St Agustine’s (354-430 AD) City of God (De civitate dei) is not a political treatise, however elaborates on some political issues. Here he describes the human community with a methaphor of two cities, which co-exist in the earthly realm, the city of God and the earthly city:

- The city of God is the eternal community of humans with true love (caritas, love of God). This is not to be equated with the institutional church.

- The earthly city is the temporary community of the humans with wrong love (cupidity)

- The two cities co-exist and are intermingled in the frame of the political state, which is a punishment for the fallen man, but also has the role in upholding relative justice.

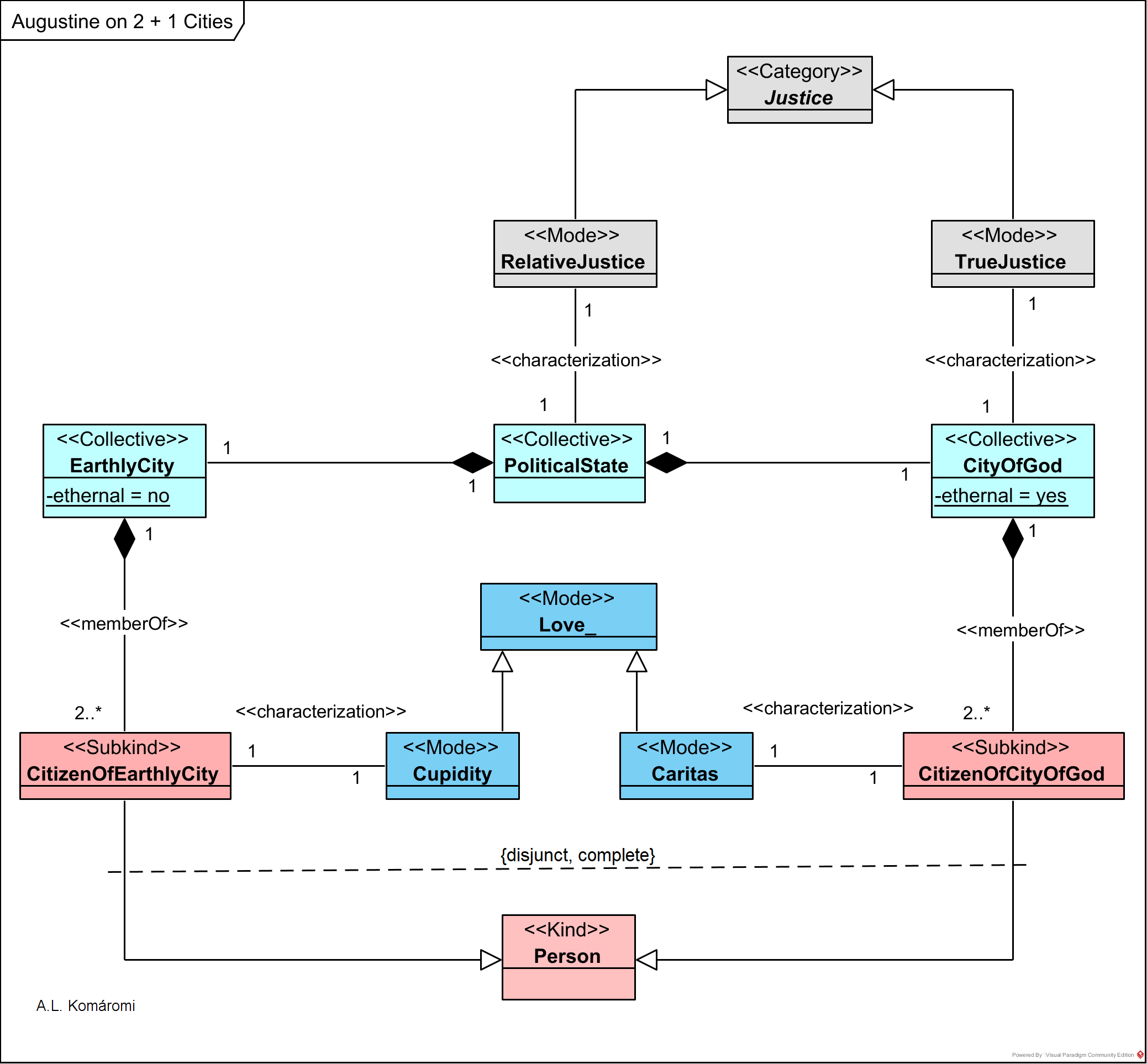

The OntoUML diagram below presents the main components of Augustine’s view on the earthly city, the city of God and the political state:

