Albert the Great (Albertus Magnus, 1200?-1280 AD), in his paraphrase of Aristotle’s Organon, took the position that the universal’s mode of being should be analyzed based on its function. It may be considered in itself, or relative to understanding, or as existing in one individual. This way, he concluded, that both the nominalist and realist solutions to Porphyry’s questions are too simplistic.

He harmonized “Plato’s realism in which universals existed as separate forms with Aristotle’s more nominalistic theory of immanent forms”.

| Porphyry’s questions | Universals according to Albert |

| (a) whether genera and species [universals] are real or are situated in bare thoughts alone | they are real |

| (b) whether as real they are bodies or incorporeals | they are incorporeals |

| (c) whether they are separated or in sensibles and have their reality in connection with them | they are separated, but also in sensibles and have their reality in connection with them, based on the point of view of the analysis. |

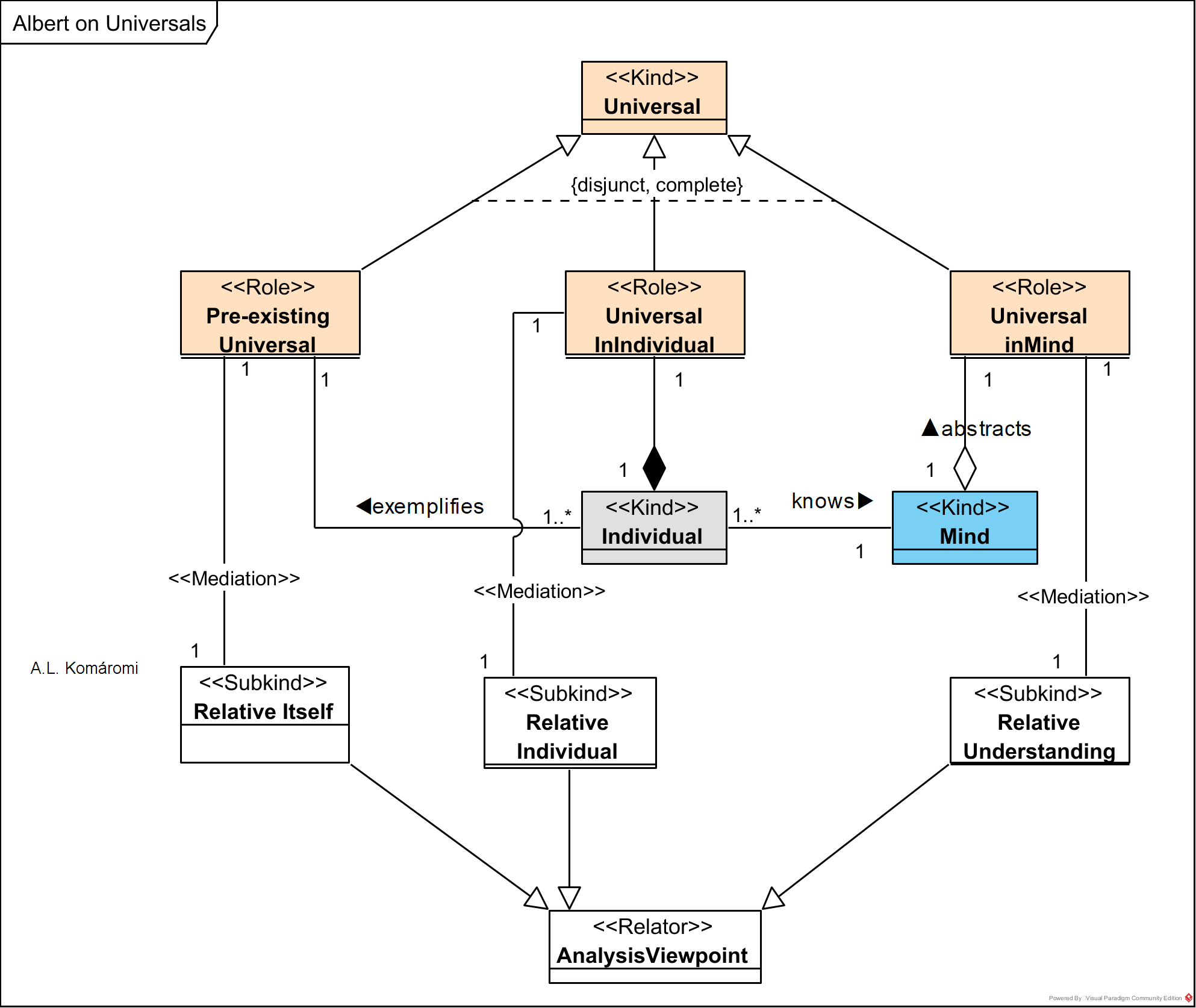

Albert’s model of universals is presented in the following OntoUML diagram:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Universal | Albert “defined the term universal as referring to ‘ … that which, although it exists in one, is apt by nature to exist in many.’ Because it is apt to be in many, it is predicable of them. (De praed., tract II, c. 1) He then distinguished three kinds of universals, those that pre-exist the things that exemplify them (universale ante rem), those that exist in individual things (universale in re), and those that exist in the mind when abstracted from individual things (universale post rem). […] Albert appealed to his three-fold distinction, noting that a universal’s mode of being is differentiated according to which function is being considered. It may be considered in itself, or in respect to understanding, or as existing in one particular or another. Both the nominalist and realist solutions to Porphyry’s problem are thus too simplistic and lack proper distinction. Albert’s distinction thus allowed him to harmonize Plato’s realism in which universals existed as separate forms with Aristotle’s more nominalistic theory of immanent forms.” | |

| Pre-existingUniversal | Pre-existing universals (universale ante rem): “For universals when considered in themselves (secudum quod in seipso) truly exist and are free from generation, corruption, and change” | is role of Universal |

| UniversalInIndividual | Universals in individal (universale in re): “But when they are considered in particulars (secundum quod est in isto vel in illo) their existence is exterior to as well as beyond the mind, yet existing in things as individuated.” | is role of Universal; exclusive part of Individual |

| UniversalInMind | Universal in mind (universale post rem) ar abstracted from individuals: “If, however, they are taken in reference to the mind (refertur ad intelligentiam) they exist in two modes, depending on whether they are considered with respect to the intellect that is their cause or the intellect that knows them by abstraction.” | is role of Universal; shared part of Mind |

| Mind | a human mind | knows Individual |

| Individual | an individual (or particular) | exemplifies Pre-existingUniversal |

| AnalysisViewpoint | The viewpoint form which we consider analize the Universal. | |

| RelativeItself; RelativeIndividual; RelativeUnderstanding | “Albert appealed to his three-fold distinction, noting that a universal’s mode of being is differentiated according to which function is being considered. It may be considered in itself, or in respect to understanding, or as existing in one particular or another.” | subkinds of AnalysisViewpoint; relates to (in order) Pre-existingUniversal; UniversalInIndividual; UniversalInMind |

Related posts in theory of Universals: [1.2.2], [1.3.1], [1.3.2], [2.5], [2.7.3], [4.3.1], [4.3.2], [4.4.1], [4.5.2], [4.9.8]

Sources

- All citations from: Führer, Markus, “Albert the Great”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 21/1/2021

Updated: 7/3/2021 added AnalysisViewpoint and its subkinds