St Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109 AD) in the works “On Truth” (De veritate), “On Freedom of Choice” (De libertate arbitrii), and “On the Fall of the Devil” (De casu diaboli) worked out a metamodel of rectitude (truth) according to which not only statements, but wills, actions, the senses, essences can be right or wrong.

Based on this metamodel he elaborated a theory of freedom of will, where

- He defines freedom as “the power to preserve rectitude of will for its own sake”.

- God and the angels are free, and they always preserve the rectitude of their will. So their freedom is stronger than that of humans and fallen angels.

- Humans are free, but they can not preserve their rectitude of will without the help of divine grace.

- Fallen angels are free, but they lost their rectitude of will by not using it according to its purpose.

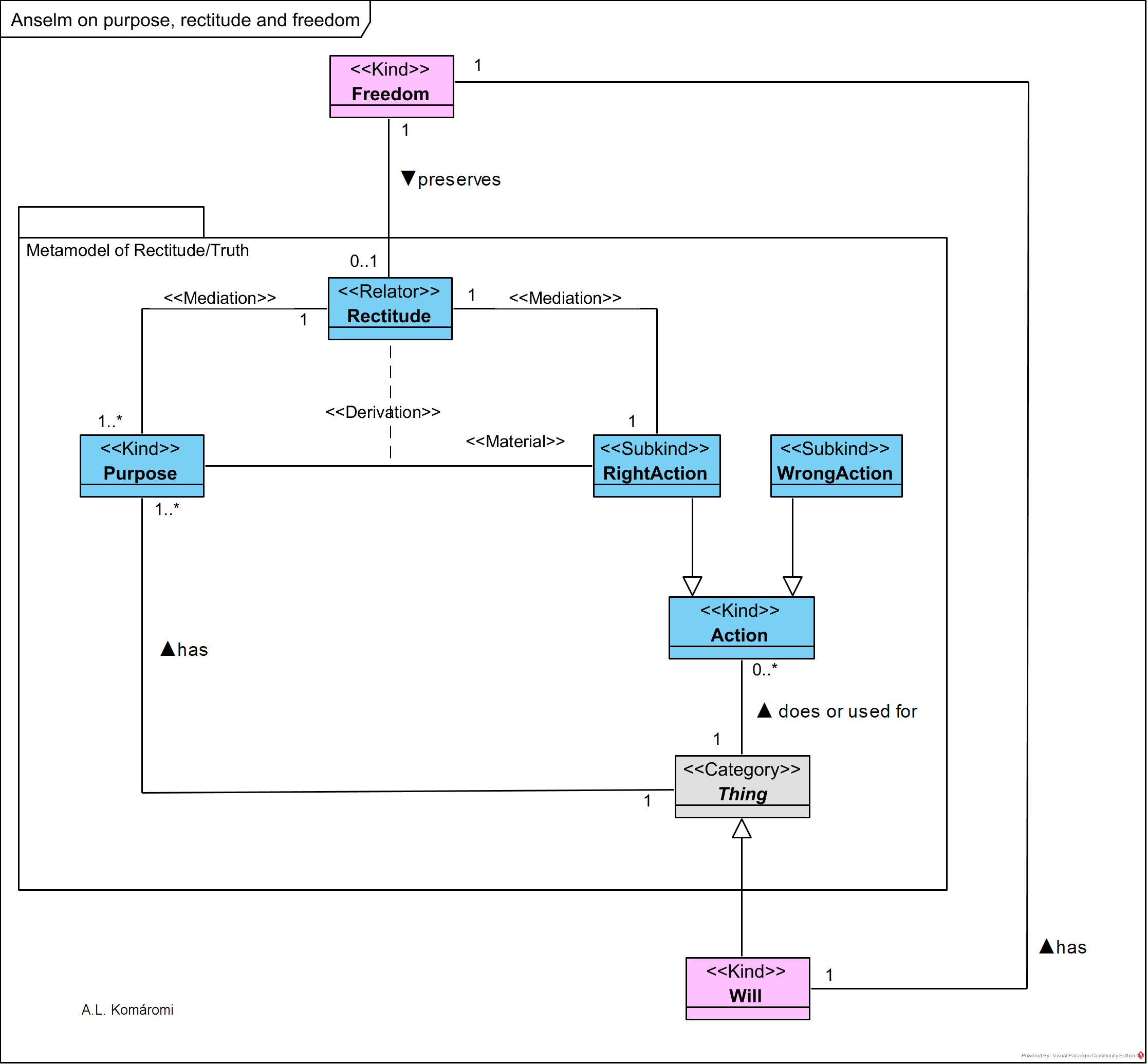

Anselm’s metamodel of rectitude and theory of freedom of will is pictured in the following OntoUML diagram:

