John Buridan (Jean Buridan 1301-1358) in Sophismata, Quaestiones in Porphyrii Isagogen and Summulae de Dialectica writes about the mechanism of interpretation and concept formation in languages:

- Meaningful utterances and inscriptions generate understanding in the mind; thus, they belong to a conventional language. Buridan thinks that each inscription and utterance is singular, i.e., if a person pronounces twice the phrase

"Socrates is a man,"that is two utterances, and as such two tokens. - Meaningful utterances and inscriptions are singular tokens. Similar tokens are recognized by the human mind and grouped in token types. E.g., the utterance

"Socrates is a man"and the inscription"Socrates is a human"are similar, and as such they belong to the same token type. - The mind subordinates the token types and the belonging tokens to the mental concept through the interpretation process, characterized by a context, which includes conditions like where, when, by whom, to whom, intention, etc. A mental concept is an act of understanding in a singular mind.

- The mental concept can not vary its semantic features in a given mind. “The same concept always represents the same things in the same way, so there is not even a variation of supposition in mental language in the way there is in spoken or written languages”.

- Conventional interpretations are of proper sense, while otherwise of improper sense. Improper sense interpretation can be ironic, figurative, metaphoric, etc.

- Buridan’s model of language is thoroughly nominalist (see [4.4.1]).

- Buridan thinks, that the concepts form a natural and mental language, which is prior to spoken and written conventional languages, like English, Latin, French, Greek, Hungarian etc. (see [4.0.1])

- (Buridan never used the terms token and token type, however, those entities are present in his model.)

