Bernardino Telesio (1509–1588) “belongs to a group of independent philosophers of the late Renaissance who left the universities in order to develop philosophical and scientific ideas beyond the restrictions of the Aristotelian-scholastic tradition. [… ] Telesio’s vision of the genesis of nature is simple to the point of being archaic, yet at the same time astonishingly modern in the sense that he seems to have been one of the very first defenders of a theory of natural evolution without metaphysical or theological presuppositions.”

- According to Telesio things are characterized by nature

- Things can be of three subkinds: martter, vacuum and force.

- Force can be: heat and cold.

- “The primary activity of warmth [heat] is to move fast and to dilate and rarefy matter, whereas that of cold is to hinder movement and to condense matter.”

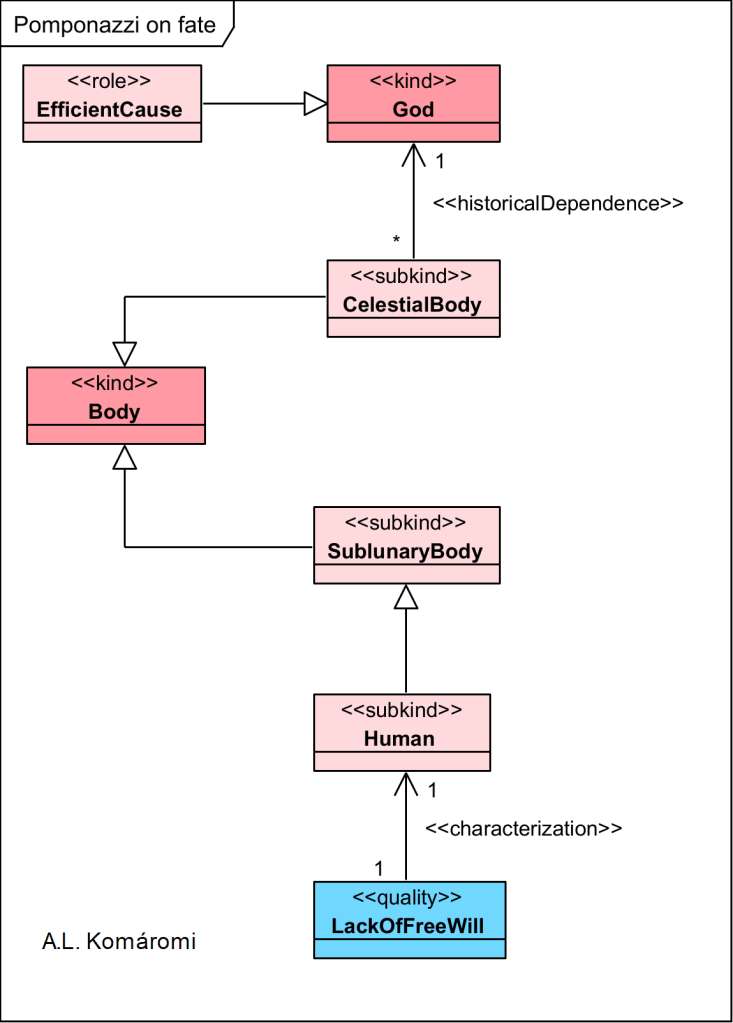

The following OntoUML diagram shows Bernardino Telesio’s model on cosmology:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | All things act solely according to their own nature, starting from the primary forces of cold and heat. The Epicurean chance is enclosed in Telesio’s Stoic-influenced philosophy of nature (Kessler 1992): everything can produce everything, an idea which was soon to be sharply rejected by Francesco Patrizi da Chierso, one of the most important contemporary readers of Telesio (“Obiectiones”, in the appendix of Telesio’s Varii libelli, p. 467 f.). In order to sustain themselves, these primary forces and all beings which arise through their antagonistic interaction must be able to sense themselves as well as the opposite force, that is, they must sense what is convenient and what is inconvenient or damaging for their survival and well-being. Sensation, therefore, is not the property of embodied souls. Telesio’s philosophy can thus be described as a pansensism in the sense that all beings, animate or inanimate, are said to have the power of sensation. | |

| Thing | Telesio’s vision of the genesis of nature is simple to the point of being archaic, yet at the same time astonishingly modern in the sense that he seems to have been one of the very first defenders of a theory of natural evolution without metaphysical or theological presuppositions. According to his De rerum natura, the only things which must be presupposed are passive matter and active force, the latter of which Telesio thought of as twofold, heat and cold. | characterizes Thing |

| Matter | the only things which must be presupposed are passive matter and active force, the latter of which Telesio thought of as twofold, heat and cold | subkind of Thing |

| Vacuum | The existence of vacuum within space is admitted, but things are said to have a natural inclination to avoid empty space. | subkind of Thing |

| Force | the only things which must be presupposed are passive matter and active force, the latter of which Telesio thought of as twofold, heat and cold. | subkind of Thing |

| Heat | the only things which must be presupposed are passive matter and active force, the latter of which Telesio thought of as twofold, heat and cold. | subkind of Force |

| Cold | the only things which must be presupposed are passive matter and active force, the latter of which Telesio thought of as twofold, heat and cold. | subkind of Force |

| Move&Dilate | The primary activity of warmth is to move fast and to dilate and rarefy matter, whereas that of cold is to hinder movement and to condense matter. Things differ according to the amount of heat or cold they possess (and therefore according to their density and derivative qualities such as velocity and colour). The quantity of matter is not changed through the action of these forces upon it. The role of heat, cold and matter as ‘natural principles’ had been highlighted before by Girolamo Fracastoro in the first version of the de natura. | characterizes Heat |

| Hinter& Condense | The primary activity of warmth is to move fast and to dilate and rarefy matter, whereas that of cold is to hinder movement and to condense matter. | characterizes Cold |

Sources

- Boenke, Michaela, “Bernardino Telesio“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

First published: 05/11/2022