proposition |

| Figure | “The middle term must be either subject or predicate of each premise, and this can occur in three ways: the middle term can be the subject of one premise and the predicate of the other, the predicate of both premises, or the subject of both premises. Aristotle refers to these term arrangements as figures (schêmata)”. (Smith, 2018) There are 3 Figures. | characterizes Syllogism |

| Mood | A Mood characterizes a syllogism, and is prooved with a Proof. There are 14 Moods, 4 for the First figure, 4 for the Second figure, and 6 fot the Third figure. | characterizes Syllogism |

| Matter | The matter of the syllogism “consists of two propositions (the major and minor premises) and three terms. It is worth noting that on Kilwardby’s account, the syllogism is materially constituted by two propositions, not three. The conclusion is not part of the syllogism; therefore, the syllogism is not a type of consequence. The syllogism’s two premises, however, possessa unity thanks to the fact that they aim at a single conclusion.” (Thom, 2013) E.g. matter in this example: Major premise: All man are mortal. Minor Premise: Socrates is man Terms: man, mortal, Socrates | is MaterialCause; generalizes Premise and Term |

| Form | “A syllogism’s form is the figure and mood as shown respectively by the relative position of the terms in the premises and by the premises’ quality and quantity; this is indicated by Aristotle when he says that in the syllogism certain things are posited (positis).” | is FormalCause; generalizes Mood and Figure |

| Knowledge OrBelief | “The demonstrative and dialectical syllogism also have a final cause, namely, the production respectively of knowledge or belief.” (Thom, 2013) | is FinalCause |

| Human | Human | produces Syllogism; is EfficientCause |

| Cause | “Aristotle places the following crucial condition on proper knowledge: we think we have knowledge of a thing only when we have grasped its cause (aitia).” (Falcon, 2019) | |

| MaterialCause | “The material cause: ‘that out of which’, e.g., the bronze of a statue. […] The bronze enters in the explanation of the production of the statue as the material cause. Note that the bronze is not only the material out of which the statue is made; it is also the subject of change, that is, the thing that undergoes the change and results in a statue. The bronze is melted and poured in order to acquire a new shape, the shape of the statue.” (Falcon, 2019) | subkind of Cause |

| FinalCause | “The final cause: ‘the end, that for the sake of which a thing is done’, e.g., health is the end of walking, losing weight, purging, drugs, and surgical tools.” (Falcon, 2019) | subkind of Cause |

| EfficientCause | “the actual syllogisms that people produce have efficient causes.” (Thom, 2013)) “The efficient cause: ‘the primary source of the change or rest’, e.g., the artisan, the art of bronze-casting the statue, the man who gives advice, the father of the child.” (Falcon, 2019) | subkind of Cause |

| FormalCause | “Formal cause, or the expression of what it is”, e.g., the shape of a statue. […] The bronze is melted and poured in order to acquire a new shape, the shape of the statue. This shape enters in the explanation of the production of the statue as the formal cause.” (Falcon, 2019) | subkind of Cause |

Sources

- Thom, Paul, “Robert Kilwardby on the Syllogistic Form”, A Companion to the Philosophy of Robert Kilwardby, Christopher Henrik Lagerlund and Paul Thom (ed), Brill, 2013

- Falcon, Andrea, “Aristotle on Causality“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Smith, Robin, “Aristotle’s Logic“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Silva, José Filipe, “Robert Kilwardby“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 11/2/2021