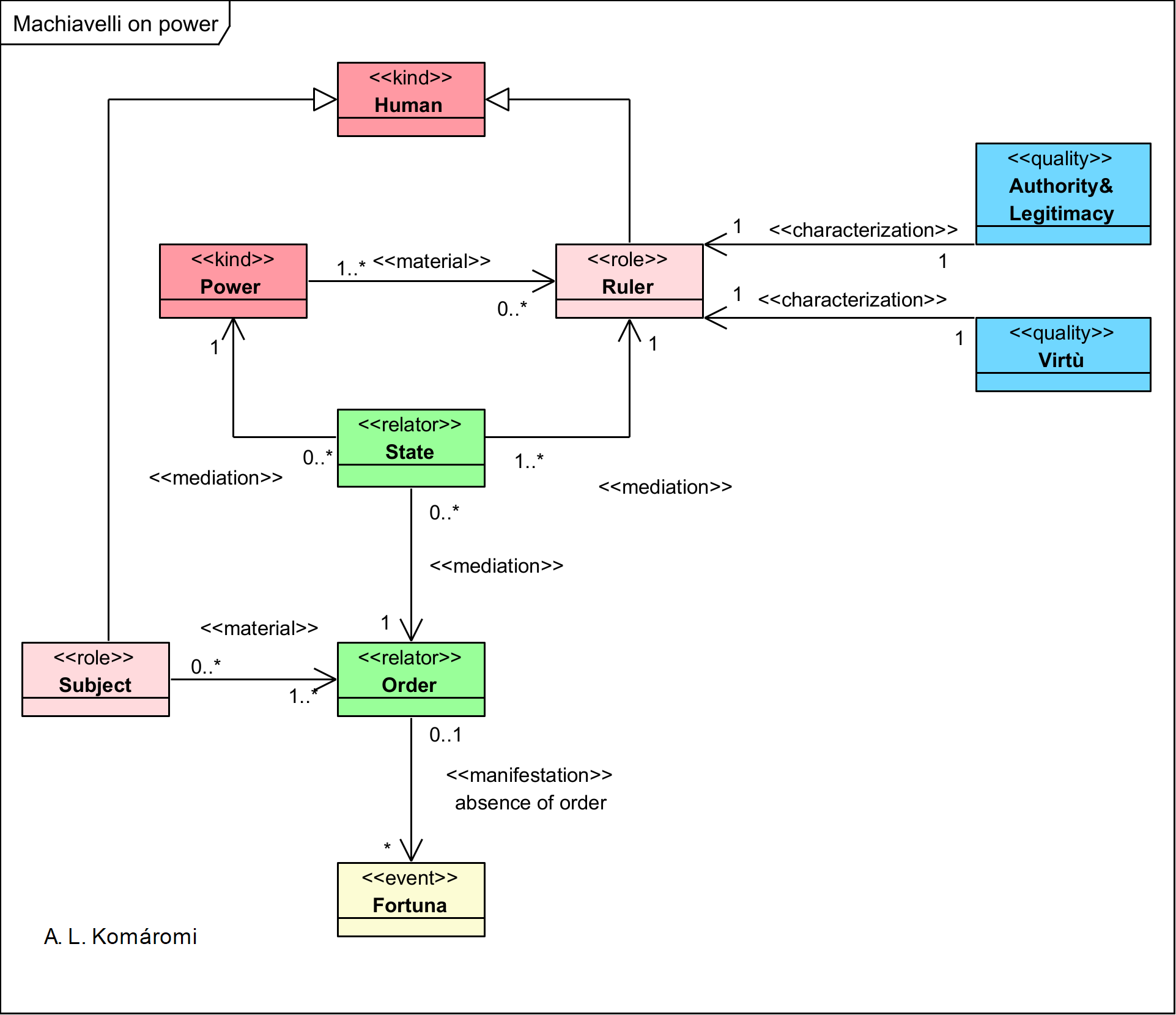

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) The Prince analized power on novel, uncompromising ways. Here are some highlights of his model.

- Humans are can be rulers or subjects.

- A ruler is characterized by legitimacy, authority, and Virtù.

- The state mediates power with the ruler; and the state on the other hand provides order.

- Subject is in material relation with order.

- Fortuna manifests in a lack of order.

The following OntoUML diagram shows the main structure of Machiavelli’s model:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Human | A human person. | |

| Ruler | “For Machiavelli, power characteristically defines political activity, and hence it is necessary for any successful ruler to know how power is to be used.” | role of Human |

| State | “Machiavelli’s “state” remains a personal patrimony, a possession more in line with the medieval conception of dominium as the foundation of rule. (Dominium is a Latin term that may be translated with equal force as “private property” and as “political dominion”.) Thus, the “state” is literally owned by whichever prince happens to have control of it. Moreover, the character of governance is determined by the personal qualities and traits of the ruler—hence, Machiavelli’s emphasis on virtù as indispensable for the prince’s success. These aspects of the deployment of lo stato in The Prince mitigate against the “modernity” of his idea. Machiavelli is at best a transitional figure in the process by which the language of the state emerged in early modern Europe, as Mansfield concludes.” | mediates Power with Ruler |

