Ibn Rushd (Averroes 1126 – 1198) was a prolific commentator of Aristotle’s works. He wrote a Short, a Medium, and a Long Commentary on De Anima. On its Long Commentary he presented a model of the human soul, where the Material Intellect is posited as a unique function shared and used by all humans, where:

- The model is inspired from Aristotle (see [1.3.6]), Al-Farabi (see [3.2.2]) and Ibn Sina (see [3.3.3]).

- The different functions of the human soul are linked to the human body, so the individual, particular soul does not survive the death of the body.

- The Material Intellect is single, linked to an immortal substance different from the human body, and is shared and commonly used by all humans. The uniqueness of the material intellect assures the unity of the Universals (e.g., that all humans have the same concepts about numbers), the immortal substance assures its immortality.

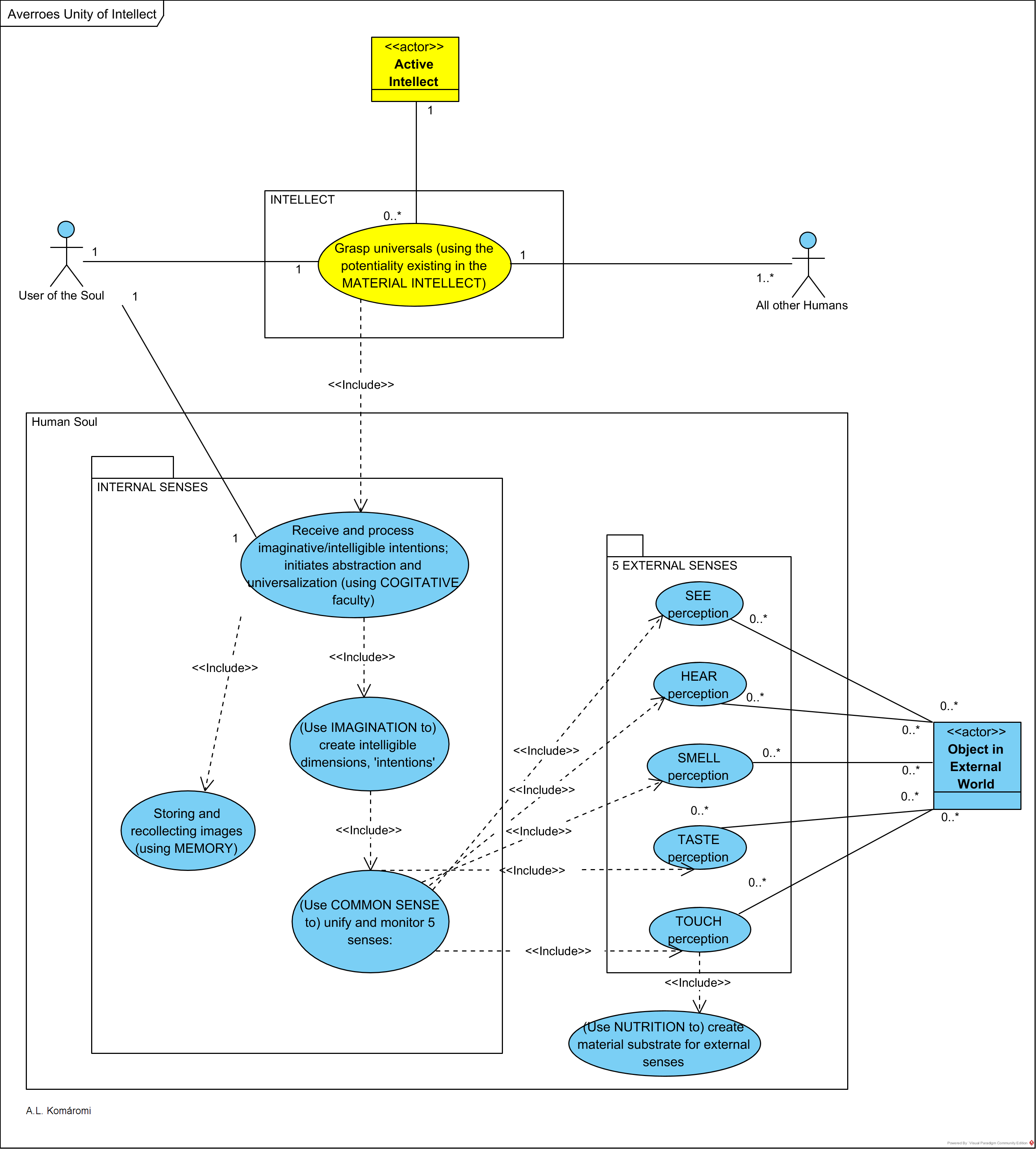

The following UML Use Case diagram presents Ibn Rushd’s view on the human soul:

