The humanist Lorenzo Valla (c. 1406–1457) in Books II and III of his Repastinatio:

- The most influential classical logical system was elaborated by Aristotle (384-322 BC) in his work Organon (see [1.3.9]) by Aristotle. His theory is centered around the concept of a syllogism (deduction)

- Lorenzo Valla thinks that a main tenet of syllogisms is their artificiality.

- More than that, there are “deviant syllogisms.”

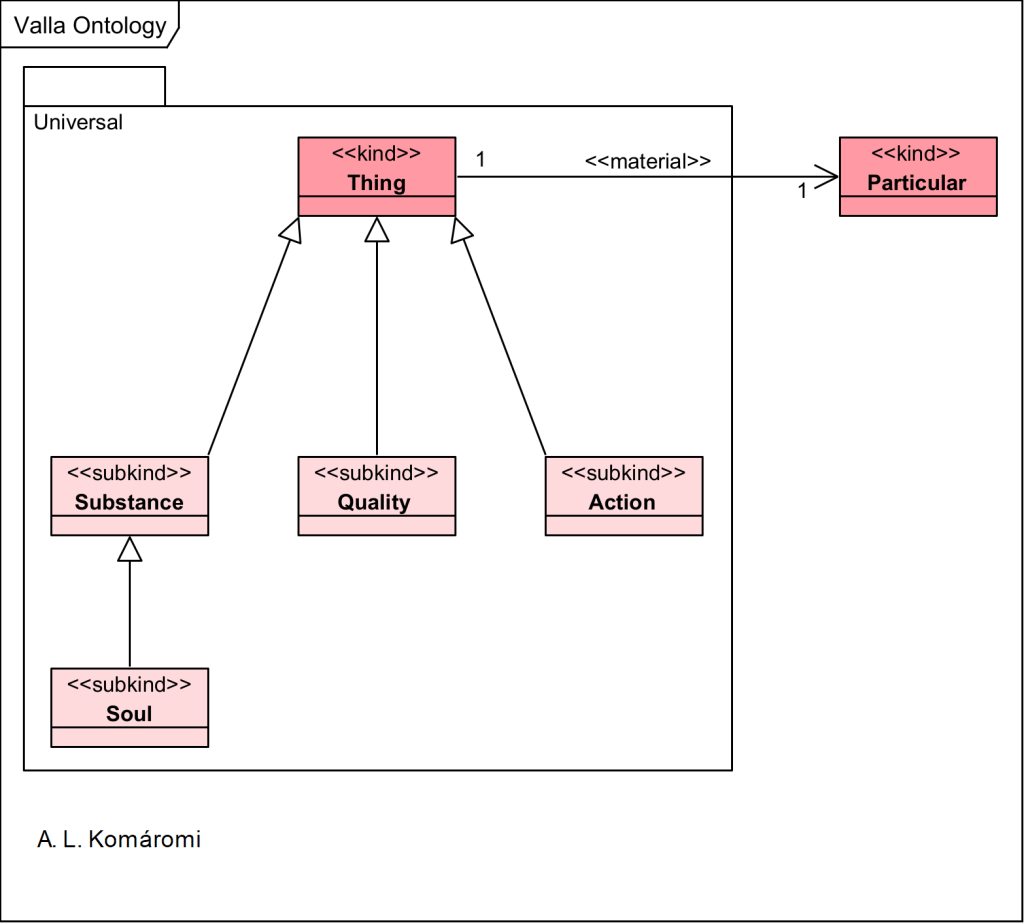

The following OntoUML diagram shows the main classes in this model:

| Class | Description | Relations |

|---|---|---|

| Assertion | Assertions (apophanseis) are sentences with a specific structure “every such sentence must have the same structure: it must contain a subject and a predicate and must either affirm or deny the predicate of the subject.” (Smith) | Subject and Predicate are components of an Assertion |

| Premise | A possible role of an Assertion, relative to a Syllogism is Premise (protasis) | role of Assertion; relates to Conclusion with deduction; has Extreme and MiddleTerm |

| Conclusion | A possible role of an Assertion, relative to a Syllogism is Conclusion (sumperasma) | role of Assertion |

| DeviantSyllogism | “While he does not question the validity of these four moods, he believes that there are many deviant syllogisms that are also valid, for instance: God is in every place; Tartarus is a place; therefore, God is in Tartarus. Here the “every” or “all” sign is added to the predicate in the major proposition. He says, moreover, that an entirely singular syllogism can be valid: Homer is the greatest of poets; this man is the greatest of poets; therefore, this man is Homer. And he gives many other examples of such deviant schemes. Valla thus deliberately ignores the criteria employed by Aristotle and his commentators—that at least one premise must be universal, and at least one premise must be affirmative, and that if the conclusion is to be negative, one premise must be negative—or, at any rate, he thinks that they unnecessarily restrict the number of possible valid figures.” (Nauta) | subkind of Syllogism |

| Artificial | “Without rejecting the syllogism tout court, Valla is scathing about its usefulness. He regards it as an artificial type of reasoning” (Nauta) | |

| Syllogism | “Without rejecting the syllogism tout court, Valla is scathing about its usefulness. He regards it as an artificial type of reasoning, unfit to be employed by orators since it is does not reflect the natural way of speaking and arguing. What is the use, for example, of concluding that Socrates is an animal if one has already stated that every man is an animal and that Socrates is a man? It is a simple, puerile, and pedantic affair, hardly amounting to a real ars (art). Valla’s treatment of the syllogism clearly shows his oratorical perspective. […] One of the two premises contains what is to be proven (que probatur), and the other offers the proof (que probat), while the conclusion gives the result of the proof—into which the proof “goes down” (in quam probatio descendit). It is not always necessary, therefore, to have a fixed order (major, minor, conclusion). If it suits the occasion better, we can just as well begin with the minor, or even with the conclusion. The order is merely a matter of convention and custom (Repastinatio, 1:282–286; 2:531–534; DD 2:216–39). These complaints about the artificiality of the syllogism inform Valla’s discussion of the three figures of the syllogism. Aristotle had proven the validity of the moods of Figure 2 and 3 by converting them to four moods of Figure 1; and this was taught, for example, by Peter of Spain (thirteenth century) in his widely read handbook on logic, the Summulae logicales, certainly consulted by Valla here. Valla regards this whole business of converting terms and transposing propositions in order to reduce a particular syllogism to one of these four moods of Figure 1 as useless and absurd” (Nauta) | Syllogism relates 2 Premises with 1 Conclusion |

| Mood | “These complaints about the artificiality of the syllogism inform Valla’s discussion of the three figures of the syllogism. Aristotle had proven the validity of the moods of Figure 2 and 3 by converting them to four moods of Figure 1; and this was taught, for example, by Peter of Spain (thirteenth century) in his widely read handbook on logic, the Summulae logicales, certainly consulted by Valla here. Valla regards this whole business of converting terms and transposing propositions in order to reduce a particular syllogism to one of these four moods of Figure 1 as useless and absurd.” (Nauta) | Mood characterizes Syllogism; has Proof |

| Proof | “Following Quintilian, he stresses that the nature of syllogistic reasoning is to establish proof.” (Nauta) |

Sources

- Nauta, Lodi, “Lorenzo Valla”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- C, Robin, “Aristotle’s Logic”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

First published: 15/9/2022