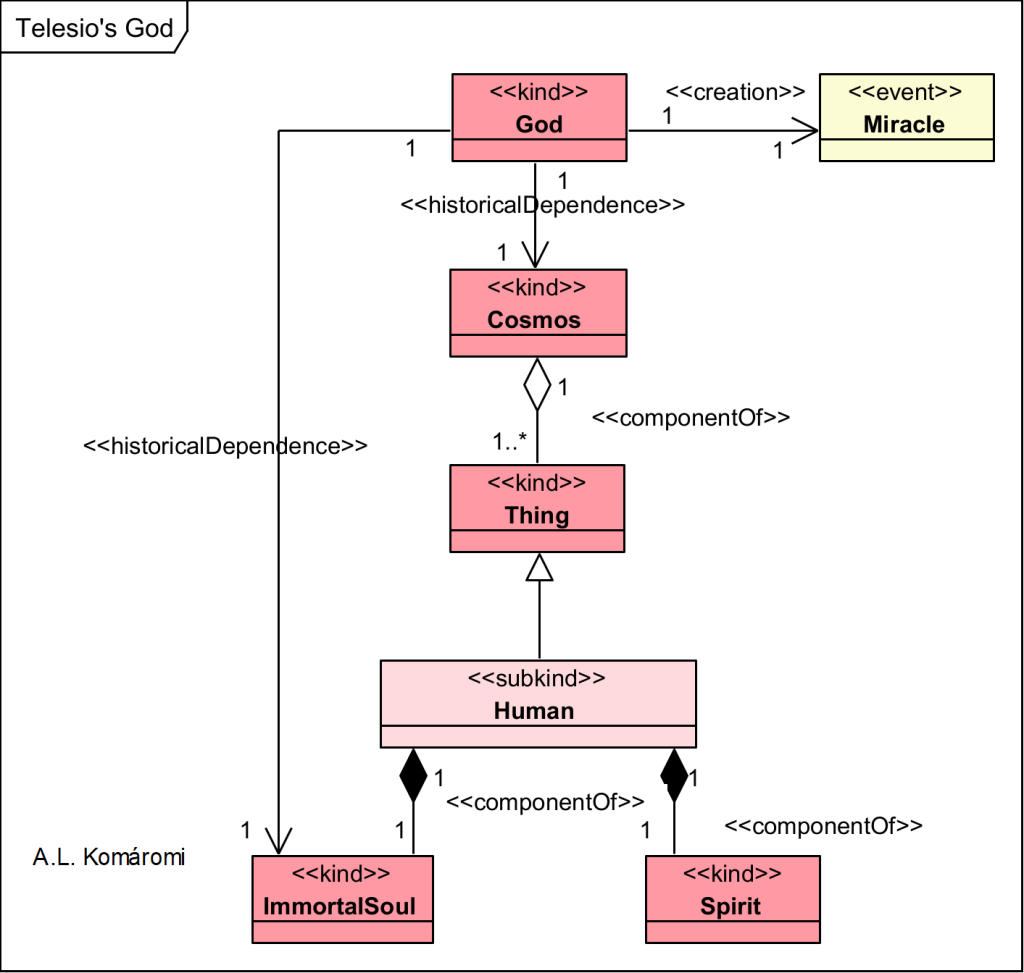

Tommaso Campanella (Stilo, 1568–Paris, 1639) was one of the most important philosophers of the late Renaissance. He was a follower of Bernardino Telesio on cosmology.

- The World historically depends on God.

- The World is component of space.

- Space is a component of matter.

- Matter is component of the body.

- Matter is “but rather as an inert corporeal mass, dark and entirely formless but capable of receiving any form.”

- Body is characterized by heat and cold.

- Heaven and Earth are subkinds of the body.

The following OntoUML diagram depicts Campanella’s model of Natural Philosophy.

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| God | “Campanella begins the “Physiologia” by stating that when the first Being [God]—most powerful, most wise and best—decided to create the world, defined as its “effigy” and the “image” of its infinite goods, it unfolded an “almost infinite” space in which that effigy was placed. This occurred at the outset of that enduring vicissitude of things that we call time and that is the image of eternity from which it flows.” | historicalDependence on |

| World | “From their conflict, deriving from the fact that each wants to take possession of and occupy the greatest possible quantity of matter, come the two primary bodies and elements of the world: the heavens, that are extremely hot, subtle and mobile, since they are formed of matter transformed by heat; and the earth, composed of matter made immobile, dark and dense by cold.” | |

| Space | “Space is defined as “a primary substance or seat or immobile and incorporeal capacity, able to receive any body.” It is homogeneous: human terms such as “high” and “low”, “behind and in front of”, “right” and “left”, refer to bodies that are placed within it; and if the world did not exist, we would imagine space to be empty. In reality, however, it desires fullness, is endowed with attractive force and abhors remaining empty. Bodies, in turn, enjoy mutual contact and hate the void that separates them (Physiologia, in Opera latina, II, pp. 575–77).” | componentOf World |

| Matter | “Within space God places matter that in clear contrast to the conception of Aristotle and Averroes, who defined it as privation and as a pure ens rationis, is regarded by Campanella as a physical entity, deprived of form, shape and action, but capable of being extended, divided, united and of assuming any shape, just as wax can receive an impression from any seal. […] According to Telesio, all being derived from modifications resulting from the actions of the two principles of hot and cold on matter, which he did not regard as an abstract ens rationis (an entity existing in the mind) but rather as an inert corporeal mass, dark and entirely formless but capable of receiving any form.” | componentOf Body |

| Body | “a primary substance or seat or immobile and incorporeal capacity, able to receive any body. […] Bodies, in turn, enjoy mutual contact and hate the void that separates them” | |

| Heaven; Earth | “From their conflict, deriving from the fact that each wants to take possession of and occupy the greatest possible quantity of matter, come the two primary bodies and elements of the world: the heavens, that are extremely hot, subtle and mobile, since they are formed of matter transformed by heat; and the earth, composed of matter made immobile, dark and dense by cold. The clash between the heavens and the earth, between heat and coldness—instruments and ‘craftsmen’ that God uses to produce the infinite modes of his creative wisdom in the wondrous effigy that is the world—gives birth to all individual entities. “ | subkind of Body |

| Heat | “Into this corporeal mass God inserts heat and coldness, the two active principles, that are self-disseminating and incorporeal but can only subsist in bodies. From their conflict, deriving from the fact that each wants to take possession of and occupy the greatest possible quantity of matter, come the two primary bodies and elements of the world: the heavens, that are extremely hot, subtle and mobile, since they are formed of matter transformed by heat; and the earth, composed of matter made immobile, dark and dense by cold.” | characterizes Body |

| Cold | “Campanella’s argument, the constructive element consisted of defending the doctrines of Telesio’s philosophy. According to Telesio, all being derived from modifications resulting from the actions of the two principles of hot and cold on matter […]“ | characterizes Body |

| Inert; Dark; Formless; | “Matter is “but rather as an inert corporeal mass, dark and entirely formless but capable of receiving any form.“ | characterizes Matter |

Sources

- Ernst, Germana and Jean-Paul De Lucca, “Tommaso Campanella“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 27/12/2022