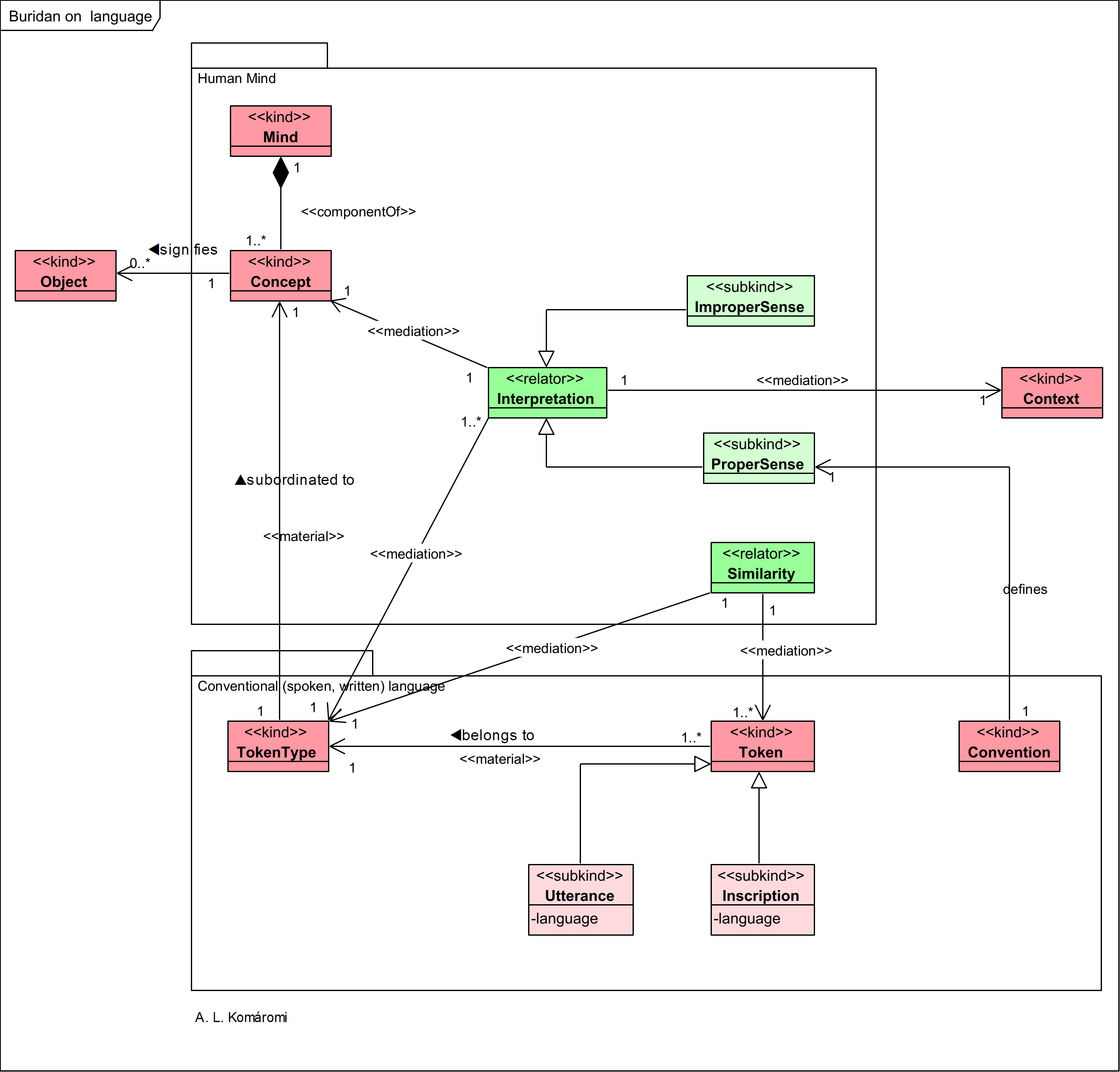

The following OntoUML diagram shows the mechanism of understanding for natural language according to Buridan:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Mind | A human mind. | |

| Concept | “concepts, the acts of understanding which render utterances and inscriptions meaningful, are just as singular as as are the utterances and inscriptions themselves. In addition, the acts of imposition whereby we subordinate utterances and inscriptions to concepts are singular, voluntary acts. This renders the relation of subordination conventional and changeable from one occasion of use to the next. So, the correlation of these singular items, inscriptions, utterances, and concepts is to be established in a piecemeal way, by carefully evaluating which utterance or inscription is subordinated to which concept in whose mind, on which occasion of its use, in what context. […] Buridan makes it quite clear that in his view a concept cannot vary its semantic features, which means that there is no ambiguity in mental language. The same concept always represents the same things in the same way, so there is not even a variation of supposition in mental language in the way there is in spoken or written languages” | component of Mind; signifies Object |

| Object | An object, a thing or state of affairs in the external world. | |

| TokenType | “Individual linguistic signs, symbol tokens, come in types [token types] based on their recognizable similarities. Indeed, even if some tokens are not inherently similar, such as the íupper- and lowercase letters of the alphabet (A, a, B, b, etc.) or different fonts or typefaces (a, a, a, etc.), we are trained early on to recognize them as similar. Obviously, the same applies to utterances at an even earlier stage, in a less formally educational setting, leaving much to our natural abilities to recognize phonemic similarities. Therefore, what primarily allows any sort of uniformity of interpretation is the fact that even if in principle any token of any type can be interpreted ad placitum at any time, tokens are interpreted in types. Once we specify the relevant variable conditions of interpretation, such as when, where, by whom, to whom, according to what intention, and so on a token is to be interpreted, then any token of the same type under the same conditions is to be interpreted in the same way. That is to say, a rule that applies to a token in virtue of its interpretation as belonging to a given type under such and such conditions of its use applies to all tokens of the same type under the same conditions. To be sure, Buridan never talks about tokens or types. This is modern terminology, which I bring in to summarize the gist of Buridan’s ideas.” | subordinated to Concept |

| Token | “Buridan does talk about the fact that any linguistic sign (whether spoken [utterance], written [incription], or even mental) is a singular occurrence (which we call a token). He also talks about the fact that some of these are recognizably similar (thereby constituting what we would call a type), and about the fact that once we fix the variable conditions of interpretation, then talking about one token is equivalent to talking about all.” | belongs to TokenType |

