In his work Ethics, Peter Abelard (“Doctor Scholasticus”, 1079?-1142 AD) elaborated his intentionalist theory according to which:

- Four factors involved in the performance of a deed are analyzed as potential bearers of moral worth: the desires of the agent, the agent’s character, the deed performed, and the agent’s intentions.

- Abelard, with the help of (sometimes extreme counterexamples), rules out the first three candidates, and concludes that only the intention has moral worth.

Abelard summarizes the moral worth of intentions on the following schema (after Peter King, 1992):

| Conforms God’s will | Doesn’t conform God’s will | |

|---|---|---|

| Agent believes to conform God’s will | good | depends on case |

| Agent believes not o conform God’s will | evil | evil |

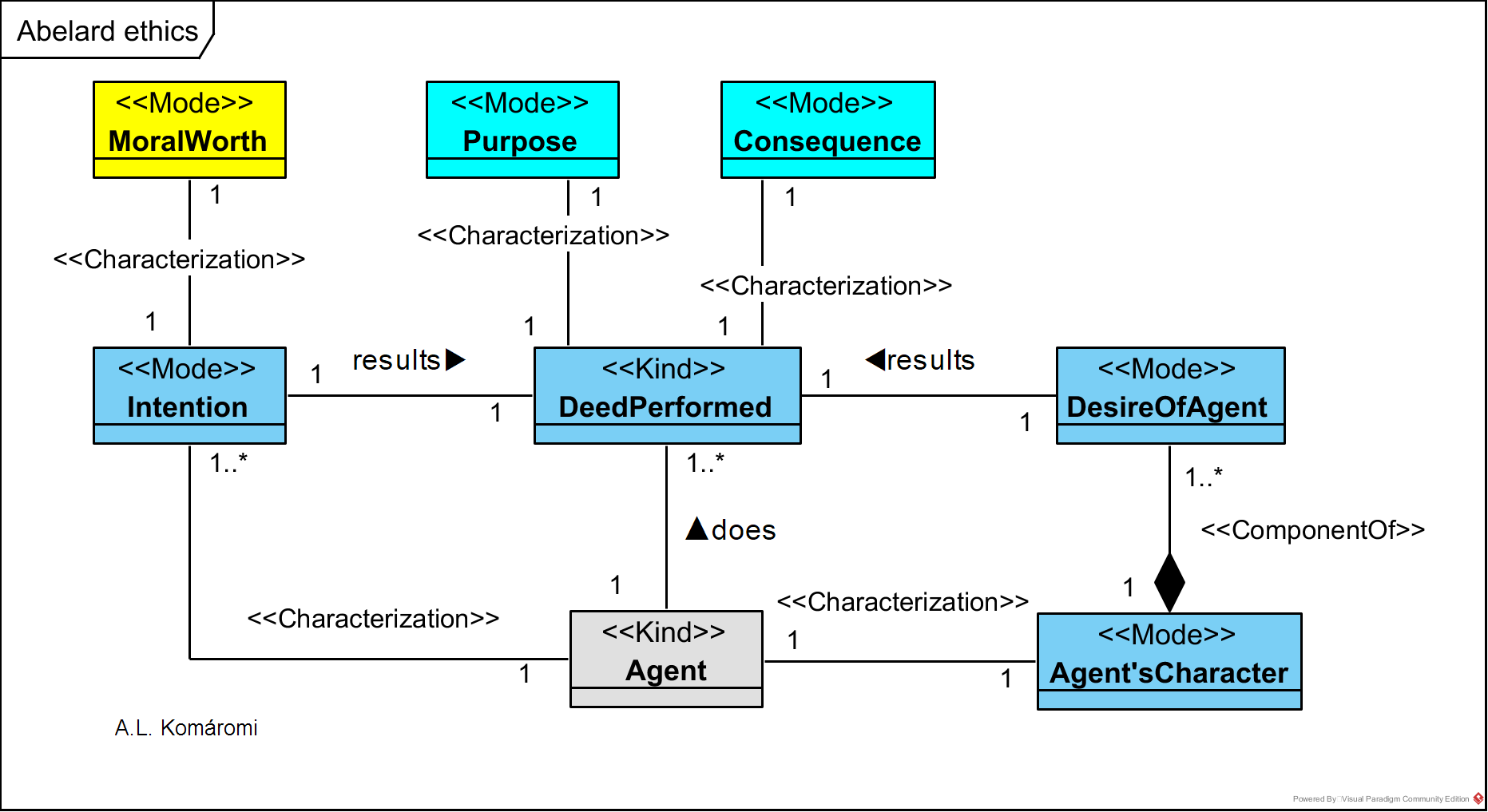

Abelard’s model of ethics is presented in the following OntoUML diagram:

| Class | Description (and why the class moral worth) | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| MoralWorth | Moral worth is “that which determines the moral quality of the deed.” | characterizes exclusively Intention |

| Agent | The agent is the human who performs a deed. | does DeedPerformed |

| Intention | “Abelard’s first positive argument on behalf of the agent’s intention as the key ingredient in moral worth is that there is no other way to make coercion and ignorance morally relevant. Ignorance, as a cognitive feature of the agent, seems utterly removed from any deed-based morality, and coercion seems equally removed as well. […] Abelard, typically, takes an extreme case to make his point. He argues that the crucifiers of Christ were not evil in crucifying Jesus. (This example, and others like it, got Abelard into trouble with the authorities, and it isn’t hard to see why.) The unbelief of Christ’s crucifiers does not suffice to make their intentions evil. Indeed, Abelard claims that they would have sinned if they had thought that crucifying Christ was required and did not crucify him (66.30–34): Those who persecuted Christ or his disciples, believing that they should be persecuted, ‘sinned in deed,’ but they would have committed a heavier sin in fact if they had spared Him against their own consciences. From this example Abelard draws two consequences. First, the only evil is to act against conscience. Now ‘conscience,’ for Abelard, is the faculty by which what is done is estimated to be pleasing or displeasing to God. Second, he offers a criterion for the goodness of intentions (55.20–23): An intention should not be called ‘good’ because it seems good, but because in addition it is just as it is assessed to be—that is, when, believing that what one intends is pleasing to God, one is not deceived in one’s own assessment. To formulate Abelard’s criterion briefly: An intention is good if and only if the intention is believed to and in fact does conform to God’s will. Any intention which is believed not to conform to God’s will is automatically evil, even if in fact it does conform to God’s will. If I intend something God” | results DeedPerformed |