| Power | “For Machiavelli, there is no moral basis on which to judge the difference between legitimate and illegitimate uses of power. Rather, authority and power are essentially coequal: whoever has power has the right to command; but goodness does not ensure power and the good person has no more authority by virtue of being good. […] For Machiavelli, power characteristically defines political activity, and hence it is necessary for any successful ruler to know how power is to be used. Only by means of the proper application of power, Machiavelli believes, can individuals be brought to obey and will the ruler be able to maintain the state in safety and security. […] Thus, in direct opposition to a moralistic theory of politics, Machiavelli says that the only real concern of the political ruler is the acquisition and maintenance of power (although he talks less about power per se than about “maintaining the state”.) In this sense, Machiavelli presents a trenchant criticism of the concept of authority by arguing that the notion of legitimate rights of rulership adds nothing to the actual possession of power.” | |

| Order | The Discourses certainly draw upon the same reservoir of language and concepts that flowed into The Prince, but the former treatise leads us to draw conclusions quite different from—many scholars have said contradictory to—the latter. In particular, across the two works, Machiavelli consistently and clearly distinguishes between a minimal and a full conception of “political” or “civil” order, and thus constructs a hierarchy of ends within his general account of communal life. A minimal constitutional order is one in which subjects live securely (vivere sicuro), ruled by a strong government which holds in check the aspirations of both nobility and people, but is in turn balanced by other legal and institutional mechanisms. In a fully constitutional regime, however, the goal of the political order is the freedom of the community (vivere libero), created by the active participation of, and contention between, the nobility and the people. As Quentin Skinner (2002, 189–212) has argued, liberty forms a value that anchors Machiavelli’s political theory and guides his evaluations of the worthiness of different types of regimes. Only in a republic, for which Machiavelli expresses a distinct preference, may this goal be attained. | relates with state |

| Subject | A minimal constitutional order is one in which subjects live securely (vivere sicuro), ruled by a strong government [state] which holds in check the aspirations of both nobility and people, but is in turn balanced by other legal and institutional mechanisms. | subkind of Human |

| Authority&Legitimacy | Machiavelli’s political theory, then, represents a concerted effort to exclude issues of authority and legitimacy from consideration in the discussion of political decision-making and political judgment. Nowhere does this come out more clearly than in his treatment of the relationship between law and force. Machiavelli acknowledges that good laws and good arms constitute the dual foundations of a well-ordered political system. But he immediately adds that since coercion creates legality, he will concentrate his attention on force. He says, “Since there cannot be good laws without good arms, I will not consider laws but speak of arms” (Prince CW 47). In other words, the legitimacy of law rests entirely upon the threat of coercive force; authority is impossible for Machiavelli as a right apart from the power to enforce it. Consequently, Machiavelli is led to conclude that fear is always preferable to affection in subjects, just as violence and deception are superior to legality in effectively controlling them. Machiavelli observes that one can say this in general of men: they are ungrateful, disloyal, insincere and deceitful, timid of danger and avid of profit…. Love is a bond of obligation which these miserable creatures break whenever it suits them to do so; but fear holds them fast by a dread of punishment that never passes. (Prince CW 62; translation revised) | characterizes Ruler |

| Virtù | “The term that best captures Machiavelli’s vision of the requirements of power politics is virtù. While the Italian word would normally be translated into English as “virtue”, and would ordinarily convey the conventional connotation of moral goodness, Machiavelli obviously means something very different when he refers to the virtù of the prince. In particular, Machiavelli employs the concept of virtù to refer to the range of personal qualities that the prince will find it necessary to acquire in order to “maintain his state” and to “achieve great things”, the two standard markers of power for him. This makes it brutally clear there can be no equivalence between the conventional virtues and Machiavellian virtù. Machiavelli’s sense of what it is to be a person of virtù can thus be summarized by his recommendation that the prince above all else must possess a “flexible disposition”. That ruler is best suited for office, on Machiavelli’s account, who is capable of varying her/his conduct from good to evil and back again “as fortune and circumstances dictate” (Prince CW 66; see Nederman and Bogiaris 2018). Not coincidentally, Machiavelli also uses the term virtù in his book The Art of War in order to describe the strategic prowess of the general who adapts to different battlefield conditions as the situation dictates. Machiavelli sees politics to be a sort of a battlefield on a different scale.” | characterizes Ruler |

| Fortuna | What is the conceptual link between virtù and the effective exercise of power for Machiavelli? The answer lies with another central Machiavellian concept, Fortuna (usually translated as “fortune”). Fortuna is the enemy of political order, the ultimate threat to the safety and security of the state. Machiavelli’s use of the concept has been widely debated without a very satisfactory resolution. Suffice it to say that, as with virtù, Fortuna is employed by him in a distinctive way. Where conventional representations treated Fortuna as a mostly benign, if fickle, goddess, who is the source of human goods as well as evils, Machiavelli’s fortune is a malevolent and uncompromising fount of human misery, affliction, and disaster. While human Fortuna may be responsible for such success as human beings achieve, no man can act effectively when directly opposed by the goddess (Discourses CW 407–408). | manifests in Fortuna |

Sources

- Nederman, Cary, “Niccolò Machiavelli“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2022 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

First published: 13/10/2022