| Similarity | “Individual linguistic signs, symbol tokens, come in types [token types] based on their recognizable similarities. Indeed, even if some tokens are not inherently similar, such as the íupper- and lowercase letters of the alphabet (A, a, B, b, etc.) or different fonts or typefaces (a, a, a, etc.), we are trained early on to recognize them as similar.” | relates TokenType with Token |

| Utterance; Inscription | “[…] any spoken language is but a system of singular utterances [vox], while any written language is but a system of singular inscriptions. Moreover, it is obvious that any such utterance or inscription belongs to a language only insofar as it produces some understanding in the minds of competent users of the language, that is to say, insofar as it is meaningful at all. […] Buridan does talk about the fact that any linguistic sign (whether spoken [utterance], written [incription], or even mental) is a singular occurrence (which we call a token) ” | subtype of Token |

| Interpretation | “That is to say, a rule that applies to a token in virtue of its interpretation as belonging to a given type under such and such conditions of its use applies to all tokens of the same type under the same conditions. […] To be sure, the correct interpretation need not be the interpretation expressing the proper or primary sense, because occasionally the correct, intended interpretation is provided by some improper, secondary sense of the phrase in question. In fact, this is precisely why it is the intention expressed by the phrase on the given occasion of its use that determines its correct semantic evaluation. The reason for this is that the written or spoken phrase has any sense whatsoever only in virtue of the fact that it is subordinated to the concept or intention it is supposed to express according to the intended interpretation, for it signifies just what is conceived by the corresponding concept. So, the correct interpretation of an utterance or inscription is fixed by the mental concept to which the utterance or inscription is actually subordinated on a particular occasion of its use. Consequently, the reason why tokens of the same type have the same semantic features allowing us the primacy of mental language to evaluate them in the same way in the same type of context is that under these circumstances they are subordinated to the same concept. […] So, although we can use any utterance and inscription in the way we wish, once it is conventionally instituted to signify somehow, that established signifcation is to be regarded as its proper, primary sense, and any other only as a secondary, improper sense. Nevertheless, there is no hard and fast rule that says that we should take the expressions of our spoken or written languages always in their primary sense, and that we should evaluate our propositions for their truth or falsity accordingly. On the contrary, sometimes we are obliged to take written or spoken expressions in their secondary, improper sense, if that is what is intended. […] the occurrences of two token-terms of the same type (provided they are interpreted in the same way) are subordinated to numerically one and the same concept in the same mind, and so, given that whatever semantic features they have they have from the semantic features of the concept, no wonder they will have exactly the same semantic features. But then, if the semantic features of concepts are not variable, this certainly suffi ciently fixes the interpretation of token-terms according to a given subordination, for according to that subordination they will all be subordinated” | mediates Concept, Context and TokenType |

| Context | Context is the “variable conditions of interpretation, such as when, where, by whom, to whom, according to what intention, and so on a token is to be interpreted […] So, in the specification of acts of imposition we might use variables indistinctly referring to any number of individual users, various times, places, or any other relevant contextual factors […]” | characterizes Interpretation |

| ProperSense; ImproperSense | “So, although we can use any utterance and inscription in the way we wish, once it is conventionally instituted to signify somehow, that established signifcation is to be regarded as its proper, primary sense, and any other only as a secondary, improper sense.” Improper sense interpretation can be ironic, figurative, metaphoric, etc. | subkinds of Interpretation |

| Convention | “So, although we can use any utterance and inscription in the way we wish, once it is conventionally instituted to signify somehow, that established signification is to be regarded as its proper, primary sense, and any other only as a secondary, improper sense.” Convention might vary in time. | defines ProperSense |

Sources:

- All citations from: Klima, Gyula, “John Buridan”, Oxford University Press, 2009

- Zupko, Jack, “John Buridan“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 14/8/2021

Updated: 20/8/2021