| Faculty | Related Use Case |

| NUTRITION | (Use NUTRITION to) create material substrate for external senses: “Averroes stresses the hierarchical structure of the soul, beginning with the nutritive faculty. It serves as a substrate for the sensory faculties, their matter ‘disposed’ to receive sensory perceptions.” (Ivry) |

| EXTERNAL SENSES | Use TASTE, TOUCH, SMELL, HEAR, SEE perception: “The form of an external object is sensed at first with its many ‘rinds’ or husks of corporeality (qushûr), for which read particularity.”(Ivry) |

| COMMON SENSE (internal sense) | (Use COMMON SENSE to) unify and monitor 5 senses: “common sense […] receive (intentional adaptations of) [forms of external objects by transmitted by external senses] in an increasingly immaterial manner”(Ivry) |

| MEMORY | Storing and recollecting images (using MEMORY): Memory stores […] dismembered essentialized images and is able to remember them at will, that is, with an act of will. Recollection (tadhakkur) rejoins them in the cogitative faculty with full images that flesh out the corporeal features of the sought object.[…] While generally restricting the memorative faculty to the intentions of a given imagined form, Averroes acknowledges that it also relates to universals. This is done through the cogitative faculty, associating the universal with some particular image, recollected with the assistance of the intention stored in the memorative faculty; an “intention” that is the distinctive character or nature of that image.[53] That is to say, one remembers a universal idea by remembering an image that connotes it. As Aristotle says, “without an image, thinking is impossible.”(Ivry) |

| IMAGINATION (internal sense) | Use IMAGINATION to) create intelligible dimensions, ‘intentions’: “the senses serve as substrate for the common sense, it the substrate for the imagination, and that faculty the substrate for the rational faculty. As such, the imagination follows the senses in providing the intellect with images that have intelligible dimensions, or “intentions” (ma‘ânî), which term Averroes uses more broadly than heretofore. These intentions are present in the form presented to the senses, but must wait upon an intellect to appreciate them, being represented first as sensible and then imaginative intentions to the senses and imagination, respectively. Averroes thus employs ‘intentions’ to convey not the form of the perceptible object as it is, but as it is sensed, imagined, remembered or intellected by the respective faculties of the soul.” (Ivry) |

| COGITATIVE | Receive and process imaginative/intelligible intentions; initiates abstraction and universalization (using COGITATIVE faculty): “Followed by a ‘discriminating faculty,’ i.e., the cogitative faculty, treated as another internal sense. This faculty actually serves as a bridge between imagination and intellect, dealing with particular images as it does, but selecting out the most distinctive aspect of each percept […]. To that purpose, he enlarges the role of cogitation (fikr) in the cognitive process. As mentioned above, he sees it as a corporeal faculty located in the brain that is able to receive and process both the imaginative intentions found in sensation, and the intelligible intentions of the imagination, thereby initiating the process of abstraction and universalization that the material and Agent intellects complete.” |

| MATERIAL INTELLECT | Grasp universals (using the potentiality existing in the MATERIAL INTELLECT): “In the Long Commentary, Averroes retains the separate, i.e., immaterial yet substantial nature of the material and Agent [Active] intellects, and their relation of potential to actual intelligibility. However, he treats them as two separate substances, not two aspects of the same intelligence. The material intellect is thus hypostatized, treated as a ‘fourth kind of being,’ the celestial principle of matter qua potentiality that, together with the formal principle represented by the Agent [Active] Intellect, explains the nature and activity of intelligible forms; even as sensible objects are constituted by similar hylomorphic principles. The Long Commentary thus sees the material intellect as ‘the last of the separate intellects in the (celestial) hierarchy,’ following the Agent [Active] Intellect (see [3.3.2]). This physical relocation of the material intellect may guarantee its incorruptibility and objectivity, for Averroes, but it does not explain the presence in human beings of a rational faculty, a presence that Averroes recognizes. […] He has indicated that the material or potential intellect is a single, incorporeal, eternal substance shared by the entire human species.” (Davidson) |

Sources

- Ivry, Alfred, “Arabic and Islamic Psychology and Philosophy of Mind”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Herbert A. Davidson, “Alfarabi, Avicenna, and Averroes, on Intellect”, Oxford University Press 1992

- H. Chad Hillier, Ibn Rushd (Averroes) (1126—1198),

- Adamson, Peter, “151 – Single Minded: Averroes on the Intellect”, History of Philosophy without any Gaps podcast

First published: 19/03/2020