| DeedPerformed | “Abelard attacks two ways in which the deed [performed] might be taken to ground moral worth. On the one hand, deeds are sometimes evaluated and justified on the basis of their purpose or their point; on the other hand, they are evaluated and justified in terms of their intrinsic nature or the consequences that flow from them. […] Nor will it help if we try to relativize evaluative terms to the ‘point’ of the deed, as some have taken Aristotle to do, so that the assessment of a deed depends on whether it is a good or bad instance of that type of deed. Just as a knife is good or bad qua knife if it does well or poorly at the things for which knives are designed, so too we might think that deeds embody evaluative criteria relative to the kind of deed they are. In Dialogus ll. 3254–3260 Abelard argues that this relativization of evaluative terms results in terms that are fundamentally non-moral: the deed specified by the description ‘baking a cake’ can be performed well or badly, it is true, but this is the case for any deed under any description. Robbing a bank can be done well or poorly, as can murder.” | |

| Purpose | “Abelard’s argument against the purpose of a deed is simple: take any deed for any given purpose, and you’ll be able to imagine a case in which the deed is performed for that purpose but the agent’s intention is evil. He offers two examples. First, Judas and Jesus each performed deeds with the same purpose: to bring it about that Christ be crucified. But Judas’s deed was evil, whereas Jesus’s was not (28.2–9);13 more generally, Satan does nothing but what God permits, and so the same deed with the same purpose (e. g. causing Job misery) is evil with respect to Satan but good with respect to God (28.18–24), Second, Abelard considers a situation in which the deed and the purpose of the deed is identical for each of two agents, but distinct intentions require us to render distinct moral verdicts (28.11–17; see also Dialogus ll. 3267–3272): Often the same thing is done by different people, [but] done through the justice of one and the iniquity of the other. For example, if two men hang a convict, one out of his zeal for justice and the other from the hatred stemming from an old enmity, although the act of hanging is the same and each does what it is good to do and what justice requires, nevertheless the same thing comes about through the difference in [their] intentions [so that] by one it is done well and by the other badly. The deed is identical and the purpose identical, but moral worth depends on the intention of the agent(s) involved.” | characterizes DeedPerformed |