| Class | Description | Relations |

| EarthlyCity | The earthly city is a metaphor for the community of the persons with the wrong kind of love (love of self, of power, etc.). This community is temporary. | is part of the PoliticalState |

| CityOfGod | The city of God is a metaphor for the community of the persons with the right love (love of God). This community is eternal. | is part of the PoliticalState |

| PoliticalState | Because the citizens of the earthly city and of the city of God live intermingled, the two cities are also intermingled, and are the two parts of the political state, which “is a divinely ordained punishment for fallen man, with its armies, its power to command, coerce, punish, and even put to death, as well as its institutions such as slavery and private property. God shapes the ultimate ends of man’s existence through it. The state simultaneously serves the divine purposes of chastening the wicked and refining the righteous. Also simultaneously, the state constitutes a sort of remedy for the effects of the Fall, in that it serves to maintain such modicum of peace and order as it is possible for fallen man to enjoy in the present world.” | |

| Justice | Justice can be true or relative. | |

| TrueJustice | True justice, according to Augustine, “is love serving God only, and therefore ruling well all else.” | TrueJustice characterizes CityOfGod |

| RelativeJustice | “No earthly [political] state can claim to possess true justice, but only some relative justice by which one state is more just than another. Likewise, the legitimacy of any earthly political regime can be understood only in relative terms: The emperor and the pirate have equally legitimate domains if they are equally just.” (Mattox) | RelativeJustice characterizes EarthlyCity |

| Person | A human person living its earthly or eternal life, who “was brought into existence to endure eternally. Damnation is the just desert of all men because of the Fall of Adam, who, having been created with free will, chose to disrupt the perfectly good order established by God. As the result of Adam’s Fall, all human beings are heirs to the effects of Adam’s original sin, and all are vessels of pride, avarice, greed and self-interest.” (Mattox) | |

| CitizenOfEarthlyCity | A Citizen of the Earthly City is characterized by: “wrong love. A person belongs to […] the earthly city or city of the devil if and only if he postpones love of God for self-love, proudly making himself his greatest good (De civitate dei 14.28). (Mendelson) | is subkind of Person; member of the EarthlyCity |

| CitizenOfCityOfGod | A Citizen of the City of God is characterized by: “right or […] love. A person belongs to the city of God if and only if he directs his love towards God even at the expense of self-love” (Mendelson). They are “pilgrims and foreigners”. | is subkind of Person; member of the CityOfGod |

| Love | “Love is a crucial and overarching notion in Augustine’s ethics. It is closely related to virtue and often used synonymously with will […] or intention (intentio). […] love is a force in our souls that attracts us to the true beauty we find nowhere else but in and above ourselves; it drives us to ascend from the sensible to the intelligible world and to the cognition and contemplation of God […].” (Mendelson) | |

| Caritas | “love means the overall direction of our will (positively) toward God or (negatively) toward ourselves or corporeal creature (De civitate dei 14.7; […]). The former is called love in a good sense (caritas), the latter cupidity or concupiscence (cupiditas), i.e., misdirected and sinful love (De doctrina christiana 3.16).”(Mendelson) | is Love; characterizes CitizenOfCityOfGod |

| Cupidity | “love means the overall direction of our will (positively) toward God or (negatively) toward ourselves or corporeal creature (De civitate dei 14.7; […]). The former is called love in a good sense (caritas), the latter cupidity or concupiscence (cupiditas), i.e., misdirected and sinful love (De doctrina christiana 3.16).” (Mendelson) | is Love; characterizes CitizenOfEarthlyCity |

Sources

- Mendelson, Michael, “Saint Augustine“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Mattox, J. Mark, “Augustine: Political and Social Philosophy”, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

First published: 23/1/2020