| Class | Details | Relations |

| Thing | Thing | has Purpose; does/is used for Action |

| Purpose | Purpose understood in teleological way (see [1.3.4]): the finality, reason or explanation for something. | |

| Action | Things are able to do, or to be used for different “actions“. | |

| RightAction | Right action is performed when the Thing acts/is used according to its purpose. | is subkind of Action; in material relation with Purpose |

| WrongAction | Right action is performed when the thing acts/is used not according to its purpose. | is subkind of Action |

| Rectitude | Rectitude (or Truth) for Anselm “is understood teleologically; a thing is correct whenever it is or does whatever it ought, or was designed, to be or do.” | relates Purpose with RightAction |

| Will | Will | subkind of Thing; has Freedom |

| Freedom | Anselm defines “freedom as ‘the power to preserve rectitude of will for its own sake,’ the arguments of On Truth imply that freedom is also the capacity for justice and the capacity for moral praiseworthiness. Now it is both necessary and sufficient for justice, and thus for praiseworthiness, that an agent wills what is right, knowing it to be right, because it is right. That an agent wills what is right because it is right entails that he is neither compelled nor bribed to perform the act. Freedom, then, must be neither more nor less than the power to perform acts of that sort. […] God and the good angels cannot sin, but they are still free, because they can (and do) preserve rectitude of will for its own sake. In fact, they are freer than those who can sin: ‘someone who has what is fitting and expedient in such a way that he cannot lose it is freer than someone who has it in such a way that he can lose it and be seduced into what is unfitting and inexpedient’. It obviously follows, as Anselm points out, that freedom of choice neither is nor entails the power to sin; God and the good angels have freedom of choice, but they are incapable of sinning.” | preserves Rectitude |

The following table contains some examples of how Anselm’s rectitude meta-model is working:

| Thing | Purpose | Rectitude | RightAction | WrongAction | Explanation |

| statement | signifies that what-is is | truth | signifies that what-is is | — | “statements are made for the purpose of ‘signifying that what-is is’. A statement therefore is correct (has rectitude) when, and only when, it signifies that what-is is. So Anselm holds a correspondence theory of truth, but it is a somewhat unusual correspondence theory. Statements are true when they correspond to reality, but only because corresponding to reality is what statements are for. That is, statements (like anything else) are true when they do what they were designed to do; and what they were designed to do, as it happens, is to correspond to reality.” |

| will | to will: ● justice ● moral evaluation | Rectitude of will | willing what one ought to will | — | “Rectitude of will means willing what one ought to will or (in other words) willing that for the sake of which one was given a will. So, […] the truth or rectitude of a will is the will’s doing what wills were made to do. In De veritate Anselm connects rectitude of will to both justice and moral evaluation.” The will of God and the angels is allways in the state of rectitude. |

| will | to will: ● justice ● moral evaluation | — | — | will for happiness | “In On the Fall of the Devil (De casu diaboli) Anselm extends his account of freedom and sin by discussing the first sin of the angels. In order for the angels to have the power to preserve rectitude of will for its own sake, they had to have both a will for justice and a will for happiness. If God had given them only a will for happiness, they would have been necessitated to will whatever they thought would make them happy. Their willing of happiness would have had its ultimate origin in God and not in the angels themselves. So they would not have had the power for self-initiated action, which means that they would not have had free choice. The same thing would have been true, mutatis mutandis, if God had given them only the will for justice. Since God gave them both wills, however, they had the power for self-initiated action. Whether they chose to subject their wills for happiness to the demands of justice or to ignore the demands of justice in the interest of happiness, that choice had its ultimate origin in the angels; it was not received from God. The rebel angels chose to abandon justice in an attempt to gain happiness for themselves, whereas the good angels chose to persevere in justice even if it meant less happiness. God punished the rebel angels by taking away their happiness; he rewarded the good angels by granting them all the happiness they could possibly want. For this reason, the good angels are no longer able to sin. Since there is no further happiness left for them to will, their will for happiness can no longer entice them to overstep the bounds of justice. Thus Anselm finally explains what it is that perfects free choice so that it becomes unable to sin. […] Like the fallen angels, the first human beings willed happiness in preference to justice. By doing so they abandoned the will for justice and became unable to will justice for its own sake. Apart from divine grace, then, fallen human beings cannot help but sin. Anselm claims that we are still free, because we continue to be such that if we had rectitude of will, we could preserve it for its own sake; but we cannot exercise our freedom, since we no longer have the rectitude of will to preserve. (Whether fallen human beings also retain the power for self-initiated action apart from divine grace is a tricky question, and one I do not propose to answer here.) So the restoration of human beings to the justice they were intended to enjoy requires divine grace.” |

Sources

- All citations from: Williams, Thomas, “Saint Anselm”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Adamson, Peter, “204. A Canterbury Tale: Anselm’s Life and Works“, History of Philosophy without any Gaps podcast

First published: 21/05/2020