| Consequence | “To show that the deed and its consequences or effects do not determine moral worth, Abelard begins by criticizing the alternative: the position that the performance or non performance of deeds is all that matters, a ‘strict liability’ ethical theory. This alternative might be thought especially attractive to traditional Christian teaching, since it proceeds by way of commandments: absolute prohibitions regarding performance and non-performance, such as ‘Thou shalt not kill.’ Abelard’s first objection to a strict liability theory is that such commandments, construed only with regard to the deed, fail to condemn those who are obviously evil, namely those who have nothing but the worst of intentions yet are never in a position to act on them. […] His second objection is that nobody can keep from violating such prohibitions. Abelard offers a version of the story of Oedipus: fraternal twins, male and female, are separated at birth and neither learns of the existence of the other; as adults they meet, fall in love, are legally married, and have sexual intercourse. Technically this is incest, but Abelard finds no fault in either to blame (26.14–23). If the deed alone determines moral worth, then on a strict liability theory their (justifiable) ignorance is morally irrelevant—which it manifestly is not. Absolute commandments, Abelard concludes, deprive the actor of any status as a moral agent. Abelard expands his attack on the deed and its consequences with a pair of cases centering around what recently has been called ‘moral luck’: cases in which nonmoral factors enter into or affect the possibility of moral actions. His first case is that of hypocrites and the wealthy. Such individuals are far better motivated (by the love of praise) and situated (by their riches) to perform acts that have wide effects and far-reaching consequences than the ordinary individual. But surely these aren’t morally relevant factors, even if views taking the deed to be the sole determinant of moral worth must count them as such (28.24–26). Abelard’s second case has to do with two men, each with the money and intention to build poorhouses; the first is robbed before he can act, while the second is able to build the poorhouses. To maintain that there is a moral difference between the two men is, Abelard says, to hold that (48.21 28): . . . the richer men were, the better they could become. To think this, namely that wealth can contribute anything to true happiness or to the worthiness of the soul, is the height of insanity!” | characterizes DeedPerformed |

| DesireOfAgent | “Abelard argues that some deeds pre-theoretically taken to be evil can be performed without any evil desire [of agent]. He establishes this by an example of self-defense (6.24–29): Consider some innocent man whose cruel lord is so furious at him that he chases him, brandishing a sword, to kill him; that man flees as far as he is able to avoid his own murder, yet finally he unwillingly kills (his lord) lest he be killed by him. Tell me, whoever you are, hat he had an evil desire in this deed!” | results DeedPerformed; componentOf Agent’sCharacter |

| Agent’sCharacter | “Abelard holds that [agent’s] character traits are simply complex patterns of mental dispositions of desire and feeling (2.21–22). To be irascible, for example, is to be prone to or ready for the emotion of anger. The previous rejection of desires as determining moral worth immediately leads to rejecting character as determining moral worth—since desires themselves lack moral value, so a fortiori dispositions-to-desire lack moral worth. There are no facts about the dispositions that could make them different, in the morally relevant way, from desires. Abelard offers an additional argument against character traits as determining moral worth. It is a fact that good and bad men can have much the same set of character traits; thieves can be courageous, honest men intemperate. But whatever can “occur in both good and evil men is not relevant to morality” (2.13–14). Any characteristic present in good men which is present in evil men cannot be that which makes the good men good since its presence in the evil men would make them good.” | characterizes Agent |

Sources

- All citations from: Peter King, The Modern Schoolman 72 (1995), 213–231

- King, Peter and Arlig, Andrew, “Peter Abelard”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 13/08/2020